La préoccupation climatique serait juste une manifestation égoïste de mauvaise conscience des pays riches, ne tenant aucun compte d’une aspiration légitime au “développement” des pays pauvres, qui veulent émettre de plus en plus de gaz à effet de serre. Et qu’en pensent les intéressés, ou du moins certains d’entre eux ? Voici un papier (long et en Anglais, pardon pour les non anglicistes et les gens pressés) de Anil AGARWAL. Sa position en étonnera plus d’un !

Anil Agarwal était le fondateur et directeur du Center for Science and the Environment à Delhi.

I – The Nature of the Challenge

The ongoing negotiations to develop an international regime to deal with the problem of global warming and the associated climate change – possibly the biggest environmental challenge facing humanity – is throwing up a minefield of different interests which have to be resolved if a framework of international cooperation has to be developed in which all nations of the world have equal confidence.

The nations of the world are essentially confronted with the following three critical questions:

1. What actions are needed in order to prevent climate change? This can be called the benchmark of ecological effectiveness for any action plan that emerges. Such a plan must ensure that the build up of greenhouse gases is not only arrested but reduced as fast as possible.

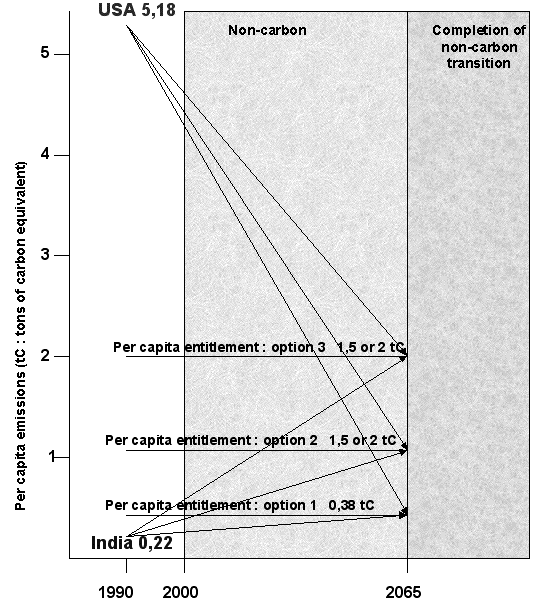

2. How do we equitably share the proposed actions given the two basic facts that there is an enormous disparity in per capita emissions of different nations in the world and, as long as the world remains within a carbon-based energy economy, these emissions are closely related to economic growth and standards of living ? This can be called the benchmark of equity and global solidarity. The inequity in carbon dioxide emissions, as it currently stands, is represented by the fact that one US citizen emitted in 1996 as much as 17 Maldivians, 19 Indians, 30 Pakistanis, 49 Sri Lankans, 107 Bangladeshis, 134 Bhutanese and 269 Nepalis.

| Country | 1990 Per capita emissions (ton equivalent C) | 1996 Per capita emissions (ton equivalent C) | 1990 No. of citizens equivalent to one US citizen | 1996 No. of citizens equivalent to one US citizen |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 5,18 | 5,37 | 1 | 1 |

| Bangladesh | 0,04 | 0,05 | 130 | 107 |

| Bhutan | 0,02 | 0,04 | 259 | 134 |

| India | 0,22 | 0,29 | 24 | 19 |

| Maldives | 0,19 | 0,31 | 27 | 17 |

| Nepal | 0,01 | 0,02 | 518 | 269 |

| Pakistan | 0,16 | 0,18 | 32 | 30 |

| Sri Lanka | 0,06 | 0,11 | 86 | 49 |

Table 1 – Carbon dioxide emissions per capita

Source: Gregg Marland et al 1999, National CO2 Emissions from Fossil Fuel Burning, Cement Manufacture and Gas Flaring, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, USA.

Though the gap is narrowing, this extraordinary inequity makes it very difficult for nations to agree to a common action plan unless there is equity without which global solidarity will not be possible. Since emissions are strongly linked to economic growth and standards of living within a carbon-based energy economy, it will be important to ensure that the poorest people of the world have the maximum ‘environmental space’ for their economic growth in the future.

3. How do we make sure that any action plan that is developed is cost-effective and does not disrupt either the global economy or any individual nation’s economy ? This can be called the benchmark of economic effectiveness. This benchmark is very important for those countries which have high emissions in quantitative terms and will, therefore, have to invest substantially in emissions stabilisation as well as reduction.

It is very clear that unless all the three benchmarks indicated above are appropriately addressed in any proposed action plan to prevent climate change, it is unlikely to be widely accepted by all the nations of the world and inspire worldwide confidence.

As things stand, the benchmark of ecological effectiveness appears to have the greatest advocates in several countries of the European Union, especially those where Green Parties have acquired political importance in recent years.

On the other hand, the issue of equity and global solidarity is of greatest concern to poor countries, including India and China, whose per capita incomes are extremely low and whose people look forward to higher economic levels in the future. And, therefore, they feel the maximum need for ‘environmental space’ for future economic growth.

The third benchmark is of greatest interest to the United States and a few other industrialised countries whose total stock of emissions and, hence, emissions reduction costs are high and who feel that this cost would be quite heavy for their economies to bear.

II – The Impact of Climate Change

While keeping the problem of climate change in mind it is very important to ask ourselves the question who will suffer the most? The simple answer is that it would be the poor nations who will suffer the most and even more so the poor people, who live in these poor nations. This is simply because the poor nations have very few financial and technical resources to deal with the adverse effects of climate change. And poor people live mainly in tropical countries where the changes could be the most adverse.

In November 1998, a few days before the fourth Conference of Parties, some 9.000 people died from an hurricane in Central America. Hurricanes are not uncommon in the Americas but never have so many people died in a hurricane in United States because the US government and the US people have access to far more financial and technical resources to deal with a natural calamity.

Hurricane Mitch

On October 30, 1998, Hurricane Mitch devastated Central America. The lake formed in the cone of the dormant Casita volcano in northwest Nicaragua during days of endless downpour burst through the mountainside releasing a mixture of water, mud, rocks and even trees. It swept away four nearby villages. The 180 miles per hour winds left more than 10,000 people dead. As many as 13,000 people were reported missing. There were a staggering 2.8 million homeless people in Nicaragua, the Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador. Of a total combined population of 11 million in Nicaragua and the Honduras, about 1 million were left shelterless.

More than half of the Honduras was submerged: towns, villages, schools and hospitals were all under water. Deprived

victims had no choice but to migrate to neighbouring nations. This led to a rise in the number of illegal immigrants to the US. US federal agents at the Texas border arrested as many as 6,555 people when they tried to enter the US illegally. This is an increase in 86 per cent from the previous year.

Nicaragua and the Honduras, two of the poorest nations in the hemisphere, were hit the hardest by the aftermath of the

hurricane. Both countries suffered losses equivalent to half of their gross domestic product. The loss in Nicaragua is estimated at US$ 1 billion, while the Honduras suffered approximately US$ 4 billion in damages. The destruction has set back the region’s infrastructural and economic base by at least 20 years.

The Inter-American Development Bank estimated that up to 90 per cent of the roads and other infrastructure in the Honduras were destroyed. Farming, the backbone of the region’s economy, was severely crippled. About 70 per cent of the Honduras’ key crops, including bananas, beans and corn, were destroyed completely.

Experts have blamed the widespread devastation caused by Hurricane Mitch on a combination of the area’s vulnerability to natural disasters like earth tremors and volcanic activities, and the region’s poverty. An analysis of the soils and slopes in Central America show that this disaster was just waiting to happen. In the Honduras alone, it is believed that approximately 9,000 hectares of forest land is lost to deforestation every year. To add to the woes, thousands of landmines buried and still active in Central America may have been dispersed by the mudslides caused by Hurricane Mitch.

Human factors magnified the impact of this natural disaster. The houses were poorly built and located on perilous terrain. The water basins were poorly managed. Drought and deforestation also triggered more mudslides increasing the fury of Hurricane Mitch.

Besides, even before Hurricane Mitch, almost half the population of the Honduras and Nicaragua were below the poverty line and were gradually recovering from the civil strifes of the 1980s. Both these nations are burdened with massive foreign debts. Nicaragua, which has a foreign debt of US$ 6.1 billion, has the highest per capita debt in the world. According to Oxfam, US$ 254 million, or 54 per cent of the government’s revenue, went towards debt-servicing in 1997. This is two and a half times the country’s total expenditure on health and education as it approximately spent 22 per cent. The Honduras is not any better off. It owes US$ 4.1 billion and spent a third of its revenue on paying back its debts in 1997.

Aid packages started flowing in from all parts of the world soon after the disaster. By December 1998, donor countries and agencies contributed nearly US$ 5 billion for redevelopment, which amounts to 12 per cent of the combined gross national product of the four nations. Besides, US$ 1.2 billion came in the form of debt relief and an additional US$ 0.6 billion as emergency aid. Additional aid packages are still expected to arrive.

Sources:

1. Alan Zarembo and Brook Larmer with Debra Rosenberg 1998, The Fury of Mitch, in Newsweek, November 16, pp.32-33.

2. Anon 1998, Hurricane Aid,in USA Today, November 13.

3. Anon 1999, The Americas after Mitch, in The Economist, January-February, p.45.

4. Serge F. Kovaleski 1998, The Anger Beneath Mitch’s Mud, in The Washington Post, November 15.

5. Anon 1998, The Tempest,in Down to Earth, December 15.

6. William Branigin 1998, Debt Cancellation for Honduras and Nicaragua, in The Washington Post, Nov 20.

7. Alan Zarembo 1999, Mitch’s Migrants, in Newsweek, March 1, p.21.

8. Anon 1999, Central American Development at crossroads after Mitch in Development Update, January-February, p.3.

It is important to remember that less than 30 years ago, a new country called Bangladesh was created because of a cyclone. Millions of people were affected by the cyclone. The neglect of the affected because of the lack of financial and technical resources led to political anger. A million people were killed in the military reprisals as a result and 10 million people fled to India. While the world watched with inaction, India and Pakistan went to war and it was only in the aftermath of this political and military conflict that Bangladesh was born.

Birth of Bangladesh

A quick glance at Bangladesh’s history reveals how unkind nature has been to the tiny country that lies to the east of India. Every year, floods wreck havoc on Bangladesh’s agricultural fields and render thousands homeless. If floods spare the country, cyclones do not. These two phenomenon a have played crucial roles in shaping Bangladesh’s political history.

On November 12, 1970, a severe cyclone, racing at 196 km per hour, hit the southern part of Noakhali, Bhola, Monpura and Patuakhali. It was accompanied by a massive tidal surge 4.5-9 metres high. The cyclone ravaged 800,000 hectares of what was then East Pakistan’s mid-coastal lowlands and low-lying areas in the Bay of Bengal and left as many as 500,000 people dead. The storm razed more than 400,000 houses and 3,500 public buildings. Roads, bridges, and large parts of the Sunderbans mangrove forest were destroyed. The damage was estimated at a staggering US$ 1.2 billion.

Two days after the cyclone hit East Pakistan, Agha Mohammad Yahya Khan, the chief martial law administrator and President of Pakistan, arrived in Dhaka. His indifference to the suffering caused widespread agitation. The unrest was led by Mujibur Rahman, the late Bangladeshi leader who had severely opposed Pakistan’s apathetic stand towards his country. Yahya Khan announced a national election on December 7, 1970. The Rahman-led Awami League won 160 out of the 162 seats allotted to East Pakistan in the National Assembly, largely because of local dissatisfaction with Pakistan’s administration and to management of the after month of the cyclone.

Tension mounted between the two leaders and the number of troops sent into East Pakistan soon reached 60,000. When talks between Rahman and Yahya failed, the latter initiated a military crackdown on March 25, 1971. In a struggle that lasted for nine months, an estimated 3 million lives were lost at the hands of the Pakistan Army.

Soon after the crackdown, approximately eight to ten million refugees streamed into the eastern Indian state of West Bengal. With the leading nations of the world twiddling their thumbs, the Indian Army was deployed in East Pakistan. The war that took place from December 4-16,1971, ended with Pakistan’s defeat and the birth of Bangladesh.

Sources:

1.Bangladesh-Federal Reserve Division of the Library of Congress, edited by James Heitzman and Robert Worden.

2.Fazlul Quader Quaderi 1971, Bangladesh Genocide and the World Press, in TIME, May 24, reprinted and enlarged in 1997.

3.Hossain, Dodge and Abed 1992, From Crisis to Development.

We obviously do not want such things to happen in the future. But they do show that it is the poor countries who should have the maximum interest in addressing the problem of climate change.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has already reported that developing countries will be twice more vulnerable than developed countries, because of their economic conditions, and small island nations will be three times more vulnerable. If carbon dioxide concentration was to double, the economic damages and adaptation costs would amount to 1-2 per cent of GDP for developed countries and 2-9 per cent for developing countries.

III – The Kyoto Protocol

Soon after the Framework Convention on Climate Change (FCCC) was adopted, the countries moved on at the first Conference of Parties (COP-1) held in 1995 to accept the Berlin Mandate which pointed out that as the industrialised countries are the main sources of greenhouse gases, they should take the lead in addressing the climate change problem by setting time-bound targets for emission reductions. The Berlin Mandate finally led to, in 1997, the Kyoto Protocol which provides legally-binding time-bound targets for emissions reductions for the industrialised countries with respect to their 1990 baseline.

The Kyoto Protocol is made up of three key elements:

1. The baseline approach and voluntary but legally-binding emission reductions as a percentage of the baseline emissions. For most countries the baseline is the year 1990 emissions though some countries have been given the option to chose other baseline years.

2. Flexibility mechanisms like Joint Implementation, Clean Development Mechanism and Emissions Trading which allow industrialised countries not to reduce their emissions as required under the commitments in the Kyoto Protocol within their own countries but to obtain emissions reduction credits from other countries in order to meet their own targets.

3. The principle that industrialised countries will take legally binding emissions reductions commitments now but developing countries will take them later.

Let us analyse the implications of each of these elements of the Kyoto Protocol, especially from the perspective of developing countries.

3.1 The baseline approach

The baseline approach has major adverse implications from the standpoint of the ecological effectiveness of the Kyoto Protocol. The more inefficient is the energy-economy of a nation the higher will be its emissions and, therefore, such a nation can take higher emissions reduction commitments because they can be undertaken by that nation at comparatively lower costs. On the other hand, a nation with a more energy-efficient economy can take only lower emissions reductions commitments because it can undertake emissions reductions only at a comparatively higher cost.

This gives developing countries a perverse incentive to increase their emissions as much as possible in the short term and, thus, develop as inefficient energy-economies as possible so that they can undertake higher emissions reductions commitments at a lower cost when their time comes to accept such commitments.

Given the fact that the politics at the third Conference of Parties (COP-3) held in Kyoto mainly revolved around emissions reduction targets of nations who were only prepared to accept low targets even though they were seen as the main countries causing damage to the global atmosphere, it is clear that countries which are able to take greater emission reduction commitments in the future will be seen as the best nations in the world. Especially in a future scenario in which global warming is taking place and is visibly seen to be causing serious damage to the world ecology and economy, all nations, including developing nations, will be under severe pressure to accept as high commitments as possible regardless of their past history of emissions.

3.2 Flexibility Mechanisms

The following comments can be made about flexibility mechanisms (flexmex) :

One, whether they are called Joint Implementation, Clean Development Mechanism or Emissions Trading, they are all essentially the same. All are forms of emissions purchasing and selling. These elements have been given different names because of a ‘diplomacy of terminology’. Joint Implementation has been strongly resisted by developing countries. Therefore, Joint Implementation, as embodied in the Kyoto Protocol, essentially relates to emissions trading at the project level between industrialised countries. Because developing countries have consistently opposed the Joint Implementation concept, North-South collaboration on climate change, as embodied in the Kyoto Protocol, is called the Clean Development Mechanism instead of Joint Implementation. This is again emissions trading at the project level but between industrialised and developing countries. Emissions Trading is yet to be fully defined but essentially means emissions purchasing and selling amongst industrialised countries as embodied in the Kyoto Protocol.

Two, flexmex allow emissions reductions to be exernalised instead of being internalised. In other words, flexmex allow a nation not to take domestic action but to take credit for emissions reductions through projects and through trading with other countries. The US government has the maximum interest in flexmex because it seeks the lowest cost options for emissions reductions which are not available within the energy-efficient economy of the United States. On the other hand, the European Union (EU) with an interest in ecological effectiveness wants more ‘domestic action’ and, therefore, a cap on the use of flexibility mechanisms.

The US argues that flexmex are cost-effective for meeting its emission reductions targets and it does not matter where the emissions reductions take place because ultimately the whole world will benefit from them. On the other hand, the EU says that ‘domestic action’ is necessary to prevent global warming.

It is obvious that the benchmarks of economic effectiveness and ecological effectiveness are at loggerheads here. The EU position is that if industrialised countries do not actually reduce emissions at home, then, given the fact that their emissions are already very high in order to prevent global warming, reducing emissions in other countries do not help very much.

Stuart Eizenstat, who was the main US negotiator at the fourth Conference of Parties (COP-4) held in Buenos Aires in November 1998, had strong disagreements with the EU position.

In a speech delivered on October 28, 1998, a few days before COP-4 entitled ‘Fighting Global Warming: From Kyoto to Buenos Aires and Beyond’, he said:

“In Buenos Aires we will oppose any backsliding on the grand bargain that was struck in Kyoto. At Kyoto, we joined others in taking on a strong emissions reduction target. We did it with the clear understanding that like the European countries have done with their bubble, we would be able to use the flexible, market-based Kyoto mechanisms without arbitrary limits to meet our obligations cost-effectively. That agreement must hold.

“We will adamantly oppose efforts to set arbitrary limits on trading. They threaten to undo the Kyoto agreement, and would impose unsustainable costs on the US economy and actually discourage deeper reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

“We will stress that the Buenos Aires conference should avoid polemics regarding caps on the flexibility mechanisms and concentrate instead on developing a work plan and a working group process, with clear time tables for elaborating the rules for trading and other market mechanisms.”

Why are flexmex so important for the United States? Let us look at a few numbers that have been given out by its policy makers about the costs that the US would have to undertake to reduce emissions. Janet Yellen, Chairperson of the White House Council of Economic Advisers gave these figures to the US Congress.

| Cost of reduction | When emissions reductions are obtained through |

|---|---|

| US $14-20 / ton of carbon equivalent | Flexmex with developing countries |

| US $30-50 / ton of carbon equivalent | Flexmex with Eastern European countries |

| US $125 / ton of carbon equivalent | US domestic action |

Table 2 – Cost of US Emissions Reductions: Domestic action vs Action through Flexmex

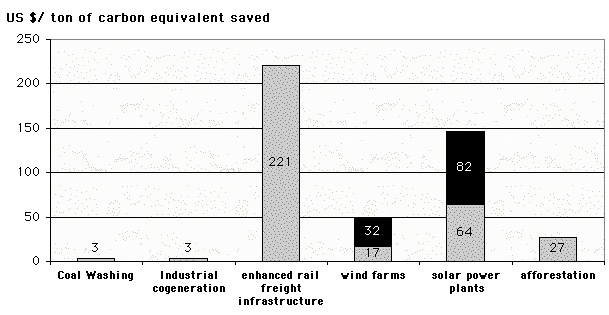

The figures of US $14-20 per tonne of carbon for emissions reductions that Yellen gave in the case of flexmex with developing countries compare well with the calculations that have been made for emissions reduction costs in various studies carried out for the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Bank for various emissions reduction options in India. Studies conducted by these organisations show the costs given in graph below.

Graph 1 – Emission reduction options for India

Rough calculations carried out by Sivan Kartha of the Stockholm Environment Institute in Boston show that the cost of carbon abatement is US $50-110 per tonne of carbon if power were to be generated today from solar power stations instead of coal-based power stations. (See table below)

| Cost Item | Coal-based power station | Solar power station |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon emissions (assuming coal has 29.3 MJ/kg and 75 per cent carbon, coal plant efficiency is 35.1%) | 260C/kwhr | 0 gmC/kwhr |

| Capital cost | $1653/kw | $2185/kw |

| Operating/maintenance costs | $47/kw-yr | $8.8/kw-yr |

| Fuel cost (assuming coal cost is $2/GJ) | $0.02/kwhr | $0.00/kwhr |

| Total electricity cost at 0% cost of capital | $0.034/kwhr | $0.047/kwhr |

| Cost of saved carbon | $48/ton of carbon equivalent | $48/ton of carbon equivalent |

| Total electricity cost, at 10% cost of capital | $0.05/kwhr | $0.118/kwhr |

| Cost of saved carbon | $107/ton of carbon equivalent | $107/ton of carbon equivalent |

Table 3 – Cost of carbon saved when switching from a coal based power station to a solar power station

Note:

1. Assuming 85% capacity factor for coal, 25% capacity factor for solar, and a 30 year lifetime.

2. Cost of saved carbon is defined as net present value of costs (at specified discount rate) divided by total carbon saved.

But to get exact figures for India, specific details of the Indian context will be needed like cost and performance of local coal and solar plants, carbon content of Indian coal, etc. An earlier study done for the World Bank had looked at four alternative electric supply options – wind farms, industrial cogeneration, solar thermal power plant, and demand side efficiency – for a 500 MW addition to the Chandrapur power plant in Maharashtra. (See graph)

The cost of one tonne of carbon reduction ranged from a low of US$ 3 to US$ 64-82. The cheaper options lay in energy efficiency improvements within the carbon energy economy while the more expensive options lay in the non-carbon energy economy.

It is clear that the US is very keen to meet its emissions reduction targets by mopping up as low cost emissions reductions as are possible. Most of these options lie in developing countries. In fact, most companies across the world would also be very interested in doing the same to improve their competitiveness in a global economy. They, too, would look for emissions reduction options which are as cheap as possible.

In order to make sure that the lowest cost options are available to industrialised countries and their firms, the World Bank has come up with a scheme called the Prototype Carbon Fund. Ostensibly the purpose of this scheme is to reduce the transaction costs that would be incurred by companies in sourcing appropriate projects. But this initiative will also mean that developing countries will have to compete with each other through a portfolio of projects that the World Bank will develop, which will drive down emissions reduction costs for firms in industrialised countries as low as possible. Only those projects will get picked up from the project portfolio which offer the lowest emissions reduction costs.

In such a market-based mechanism, it is obvious that poorer countries such as those in Africa will get very few projects because they may not be able to compete with other countries with relatively more advanced economies. For this reason, at COP-4, African countries expressed a keenness for regional quotas under the Clean Development Mechanism so that a certain number of projects would definitely go to African countries.

The Clean Development Mechanism has set a major race within the United Nations and related agencies who all want a share of the pie as brokers in the mechanism. These include the World Bank, UNDP, UNCTAD and UNEP who are all competing with each other to promote the mechanism. Instead of educating developing countries about the best options that are available to them within the negotiating process, including the pros and cons of CDM, they are all pushing for it.

All this is indeed great for countries been on CDM but what does it mean for developing countries?

1. It means selling off cheap options today. But because these options are limited, developing countries will have to undertake more expensive options tomorrow. So for a few dollars today, developing countries will pass on more expensive options to their coming generations.

2. It means getting a rather small amount of money.

Let’s look at three possible scenarios for the US as shown in Table 4.

| Scenario | Emissions credits needed from developing countries (billion tons of carbon equivalent) | Cost over the commitment period (US$ billion) | Average cost/year during the commitment period (US$ billion) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. US stabilises its emissions at 1990 levels by 2008 and purchases its entire emissions reduction target from developing countries | 0.473 | 6.6 - 9.5 | 1.3 - 1.9 |

| 2. US emissions grow unchecked and reach 35 per cent above 1990 levelsnn(a) US purchases all its emissions reductions from developing countries to meet its Kyoto targets | 1.825 | 40 - 57 | 8 - 11.4 |

| (b) US purchases 50% of its emission reductions from developing countries to meet its Kyoto targets | 0.913 | 20 - 28.5 | 4 - 5.7 |

Table 4 – Emissions reduction costs for the US through CDM with developing countries

If the US were to stabilise its 1990 emissions by 2008, it would need to reduce its 1.35 btC emissions of 1990 to 1.26 btC by 2008 to achieve its 7 per cent reduction target. It would have to do so during the entire 5 year commitment period of 2008-2012. US can get all the emissions reductions that it needs – 473 mtc – from developing countries for a mere US$ 7-10 billion spread over the five years of 2008-2012. It is during the commitment period that the industrialised nations are expected to ensure that the commitment target is met as an average over the commitment period. In other words, all that developing countries will get is about US $1.4-1.6 billion a year, which is a tiny fraction of the current Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) and even World Bank spending.

A second scenario would be that the US continues to allow its emissions to grow unchecked. By 2008, some estimates say that the US emissions could be 35 per cent over its 1990 levels, in other words, its annual emissions would reach 1.83 btC by 2008. In that case, the US would need to purchase 2.84 btC emissions over the commitment period. The cost of obtaining these emissions from developing countries would be US$ 40-57 billion over the commitment period or US$ 8-12 bn per year during the commitment period.

Assuming the US obtains only 50 per cent of its emissions reductions from developing countries and the rest through other flexmex and domestic action, developing countries would be able to sell emissions credits worth US$ 20-28 bn over the commitment period or US$ 4-6 bn per year during the commitment period.

3. Once low cost options are exhausted in developing countries and only more expensive options are left, the very future of CDM and its rationale disappears because then Annex 1 countries will have no interest in a flexibility mechanism like the CDM. They will then argue that it is economically better for them to go back to domestic action. But developing countries will then be left with more expensive options. Their stock of cheap options would have been exhausted. As the United States and other Annex 1 countries would have taken little domestic action till then, climate change would still be a serious threat and by then there will be great pressure on developing countries to start reducing their emissions. But they will have to do so at a much higher cost. The pressure will, of course, be the highest on larger developing countries which include India and China, because their total emissions will be quite considerable in the years to come.

3.3 The problem of banking emissions

The flexibility mechanisms offer scope for another unsavoury situation. What if the US and other Annex 1 countries were to mop up a very large amount of emissions reductions at low cost from developing countries and in that process exceed their emissions reduction commitments? The Kyoto Protocol allows such countries to bank these excess emissions reductions to meet future emissions reduction commitments. If that were to happen, Annex 1 countries would have a bank of emissions reductions they have obtained at much lower cost from developing countries while developing countries would be left with no other option but to reduce their own emissions reductions at a much higher cost.

This would indeed be a very interesting scenario in the future. Whether this will actually happen or not is difficult to say but the Kyoto Protocol definitely provides for such a situation.

IV – So what was the politics at Buenos Aires ?

1. Given the fact that the United States has said very clearly that unless there is meaningful participation from key developing countries it will not take the Kyoto Protocol for ratification to the US Congress, it means that the Kyoto Protocol may never become a reality. The Kyoto Protocol is so designed that unless United States and Russia join it, it can never become an operational international law.

The NGOs, therefore, exhibited tremendous keenness, especially led by US NGOs, to oppose any obstacle in the way of the United States. In other words, the NGOs presented a hostage syndrome in Buenos Aires, opposing arguments in favour of domestic action as well as equity and entitlements. It was surprising that even the European NGOs were not very vocal on the issue of domestic action especially within the Climate Action Network, a coalition of NGOs across the world.

2. There were a number of developing countries who saw a great future in the Clean Development Mechanism, and who were egged on by a number of a consultancy type NGOs from the developing world who saw a major brokerage role for themselves. The Tata Energy Research Institute in India, for instance, is one of those NGOs which strongly supports the Clean Development Mechanism. Such countries were essentially working within a salivating syndrome without realising that they were essentially drooling over peanuts.

3. The Group 77 and China, however, stuck together at Buenos Aires, despite several efforts to drive a cleavage amongst them. But their weakness was that they were not proactive enough to propose the kind of international agreement they want. In addition, there was a strong need to build an alliance with the European Union which wants caps on flexibility mechanisms. A EU and G-77 alliance is very important because we must remember that it was such an alliance which got the Berlin Mandate in the first place. The Berlin Mandate became a reality only because of the G-77 and EU alliance even though the mandate was not something that the US was very happy with.

A lot of developments took place in Kyoto because there was no effective G-77 and EU alliance working there.

4. The US politics itself is extremely complicated. There is no real evidence to show that the Clinton-Gore administration really wants to put much pressure on developing countries. Unfortunately, it has wilted under the pressure of the US Congress which in turn has bought the argument of the oil-automobile lobby that global warming is, firstly, not a serious issue and, secondly, any international agreement is meaningless unless there is participation of key developing countries.

| Actors | Behavioural patterns at Buenos Aires |

|---|---|

| USA | The tough guy syndrome |

| NGOs | Hostage syndrome - Do not upset the US |

| Argentina, Kazakhstan | Salivating syndrome - Get what you can |

| UNEP, UNDP, UNCTAD, World Bank, consultancy type Third World NGOs like Tata Energy Research Institute | The commission syndrome - lets play the broker |

| Group of 77 and China | Solidarity syndrome - lets stay together |

| European Union | The Shadow boxers: Wanted to push the bench-mark of ecological effectiveness and domestic action by Annex 1 countries |

Table 5 – Actors at Buenos Aires

The only answer to this entire situation is for G-77 and China to go on a diplomatic offensive, be proactive in providing the framework that is needed, get the civil society to support such a framework, and let Clinton and Gore have a chance to show real leadership in preventing probably the biggest environmental challenge facing all of humanity. It is clear that the US can do it and so can we.

V – So what should be the proactive strategy of the G-77 in Buenos Aires ?

Fortunately, the United States has insisted on ‘meaningful participation’ of key developing countries without which it will not accept the Kyoto Protocol. Therefore, developing countries have been given an opportunity now to define what they mean by ‘meaningful participation’. They should seize this opportunity with full gusto.

We would propose the following proactive strategy for the developing world :

1. The poor nations must insist on the principle of equitable entitlements. They can trade their unused entitlements on an annual basis. This will give poor nations the right to grow economically. The trading mechanisms could still be JI, CDM and Emissions Trading as identified in the Kyoto Protocol but they will then embody not just the principle of economic effectiveness but also the principle of equity and global solidarity. Without this principle, the G-77 should refuse CDM outright. In other words, developing countries should accept the market approach advocated by USA but as long as their rights over the atmosphere are clearly defined.

The Non-Aligned Movement has already endorsed the principle of in South Africa and the EU Parliament has also accepted the principle of equity. (see box Non-Aligned Movement votes for equity and EU: Will it or won’t it?)

2. The poor nations should insist that the principle of convergence should be accepted within the Kyoto Protocol framework.

3. The poor nations should insist that flexmex must be pegged to a non-carbon energy transition. In other words, the selling of least cost options should not be permitted as long as they are within a carbon-based energy economy. This will also build into CDM the third objective of ecological effectiveness.

Non Aligned Movement votes for equity

The heads of State or governments of the Movement of Non-Aligned Countries met in Durban, South Africa in early September 1998, to address crucial global issues affecting their peoples with the view to agreeing to a set of actions in the promotion of peace, security and development, conducive to a new system of international relations based on the principles of justice, equality and democracy.

The final document, under the sub-heading Environment and Development, addresses climate change, as follow :

Paragraph 342

The Heads of State or Government welcomed the Kyoto Protocol on legally binding commitments for the parties to the Framework Convention on Climate Change to reduce their emission of Greenhouse Gases as contained in Annex B of the Kyoto Protocol. They called on the developed countries to undertake urgent and effective steps to implement these commitments through domestic action. Emission trading for implementation of such commitments can only commence after issues relating to the principles, modalities etc. of such trading, including the initial allocations of emission entitlement on an equitable basis to all countries has been agreed upon by the Parties to the Framework Convention on Climate Change. They categorically rejected all attempts by some developed countries to link their ratification of the Kyoto Protocol with the question of participation by developing countries in the reduction of GHG emissions. They also called for immediate measures to provide the developing countries with necessary financial resources and clean technology to enable them to meet their existing commitments under the Framework Convention on Climate Change, including inter alia, inventorisation of national emissions and dissemination of knowledge of climate change.

Paragraph 343

The Heads of State or Government urged developed countries to implement effective measures, to cope with their commitments in terms of the reduction of emissions of greenhouse gases in their own territories and highlighted the need to avoid the so-called ‘flexibility mechanisms’ of the Kyoto Protocol enabling those countries to elude the fulfilment of their commitments. In this connection, the launching of the Clean Development Mechanism, established in terms of the Kyoto Protocol, could bring about risk and opportunities for the sustainable development of developing countries that must be adequately addressed.

Source: NAM 1998, Final Communique adopted at the NAM Heads of State Conference, Durban, September, mimeo.

4. The poor nations should insist that no banking of emissions which are obtained through CDM from developing countries will be allowed.

It is possible for developing countries to get the principle of equitable entitlements included in the principles, rules and modalities of the Emissions Trading system which have not been defined in the Kyoto Protocol. Developing countries must not sit back and allow these rules to be set without their participation because the Kyoto Protocol allows Emissions Trading between Annex 1 countries only. They should make sure that these rules are set in such a way that the system allows their concerns to be built in at this stage itself. Because, later on, when developing countries are asked to accept commitments, they would have to accept the emissions trading systems that has already evolved.

EU: Will it or won’t it?

In climate negotiations, the EU has backtracked more often than it has been on track. The EU strategy seems to be to flex its muscles mainly in response to its domestic environmental constituency. But on each issue it finally, after much fanfare, gives in, using US obdurateness as its favorite excuse. During the run up to the signing of the climate convention at the Rio Summit, it made noises about the need for a carbon tax. But gave in quickly citing US pressure. During the many months leading to the Kyoto Protocol, the EU talked loudly and boldly about the need to cut emissions drastically by 15 per cent of 1990 levels and no loopholes of being able to buy the future. But gave in. Post Kyoto, the EU had taken the high morale ground saying that it was important to curtail emission domestically. In June, presenting its position to the joint meeting of the subsidiary bodies to the convention, EU had strongly argued for the need of a cap on how the amount emissions that could be bought. In September there was a move to go back on this commitment. The draft resolution of the European Parliament in a complete turnaround said that was needed was “maximum degree of flexibility, including joint implementation and trading in emission rights consistent with the proper monitoring, reporting and enforcement of the global cap on emissions.” It then took the might of the articulate environmental community in Europe to reverse this damage. The final resolution of the European Parliament stresses the need for “an agreement to have a quantitative ceiling on the use of flexibility mechanisms that will ensure that the majority of emission reduction to be met domestically.” Ritt Bjerregaard, EU environment commissioner has however said that caps are not needed. And British environment minister Michael Meacher who had made a publicised speech to the GLOBE parliamentarians calling for a ceiling of 50 per cent in the use of flexible emissions seems to be having cold feet. Reportedly only four EU countries are now supporting the 50 per cent target; Denmark, Germany, Luxembourg and Austria. The European environment council has now come up with an “innovative” approach to appease all sides. The draft council conclusions on climate change adopted at the EU ministerial council meeting in early October discuss three “options”. The paper reaffirms the “concrete ceiling on the use of flexible mechanisms has to be defined in order to ensure that those mechanisms do not undermine domestic actions.” But now it gives a menu of options on the ceiling. Option one, define as 50 per cent of the emission targets. Second, to use quantitative or qualitative criteria, involving early domestic actions to demonstrate progress. And, third option is to define the ceiling as a percentage of the emissions in 1990 or 1995.

The chipping away has begun. It now remains to be seen if the EU will remain true to its position or will go back on its principles, once again.

VI – Why is the non-carbon energy transition so important ?

Because it is the only way to prevent global warming. No plan of action can meet the benchmark of ecological effectiveness unless it is built on a clear understanding that the world has to move towards a non-carbon energy transition as fast as possible. No amount of improvements in energy efficiency can bring US emissions from, say, 5 tonnes per capita of carbon down to 1-0.5 tonnes per capita in the foreseeable future. It is only the non-carbon energy transition which can allow such a thing to happen. Annex 1 countries should neither be under any illusion or create any illusion that the Kyoto Protocol strategy will solve anything to prevent global warming without factoring in a rapid transition towards a non-carbon energy transition. Nor is it possible for the Kyoto Protocol strategy to keep developing country emissions to low levels if they remain within the current carbon-based energy economy. India and China, for instance, have enormous amounts of coal and if they were to build a large number of coal-based power stations commensurate with their growing economic needs and a carbon-based energy grid increases to serve everyone’s energy needs in the developing world, there will be no way to prevent global warming.

A carbon-free economy

All these intractable problems can, however, be surmounted if the world makes a serious effort to move towards an energy economy that is built on sources that are carbon-free like solar and biomass energy, wind power or hydroelectricity instead of the existing reliance on fossil fuels like coal, natural gas and petroleum-based fuels. Then the threat of climate change will get arrested and each nation would be free thereafter to use as much energy as it wants.

A recent study points out to the benefits that will accrue to the world in combatting climate change with the rapid phasing in of solar energy technologies. This is the only study I have seen which shows the impact of phasing in of solar energy on future carbonisation of the atmosphere. Instead of global carbon emissions continuing to grow constantly for nearly 180 years and reach a peak of 49 btC (billion tonnes of carbon) in 2175 with average global temperatures rising to a maximum of 6°C (relative to the base year of 1860), emissions will peak in 2035 in just 40 years at about 37 btC and start declining thereafter if research and mass production can keep cutting the cost of solar energy technologies by 50 per cent every decade. By 2065 solar energy would have become competitive with fossil fuels to the extent that it will replace fossil fuels in every economic sector.

Even a relatively pessimistic scenario in which solar energy costs decline by 30 per cent per decade will make a salutary difference. If this latter scenario is accompanied with a carbon tax on fossil fuels of about US $100 per tonne, then the latter scenario will become as effective as the more optimistic scenario in which solar energy prices fall by 50 per cent every decade. (See table 6 and graph 2)

| Scenarios | World GDP loss in first 100 years | Use of oil and coal reserves | Presentation of solar energy in 2100 | Peak emissions | Global temperature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline modelnn(We are currently following the baseline model. The model predicts1995 emissions at 7.2 btC. Actual emissions were about 7 btC.) | 1.3% in first 100 years and up to 5.2% by 2285 | All oil and coal reserves consumed | 370 years to move completely to solar energy | In 2175 at about 49 btC | Rises to a maximum of 6°C relative to the base year of 1860 |

| Decreasing cost of solar energy by about 50 per cent per decade (DCSE 50) nOptimistic Assumption : Electricity conversion cost reaches 4 c/kwhr in about 4 decades | 0.32% in first 100 years | Only 1.5% of world's estimated coal reserves are exhausted | All economic sectors run by solar energy by 2065 | In 2035 at about 13 btC | Rises by 1.5°C and declines after 2055 ; Global mean temperature in 2195 is the same as 1995 |

| Decreasing cost of solar energy by about 30 per cent per decade (DCSE 30) nPessimistic Assumption : Electricity conversion cost nreaches 4 c/kwhr in about n7 decades | 0.74% in first 100 years | Only 8% of world's estimated coal reserves are exhausted | All economic sectors run by solar energy by 2105 | In 2055 at about 18 btC | Peaks in 2095 and takes 320 years to reach 1995 level |

Table 6 – Impact of solar energy on future CO2 emissions

DCSE: Decreasing Cost of Solar Energy

btC: billion tonnes of carbon

Source : Ujjayant Chakravarty, James Roumasset and Kin-Ping Tse, Extraction of Multiple Energy Resources and Global Warming,

University of Hawaii, mimeo.

Thus, the rapid penetration of solar energy technologies in the energy sector has the potential to turn the threat of climate change into a problem that would last only for a few decades in the early part of the 21st century instead of a problem that will continue to threaten human beings for centuries to come (see table below).

| Sector | Dominant energy in Baseline Scenario (business as usual) | Year of shifting to solar: Baseline Scenario | Year of shifting to solar: DCSE 50 Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity production | Coal | 2280 | 2030 |

| Transportation | Oil up to 2079, then coal | 2300 | 2030 |

| Residential | Gas up to 2050, then coal | 2340 | 2040 |

| Industrial | Oil up to 2020, then coal | 2350 | 2060 |

Table 7 – Energy resource use sequence: Baseline Scenario vs Rapid Solar Transition Scenario (adapted)

Source: Ujjayant Chakravarty, James Roumasset and Kin-Ping Tse, Extraction of Multiple Energy Resources and Global Warming, University of Hawaii, mimeo.

The most heartening thing is that despite all the neglect of solar energy by governments and enormous subsidies to fossil fuels, solar energy systems are already making their way into the market. Annual US sales of solar energy technologies are already about US $1 billion. Photovoltaic technology has already seen considerable advances in the last 20 years and though its costs remain high, they are likely to come down to less than 10 cents per kilowatt-hour early in the next century. Enron and Amoco are already building a 100 MW plant in Nevada, USA and have been looking for funds to build a 50 MW photovoltaic power plant in India.

Pre-conditions for the non-carbon transition

In order to promote rapid expansion in the use of solar energy, there are two important actions that need to be undertaken:

1. Increase research investment

A carbon tax of US$ 5 per tonne of carbon will increase the price of oil by just US$ 0.65 per barrel but it will generate US$ 10-15 billion in the US alone which could be used to fund solar energy. According to the Worldwatch Institute in Washington, DC, less than 9 per cent of energy R&D budgets of industrialised countries is spent on solar and other renewable sources of energy.

2. Create conditions for a growing market for solar technologies so that mass production can further bring the cost of solar technologies down.

This is where a system of emissions trading built on entitlements can play an important role. Developing countries like China and India are growing at a rapid rate. Any entitlement they obtain would get used up rapidly. But as it is unlikely that they can use up their entire entitlement in the immediate future, they would have the potential to trade their unused entitlements. This provision would immediately give them the incentive to move towards a low emissions developmental path so that the benefits from trading emissions can stay with them for a long time.

For example, if India were to find the current high cost of a solar power plant set off by the economic advantages obtained by saving emissions and earning money from trading the saved emissions, as a compared to the lower cost of building a coal power plant, then it is quite likely to think in terms of investing in a solar power project and thus help to create a global market for solar energy technologies worldwide by helping to bring the costs of solar energy technologies down. The economic equation would look something like this :

(The high cost of a solar power plant) – (The money earned from trading the saved emissions) = (The low cost of a coal power plant)

This emissions trading system would, thus, also provide sufficient financial resources and an “enabling economic environment for technology transfer” to take place, as indicated in Article 10 of the Kyoto Protocol.

It is equally important to note that such an economic environment would help to create a global market for Western solar energy technologies – first in developing countries and then later in industrialised countries – and help to kick-start the global transition towards zero emission technologies. This makes sense because of two key reasons: (a) developing countries have more solar energy than Western countries; (b) if global warming is to be averted in the long run, the more solar energy is used by them instead of oil and coal, the better; and, (c) Developing countries have millions of settlements even today which do not have grid-supplied electricity. There are more than two billion people today who have no access to electricity. Solar energy systems should serve these people in the future rather than carbon-producing electric grid systems. Solar energy will be cost-effective in the first instance in such scenarios.

Technological advances are also taking place in using hydrogen as a source of energy which will have major impacts on the transport sector. By 2010, vehicles operated on fuel cells and electric batteries are expected to be on the road which will considerably reduce carbon emissions from the transport sector. Automobile companies are putting in considerable R&D efforts into electric cars. According to media reports, Chrysler has estimated that with a production volume of 300,000, it could produce electric vehicles as cheaply as petrol vehicles except for the cost of the batteries.

But many of these technologies will not reach the developing world unless its special needs are taken into account. If India, for example, were to have as many cars on a per capita basis as USA, it would have 500 million cars as compared to about 4 million that exist today. But in the decades to come India will definitely have a 100 million or so scooters. These vehicles are today 70 per cent of the total number of vehicles in India. Like India, other Asian cities like Bangkok and Taipei, too, are chock full of scooters. But hardly any Western company is thinking of working on electric or fuel cell scooters. This situation needs to be rectified.

Emissions trading would, thus help developing countries to enter into the most “meaningful form of participation” – to borrow the phrase that the US government uses so often.

But then one of the rules of emissions trading would have to be that no trade can take place unless it involves a transition to the use of non-carbon or biomass energy sources instead of trading being the cheapest alternative to the cost of reducing greenhouse gas emissions in industrialised countries as is being proposed by the US. In the latter case, the world will definitely get emissions trading and industrialised countries will be able to do ‘creative carbon accounting’ to meet their emissions reduction targets but climate change would not have been averted.

If the non-carbon/biomass energy transition becomes the benchmark for flexmex, then the costs to the US will be 2-4 times more than those indicated in table 5. Is that a very high price to pay to deal with the biggest environmental threat facing humankind?

VII – The Action Plan

In order to meet the benchmark of ecological effectiveness, the action plan for combatting climate change would have to look as follows

| Region | 1st commitment period | Later commitment periods |

|---|---|---|

| Industrialised countries | Energy Efficiency | Energy efficiency + non-carbon projects |

| Developing countries (through flexmex) | Non-carbon projects | Non-carbon projects |

Table 8 – An Effective Action Plan for combatting Climate Change

Therefore, how do we sum up the position that developing countries should take ?

The first position should be that we should listen to industrialised countries like the United States and agree to the principle that, one, we need markets and, two, we need flexibility mechanisms.

But developing countries should also set their conditions for the nature of the international cooperation that needs to be developed.

And these condition should be:

1. The principle of equitable per capita entitlements must be incorporated as a key principle of Emissions Trading in the Kyoto Protocol.

2. The principle of convergence must be accepted.

3. The rules for CDM must restrict emissions credits obtained from (that is, solar and biomass projects) developing countries to non-carbon energy projects.

The emerging plan of action would then be able to meet all the three benchmarks of ecological effectiveness, equity and global solidarity and economic effectiveness.

VIII – How do we define and develop the principle of equitable entitlements ?

There are two basic approaches to define atmospheric entitlements:

a) One approach is to include historical emissions (that is, emissions since the start of the Industrial Revolution or from 1950 when the post-second World War economic boom began).

b) Another approach is to build a system of entitlements that is based on current and future emissions.

We give below different ways in which each of these approaches can be or have been used to define ‘equitable entitlements’:

8.A. Proposals for Emissions Entitlements that include historical emissions

We give below two proposals that have been made for equal entitlements that take into account historical emissions.

1. Proposal made by International Project on Sustainable Energy Paths

A study prepared for the Dutch government by the International Project for Sustainable Energy Paths in 1989 argued that the average rate of global warming should be limited, as closely as possible, to 0.1°C per decade and, as an outer limit, to an increase of 2°C by 2100 over the present. In that case, the Earth’s temperature would remain within the range that human beings have seen in the period since their evolution two million years ago. This would restrict the sea level rise to a level of about 1 metre whereas a rise of 5-7 m would be absolutely disastrous. This means that the maximum allowable concentration of all greenhouse gases (carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, CFCs etc.) should not exceed 430-450 parts per million (ppm) of carbon dioxide equivalent during the next century, provided these levels decline thereafter. In other words, concentration of carbon dioxide itself should not exceed 380 ppm (compared to 338 in 1980 and 349 in 1985) while other greenhouse gases together add up to another 50 ppm of carbon dioxide equivalent. IPSEP’s calculations show that this means that only a total of 300 billion tonnes of carbon (btC) can be released between 1985 and 2100 or roughly 2.6 billion tonnes of carbon (btC) each year.

IPSEP then asked the question: How should this 300 btC global carbon emissions budget (over the period 1986-2100) be shared?

IPSEP pointed out that this budget should be shared on the basis of human population over the period 1986-2100 (that is, in terms of person-years). Its calculations showed that if the existing and projected populations of industrialised and developing countries between 1986 and 2100 were taken into account, then developed countries would exhaust their entire carbon release quota of 48 btC till 2100 by 1999, that is, if they continue to release carbon dioxide at their 1986 levels. Developing countries, on the other hand, will be able to emit carbon dioxide at their 1986 rate until 2169 AD.

| World emissions | Industrial countries emissions | Developing countries emissions | Years left at 1986 release rate for Industrial countries | Years left at 1986 release rate for Industrial countries | Years left at 1986 release rate for Industrial countries | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTUAL EMISSIONS | ||||||

| 1950 | 1.55 | 1.44 | 0.11 | - | - | - |

| Share (%) | 100% | 93% | - | - | - | |

| 1986 | 5.27 | 3.90 | 1.37 | - | - | - |

| Share (%) | 100% | 74% | 26% | - | - | - |

| 1950-1986 | 127.9 | 104.4 | 23.5 | - | - | - |

| Share (%) | 100% | 82% | 18% | - | - | - |

| SHARED BUDGET | ||||||

| 1986-2100 | 300 | 48 | 252 | 12 | 183 | 57 |

| Share (%) | 100% | 16% | - | - | - | |

| 1950-2100 | 428 | 77 | 351 | Nil | 255 | 81 |

| Share (%) | 100% | 18% | 82% | 8- | - | - |

Table 9 – Sharing the carbon dioxide budget including historical emissions for a 400 ppm carbon dioxide atmospheric concentration and 300 billion tonnes of carbon budget between 1986 to 2100

All figures in billion tons of carbon equivalent.

Source: Florentin Krause et al 1989, Energy Policy in the Greenhouse, International Project for Sustainable Energy Paths, Cerrito, p.15.

The IPSEP study further pointed out that developed and developing countries have been emitting carbon dioxide at vastly different rates for a long time. If this historical inequity is taken into account, and the permissible global carbon emissions budget of 428 btC from 1950 till 2000 is distributed between industrialised and developing countries, instead of the 300 btC global carbon emissions budget between 1986 and 2100, then developing countries can continue to emit carbon dioxide at their 1986 rate till 2241 AD. But industrialised countries had already exhausted their entire quota by 1986. In other words, they would have to stop all carbon dioxide emissions right away.

It is obvious that sharing the carbon budget which takes historical emissions into account provides industrialised countries with so little space for change that, in fact, it provides no space for change. Therefore, it is extremely unlikely that industrialised countries will accept any such proposal. But if developing countries do not insist on historical emissions being taken into account in order to calculate equitable entitlements, then industrialised countries must appreciate the fact that this is a gracious gesture on the part of developing countries.

2. Proposal made by Brazil

A few months before the Kyoto Conference of Parties, the Brazilian government tabled a proposal for sharing the emissions reduction burden. The proposal said that by the year 2000, countries are expected to bring their emissions back to the 1990 level. The 1990 level was termed the ‘effective emissions reference’. By 2020, the Annex 1 countries (that is, industrialised countries) should aim to reduce their emissions to 30 per cent lower than the 1990 level as a group. This level was called the ‘effective emissions ceiling’. The proposal further argued that ‘effective emissions reduction targets’ be established for each of the periods 2001-2005, 2006-2010, 2011-2015 and 2016-2020 for the entire Annex 1 countries.

According to the proposal, all these numbers are not calculated in terms of ‘annual emissions’ as all other proposals do, but in terms of the average global surface temperature (in degrees Centigrade) because emissions can be correlated with temperature changes in the atmosphere. And as it is global warming that the world is trying to avoid, it is better that all numbers are presented in terms of temperature differences that actions of individual nations will make.

But once the ‘effective emissions reduction target’ has been fixed for the Annex 1 countries as a group, the Brazilian proposal goes on to argue that the relative responsibilities and targets for different nations be fixed in terms of their relative share of induced temperature increase in 1990 because of greenhouse gas emissions. As a country’s historical emissions are also contributing to the increase in temperature induced by 1990, countries’ with larger emissions in the past will have to accept a larger ‘effective emissions reduction target’ than others. For example, the proposal pointed out that in 1990, whereas Annex 1 countries were responsible for only 75 per cent of the total carbon dioxide emissions in that year, they were responsible for 88 per cent of the induced temperature increase due to carbon dioxide in 1990. In this context, the Brazilian proposal pointed out that though the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has said that annual emissions of developing and developed countries would equal in 2037, the induced changes in temperature by developing and developed countries will equal in 2147.

| Relative Shares | Annex 1 nations (%) | Non-Annex 1 nations (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Relative share of annual carbon dioxide emissions in 1990 | 75 % | 25% |

| Relative share of carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere in 1990 | 79% | 21% |

| Relative share of induced temperature increase due to carbon dioxide emissions in 1990 | 88% | 12% |

| Relative share of induced temperature increase due to carbon dioxide emissions in 2010 | 82% | 18% |

| Relative share of induced temperature increase due to carbon dioxide emissions in 2020 | 79% | 21% |

Table 10 – Differentiated responsibility for climate change attributable to each group

Source: UNFCCC 1997, Implementation of the Berlin Mandate, Additional Proposals from Parties. Addendum. Note by the Secretariat to the Ad Hoc Group on the Berlin Mandate, Seventh Session, Bonn, 31 July-7 August 1997, Item 3 of the Provisional Agenda, FCCC/AGBM/1997/MISC, 1/Add. 3, pp.20-21..

The Brazilian proposal has also argued for a strict compliance regime. It argued that countries which do not meet their commitments would have to provide a contribution to the Clean Development Fund (CDF) calculated at the rate of US$ 3.33 per effective emissions unit that was emitted higher than the ceiling decided. The fund would be used to finance climate change mitigation and adaptation projects in developing countries.

The Bonn meeting of the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice which was requested by the Conference of Parties held in Kyoto in December 1997 to discuss the Brazilian proposal resolved that the proposal has several outstanding issues that need to be addressed. Brazil agreed to convene a workshop to address these issues at the time of the Buenos Aires Conference of Parties. The EU, the US, Switzerland and Australia expressed reservations in Bonn on methodologies for reconstructing historical emissions, especially in the absence of reliable data on emissions in the past.

3. Proposals for Equitable Emissions Entitlements built on Current and Future Emissions

There are three possible ways, among others, in which emissions entitlements can be built on current and future emissions:

1. By sharing the world’s common sinks (that is, processes that absorb the carbon dioxide and other gases that cause global warming) equitably;

2. By defining the world’s future emissions budget and sharing it equitably; and,

3. By establishing an ad hoc per capita emissions entitlement which all countries will agree to converge on.

We describe below each of these ways.

1. Sharing the world’s common sinks equitably

In order to avoid global warming, the world will have to learn not to produce more emissions than the world’s sinks (that is, processes that absorb the carbon dioxide and other gases that cause global warming). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has pointed out that the 1990 emissions must come down by over 60 per cent if atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases are to get stabilised.

The average annual production of carbon dioxide between 1980 and 1989 has been estimated at 7.1 billion tonnes of carbon equivalent. The average annual absorption by all the sinks for these years was 3.8 billion tonnes of carbon. There are mainly two types of sinks for carbon dioxide, namely, sinks that are based in the oceans and sinks that are based on land.

Nations could well argue that terrestrial sinks are their national property and not global property as the world’s lands are all divided up into different national territories. But as oceans belong to all humankind, it can be legitimately argued that oceanic sinks are the common heritage of humankind. The oceanic sinks are of the order of 2 billion tonnes of carbon per year. As the 1990 world population was 5.3 billion, this gives us a per capita sink availability of 0.38 tonnes of carbon (0.38tC) which can be considered each person’s entitlement. India’s carbon dioxide emissions in 1990 from burning of fossil fuels, gas flaring and cement production was only 0.22tC. In other words, India will then be entitled to increase its emissions up to 0.38tC and, in the meantime, trade the emissions that it is entitled to but is not using or even consider ‘banking’ these unused emissions for future use.

| Type of sink | Amount absorbed every year |

|---|---|

| Oceanic Sinks | 2.0 billion tonnes of carbon |

| Sinks provided by Northern Hemisphere forests | 0.5 billion tonnes of carbon |

| Other terrestrial sinks (Carbon dioxide fertilisation, nitrogen fertilisation, climatic effects, etc.) | 1.3 billion tonnes of carbon |

| Total sinks | 3.8 billion tonnes of carbon |

Table 11 – Size of carbon dioxide sinks

Source: IPCC 1996, Climate Change 1995: The Science of Climate, Contribution of Working Group 1 to the Second Assessment Report of the IPCC, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p.79.

However, this entitlement is so low that not only will India reach the limit very fast, but there are many developing countries which are already emitting more carbon dioxide than this limit. While major developing countries which were emitting less than their entitlement in 1990 included all the seven countries of South Asia, namely, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, Pakistan and India, African countries like Tanzania, Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria, Asian countries like the Philippines and Indonesia, and South American countries like Peru and Brazil, there are other major developing countries like Egypt and China which have already crossed this level of per capita emissions.

2. Defining and sharing a world’s emissions budget equitably

A second concept of entitlements emerges out of the concept of ‘contraction and convergence’ promoted by the Global Commons Institute in London and endorsed by Global Legislators Organisation for a Balanced Environment (GLOBE). Under this concept, the world needs to agree on the upper limit of atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide that would be considered acceptable and by which year this concentration can be reached. These decisions would then determine the total amount of carbon dioxide – the global budget – which can be emitted by all nations on Earth.

This entire budget can be distributed equitably to all people on Earth which would then provide each country with its total budget. This national budget can then be distributed over the entire period during which the agreed atmospheric concentration is expected to be reached. If during a particular year, a country does not use its budget, then it would have the right to trade its unused budget.

The IPCC has estimated the total amount of carbon dioxide emissions that can be emitted in a 110 year period from 1991 to 2100 to reach specified atmospheric concentrations.

| Atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide (ppmv) | Emissions Budget over the period 1991-2100 (billion tonnes of carbon) | Average annual budget over the period 1991-2100 |

|---|---|---|

| 350 | 300-430 | 2.73 - 3.91 |

| 450 | 630-650 | 5.73 - 5.91 |

| 550 | 870-890 | 7.91 - 8.09 |

| 650 | 1030-1190 | 10.27 - 10.82 |

| 750 | 1200-1300 | 10.91 - 11.82 |

Table 12 – Carbon dioxide emissions budgets for different atmospheric concentrations

Source: IPCC 1995, Climate Change 1994: Radiative Forcing of Climate Change and an Evaluation of the IPCC IS 92 Emissions Scenario, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p.22.

If we were to aim for a maximum atmospheric concentration of 450 ppm of carbon dioxide, then the world can emit an average of 5.73 to 5.91 billion tonnes of carbon every year which would have provided in 1990 a per capita entitlement of 1.08-1.12 tonnes of carbon.

3. Establishing an ad hoc per capita emissions entitlement which all countries will agree to converge on

A very simple approach would be for nations to agree on an ad hoc per capita entitlement to which all countries will agree to converge. This entitlement could be anything like 0.5tC, 1.0tC or even 1.5tC. The higher the entitlement, the better it would be for both developing countries and for industrialised countries because then developing countries can go up to higher per capita emissions whereas industrialised nations do not have to go down to levels that look impossible to them.

The problem with high entitlements, however, would be that atmospheric concentrations could reach a point that would lead to a serious heating up of the Earth.

Therefore, a provision will have to be made in the rules that the ad hoc entitlement can be changed downwards or upwards depending on the increasing scientific evidence on the climatic effects of the build-up of carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere. In fact, a key principle of the Framework Convention on Climate Change is that it will consistently take into account the latest scientific information in its decisions. In other words, if scientific information is negative, all nations will accept more stringent measures and if the scientific information is positive, they can take a more relaxed attitude.

In any case, the ultimate purpose of entitlements is not to force every nation to come down to the same level of per capita carbon dioxide emissions, which industrialised countries will probably find impossible to reach as long as they remain locked into a fossil fuel energy economy. But the purpose is to create an equitable framework in which all nations can work together with the assurance that each person is entitled to equity in economic activities as long as they remain without Carbon energy economy and there is sufficient scope for cooperation between the rich and poor countries so that both can move towards a carbon-free energy economy. Because once nations have made the transition from a carbon-based energy economy to one that is carbon-free (based on solar energy biomass and hydroelectricity, for instance), then they will have no constraints on their energy consumption. And the very need for a per capita entitlement to carbon emissions would disappear.

Therefore, the two key purposes of the ‘entitlements’ concept is not merely to ensure equity but also to create a frame-work that helps all countries move towards a carbon-free energy economy as fast as possible. In order to meet this objective, any trade in emissions that is built on this entitlement should be pegged not to least cost options but to those options that promote the use of non-carbon energy sources.

IX – Questions

But one can ask: Isn’t this an adhoc approach? Why promote adhocism?

It is important to remember that there is already a lot of ‘pragmatic adhocism’ in the climate change negotiations. For instance, the amounts that industrialised countries are going to emit by 2008-2010, as specified in the Kyoto Protocol are all pegged to their emissions in the year 1990. The choice of the year 1990 is as ad hoc as anything can be.

But it has been accepted as the baseline year because industrialised countries had to show that they were reducing their emissions relative to some year and as long as they started moving ahead, it did not matter which year was chosen. In fact, countries in economic transition have been given the option to choose their own baseline year. And the amount by which each industrialised country is going to reduce its emissions relative to 1990 emissions has also been ad hoc. Again, all this was done in the interest of simply moving ahead. Similarly, an ad hoc entitlement amount can be chosen in order to get the principle of equity and convergence enshrined in the Framework Convention on Climate Change and get North-South cooperation moving through emissions trading.

How will we deal with ‘hot air’ if we allow trade in the entire entitled amount?

Hot air is another issue of concern because if high entitlements are fixed for all people and if countries, especially those countries, which are unlikely to use up their emissions entitlements in the early years, are allowed to trade their entire unused amounts, this would be equivalent to trading ‘hot air’, in other words, trading emissions that a country was not going to produce in a particular year. Therefore, whereas all people would have the right to increase their emissions to their entitled amounts, there would have to be restrictions on their right to trade those emissions. They could be allowed to trade only those emissions that they would have produced had they not undertaken measures to improve their energy efficiency use non-carbon energy sources.

How will we deal with the problem posed by population growth?

Any system of per capita entitlement can be argued to be unjust to those nations that have stable populations as compared to those which have rapidly growing populations.

With increasing population, nations will be entitled to emit more and more over the years under a per capita entitlements scheme. This could theoretically provide a perverse incentive to them to increase their population. But it looks far fetched to argue that anyone would like to have more babies simply to increase their emissions. This problem can, however, be dealt with by freezing the global distribution of population with reference to an agreed year, which would ideally be the year of the agreement. In this way, no nation can increase its total emissions entitlement. If its population grows, then its per capita emissions will steadily go down.

How will we resolve the contradiction that has been created by the Kyoto Protocol by defining emissions reduction targets for industrialised countries on the basis of their current emissions (that is, 1990 emissions) whereas developing countries may like their emissions management to be based on equitable entitlements?

This contradiction can be easily resolved by accepting both the principles at the same time as no nation would like to unravel the Kyoto Protocol at this stage as long as all nations agree that they will ultimately reach a convergence point. Industrialised countries can start reducing on the basis of reductions on their 1990 baseline of current emissions whereas developing countries agree not to go beyond their ’emissions entitlements’ and undertake measures to change their current and future emissions growth path with the help of resources obtained through emissions trading.

These are all relevant issues for negotiations in order to ensure that the framework for international cooperation is not only ecologically effective (that is, it actually leads to global action that averts serious climate change) but it is also socially and economically just.