Among the facts that sometimes seem to come in handy to explain that the climate change we have set in motion remains hypothetical are weather events that do not seem to fit to the general trend we should expect :

- very low temperatures in winter in the Northern Hemisphere,

- a “rotten summer” in the southern coast of France (but the reader might replace “in the southern coast of France” by any other region in the world crowded with people coming there to enjoy high temperatures),

- lots of snow in the Alps in January….

By reasoning so, and considering that it is not possible that we experience a global warming with such events, we make a very frequent mistake : that of thinking that weather and climate are exactely the same thing, when we are facing two very different ways to consider “what weather there is” .

- Weather designates the atmospheric conditions that prevail “now”, or in the very near future, and “in front of my door”, or not very far. Weather is thus defined by instant and local values of temperature, rainfall, atmospheric pressure, cloud cover, sea surface temperature, etc. To make weather forecasts, it is basically enough to “look upwards”, that is examine what is going on in the atmosphere. To do so, weather organizations use ground stations (measuring temperature, rainfall, ground pressure), sounding balloons or satellites (measuring temperature and pressure above ground, rainfall over large zones, especially the ocean, etc). Once there is a good description of what is going on “above our heads”, over a short time interval (several days), it is possible to simulate what wheather will happen in a given place in the coming days, by “prolongating” over a couple days the observed weather. Models that are used for wheather predictions are therefore purely atmospheric, but it is sufficient to make efficient forecasts : in spite of all we can say, the trend given is generally the good one !

- What confuses us is that when we are discussing climate, we are also considering ground temperature, rainfall, pressure, could cover, sea surface temperature, etc. There is a major difference, though : instead of considering instant and local values, we will consider values averaged over much longuer periods of time, and over large areas : continents or large sub-continental portions. We do not say that we have a temperate climate in Western Europe because the observed temperature in London on the 3rd of January is of 5 °C, but because temperatures are “on average” like this in the winter, and “like that” in the summer, and because there is so much rainfall over the year “on average”, etc. And this “on average” refers to values that have been measured over decades, not only one year, and averages over large zones, not a couple square kilometres.

It is of course possible to go from weather data to climate data : with all the instand values observed throughout the world, it is possible to get average values over several decades and large zones. But the reader will easily understand that the opposite is not true : when we have a given trend on the average values (wich is what we get with climate models), it is not easy – let alone possible, sometimes – to reconstitute the local and instant values of temperature or rainfall. A little exemple derived from everyday life will help us to understand easily that point : suppose that the average mark of a high school class has risen by 2 points over a semester. Are we allowed to deduct, from this single fact, that the result of the little Jones, for a given test, has also risen by 2 points compared to the result of the previous test ? Of course not : it is obviously possible to have the average level of the class rising while while the mark for a given pupil goes the other way round.

For weather and climate, it is exactely the same : it is perfectly possible to have the average value going one way while a givent event goes the opposite direction. If one reminds that any European country covers at most 0,1% of the surface of the planet (and the US 2%), it is then easy to understand that the general warming trend (that is deducted from measurements made over the whole planet and over several decades at least) is not contradicted by a cold winter or a cool summer in France or in Italy or in Florida or in Mogolia.

This is also why, when the question is asked to know whether some unusual event that happened over a restricted zone (restricted compared to the whole planet, of course !) and which is, by definition, a meteorological event, is also the sign of the ongoing climate change, science is not able, for the time being, to give a definite answer : we must wait to see if, “on average”, this kind of event will happen more frequently in the future. In other words, we will get the answer when it is too late to anticipate.

Of course, just as daily weather does, the Earth’s climate also changes, but not at the same rate !

- The largest regional climate change, on short time scales, is of course the seasonal cycle : going from winter to summer (or the opposite) changes the average temperature by several tens degrees at mid-latitudes. But the planetary average doesn’t change by that much : when it is the summer in the Northern hemisphere, it is the winter in the Southern, so that the planetary average temperature changes by only a fraction of degree over the year.

- then, if we stick to annual temperature or precipitation means, we will find large regional oscillations such as those generated by El Nino, that may induce a significant climate change on the regional scale for several years,

- some massive regional climate change might result from a modification of the ocean currents (a good example is given by the “halts” of the Gulf Stream in the past),

- a global climate change that takes a couple thousand years to happen is the begining of an ice age : minus 5 °C in several thousand years for the planetary average,

- and at last the planetary climate can be modified over millions of years, which has been the case, for example, for the slow cooling that our planet has experienced since the middle of the tertiary age. This time, it is the continental drift that is to blame ! (see below)

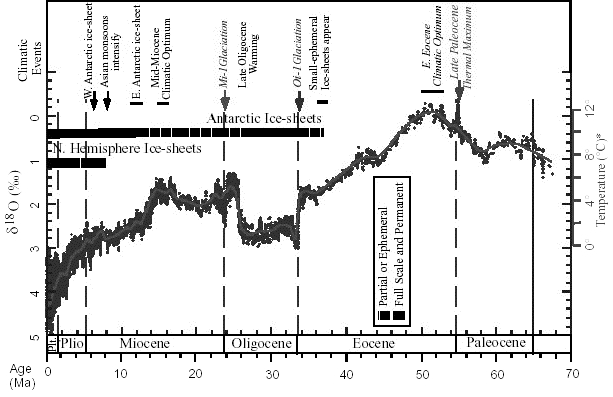

Estimation of the average temperature of the planet (compared to today, the 0 on the right axis being the present temperature) during the last 70 million years.

The horizontal axis gives the time before present, in million years. Be careful ! A graduation represents 2 millions years, and the more one goes right, the more we get back in time.

Let’s recall that the planetary average is today 15 °C, but if we calculate the average over the last million years, we will get something closer to 11 or 12 °C, because Earth has mainly been in ice ages over that time.

Source : Zachos et al., Science, 2001

Of course, any change that is slow “on average” might include oscillations that happen on a fastest pace, but one should avoid to mix up the long term trend with the short term oscillations. A climate change is not a sure thing as soon as the temperature of a given day – or of a given week ! – in a given place has been far from the mean (sometimes named the “usual value”).

Is it enough to “look up” to understand the climate system ?

Another major difference between “weather” and “climate” is that the climate system is not driven only by what is happening in the atmosphere : in order to understand the behaviour of the climate system, it is not enough to “look up”. A lot of other components of our planet – or outside our planet – drive the climate system, and here is a non limitative list :

- the sun, and the varying amount of energy that it radiates, because this conditions the amount of energy that is eventually “poured” in the climate system,

- the astronomical parameters of the Earth’s orbit, that also condition the amount of energy coming from the sun that reaches the Earth, and the way it is dispatched over the hemispheres,

- the composition of the atmosphere, that drives the intensity of the greenhouse effect, and thus the “additionnal heating” of the ground coming from the atmosphere,

- volcanoes, that pour aerosols into the atmosphere, and therefore “cool” the climate,

- oceans, that limitate temperature variations between day and night, or winter and summer, even for someone in the centre of Siberia,

- polar ice caps, on the first hand because their extension drives the global reflection of the Earth’s surface (but it is a secondary cause compared to clouds), and on the second hand because their volume drives the ocean height (during ice ages, polar ice caps are much larger, and as a result the ocean level is much below),

- vegetation, which plays a major role in the local water cycle (trees are good evaporation machines, and on average rainfalls are more important over forested surfaces than over cultivated surfaces), and which also conditions the “reflecting potential” of a given surface : a forest and a field do not reflect the same amount of sunlight they receive, which is of course of some importance for the climate,

- continental drift, that changes the amount of sunlight reflected in a given region. Indeed, oceanic water reflects less sunlight than emerged land : if the continental drift puts some emerged land where there was water, this changes the proportion of reflected sunlight at this precise place, and it influences the global amount of sun radiation kept by the climate system. This continental drift also allows, if emerged land replaces water near one of the poles, the seting up of a permanent ice cap (over the ocean it is only possible to have sea ice, much less voluminous, and not permanent everywhere), that in return will change the ocean level and the global temperature…

- etc.

And at last, if man has without any doubt become one of the forces driving the climate, through an increase of the greenhouse effect, it has not become yet a force able to change the daily weather according to his will !