Lecture given at the “Palais de la Découverte” – may 2001

Published as an article in the november 2001 issue of the “revue du Palais de la Découverte“

Coincidence or wise calculation, I have the honor of closing the week of lectures that the Palais de la Découverte proposed to you on energy by exposing a couple of thoughts on the links that might tie together our energy consumption and the “choices of life” that we make.

The question here will not be to wonder whether we prefer a liberal or a regulated world. This refers to ways of organizing the world that are not final objectives in themselves. The best equivalent for “choice of life” for what follows will be “choice of everyday life”. We will have to know whether we prefer to move fast or slowly, if we prefer to live in cities or “in the countryside”, si we intend to eat a lot of meat (or strawberries in february) or not, well of everything within our existence that goes beyond our basic needs.

Carefully screening these elementary desires – elementary in the sense of unitarian, not in the sense of obvious or legitimate, for we won’t discuss morale here – indeed allows to set a frame for any prospective reflexion on energy.

It is besides quite funny to note that the first question that a normally constituted individual asks himself when dealing with a new problem is, paradoxally, often eluded when our future energy supplies are discussed or that, more exactely, the answer is considered as obvious. Provocation ? Not that much !

What are the questions that are repeated everywhere ? Do we need nuclear energy ? Is wind power a solution ? Should we manufacture efficient cars ? All these questions, that are certainly very interesting, however only discuss the tools, without a preceding debate on what they should be designed for. The central question, though seldom formulated this way, is still very simple : how much energy do we wish ? Must every inhabitant in the world have 1 toe (1) ? 3 toe ? 10 toe ?

This energy, what do we want to get out of it ? And, at last, what are the non-negociaable constraints that we must take into account when we reason ? What are the risks, in other words, that we are ready to run to get our supply, and those that we are not ready to run ? Discussing the means before having answered this question in three parts seems to me as taking the problem by the wrong end.

For the time being, the answer to the question on amounts, never explicitely asked, is at least available in the figures. How much energy do we want ? Always more !

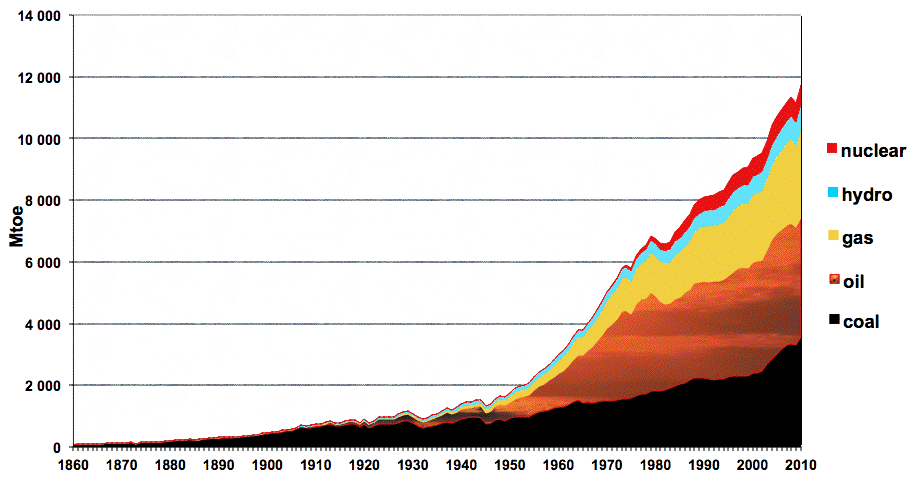

Evolution of the world energy consumption (excluding biomass) since 1860.

Sources : Schilling & Al. (1977), IEA (1997), Observatoire de l’Energie (1997).

The acceleration over the second half of the 20th century is striking, and neither the 1929 crisis, nor the second world war, have significantly influenced the long term trend. One will also note that each form of energy has its own growth : the rise of oil, then gas, did not prevent coal to pursue its own exponential.

It is normal that consumption rises, one will think, since we are more and more numerous on the planet. I won’t teach you anything by saying that it is the case !

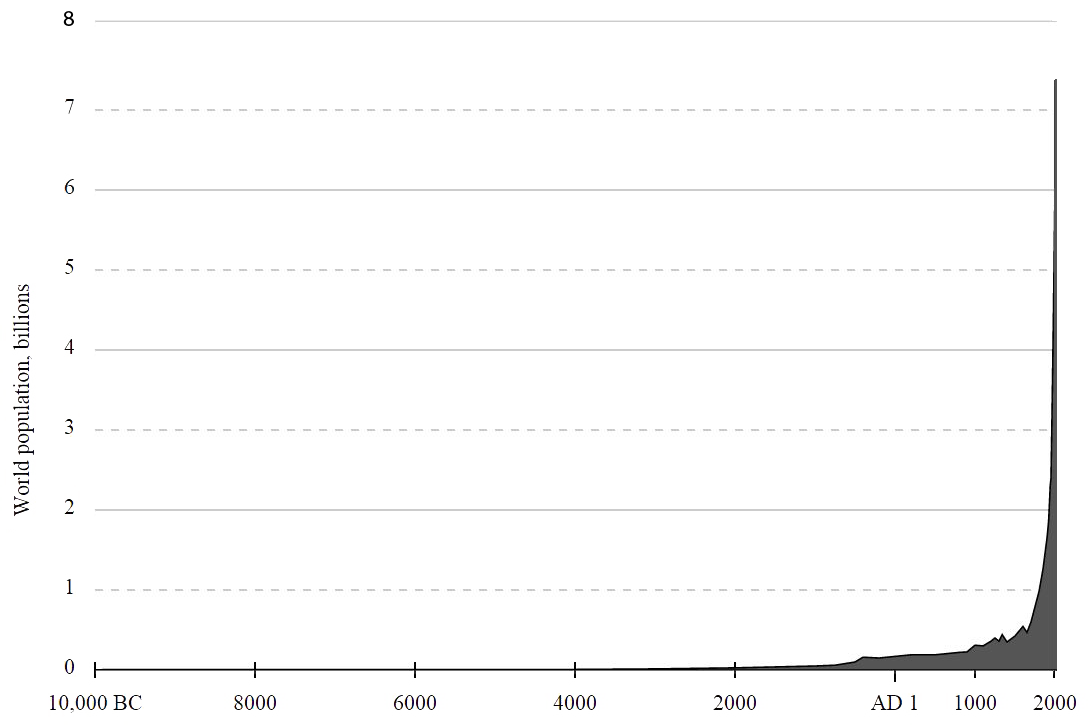

Demographic evolution since the neolithic times.

But it is interesting to note that, if we look at it over a long period, the demographic growth went through an evolution much faster than an exponential one precisely when humankind started to use intensively fossil fuels, that is concentrated energy.

What does this mean ?That many people may mean a lot of energy consumed, but also the opposite : that a lot of available energy allows to sustain a lot of people. The abundance of our species at the surface of the planet would then last no more than the civilization of abundant energy. That’s food for thought !

But we would be wrong to think that demography is the only factor responsible of the “recent” growth : the consumption per inhabitant has also much increased over this period, being multiplied by 7 in a century.

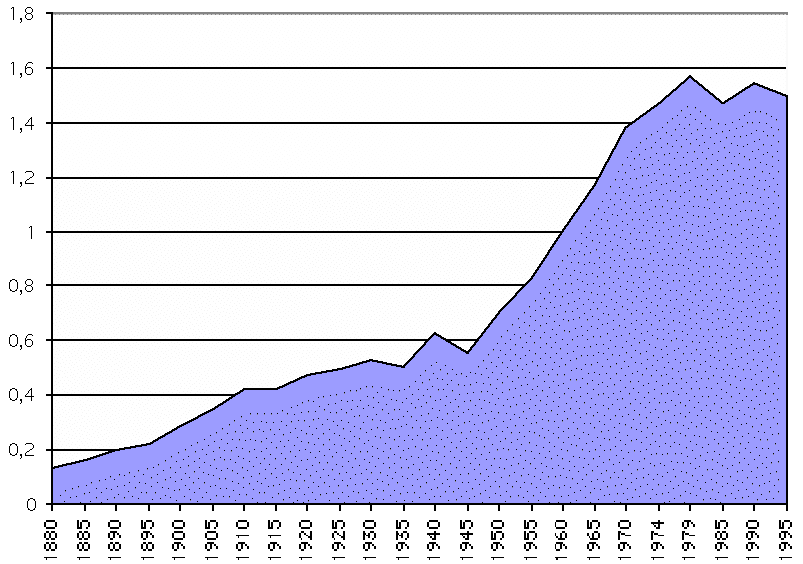

Commercial energy consumption per inhabitant (world average) from 1860 to 1995.

“Commercial” energy excludes wood.

Source : Schilling & Al. (1977), IEA (1997), Observatoire de l’Energie (1997), Musée de l’Homme

1,5 toe (world average today), what does it represent ? Knowing that 1 toe is worth 11.600 kWh, a simple calculation takes us to the conclusion that 1,5 toe per year is equivalent to 2.000 W all the time. A man consuming roughly 100 watts, it means that a inhabitant of the planet has, in rough figures, the equivalent of 20 slaves at his permanent service (120 per American, but still 6 for an inhabitant of Bengladesh).

The world average seems to stabilize since 1980, but it remains far below what an American consumes (7 tonnes oil equivalent per year) or even a European (3 to 4 toe).

Hence this first question, that clearly refers to the choice of life : should we aim that every inhabitant on the planet has the way of life of an American, what is the implicit guideline of the present evolution of the world ? Must each Chinese, Indian, Congolese and Moldavian have a large car for each adult old enough to drive, a house in the suburbs heated during the winter and air conditionned during the summer, more than 100 kg of meat per person and per year, and a supermarket caddie filled up a little more after every shopping session ?

If yes, then, as we will see later, we have answered the largest part of the question about the quantities for the century to come and the risks that we are ready to run to get there, and we can start the discussion on the production means.

One can also consider that following this path generates excessive risks, that I will discuss in a moment. It is then necessary to set a limit, which means that we accept the principle of a restriction in the goods and services that we consume : this is certainly a choice of life. Let’s note that any restriction is not necessarily bad news : my heroin consumption is pretty restricted, and I don’t suffer much from it.

Even if we must restrict our consumption, we can still consider that “poor” countries are entitled to a certain level of material comfort. I will then allow myself to ask this very impertinent question : when is it that one stops to be poor ? When one has enough to eat ? When one owns a TV ? When one owns a TV and a telephone ? When one owns also a car ? When one can put his(her) kids to college ? When one’s life expectancy goes beyond 70 years ? Or, more simply, when one is happy with his(her) living conditions ?

If the last answer is the good one, it seems more urgent to me to suppress ads, that don’t have any other function than to create a permanent frustration, than to put 3 billion people into cars !

One coult argue that “poor” countries are not that poor, but it is we occidentals that are excessively rich ! The least occidental worker today lives in material conditions that are far superior to those of a Middle Ages noble. Fancy a symphonic orchestra for breakfast ? A switch on his radio brings it into his kitchen. Fancy being served for a meal ? A restaurant is here for that. Need to travel 30 km ? His horse drawn cab of modern times will take him there i a glimpse. Fancy a troubadour in his home ? Tv offers some 24 hours a day. Abundant food, physicians and hospitals at disposal, and much more characterize the living conditions of our worker friend, that many people will still consider as “modest”.

Modest compared to what ? And our “inhabitant of poor countries”, even from the “least advanced countries”, has strictly nothing to envy from the 10th century enropean, that lived a 2 to 3 times shorter life, that was often hungry, that was often cold, that was very often ill ; former europeans died from all this in proportions that have nothing to compare with present death rates. Today, no country in the world has a life expectancy lower than 40 years, that is twice as much as what it was in France during the Middle Ages, and it is even exceptional that this life expectancy be below 50 years, which means that every inhabitant of the planet has today a life expectancy at least equal to that of a Frenchman of the beginning of the 20 th century. An Indian living in the year 2000, with his lean $ 300 or $ 400 of GNP per inhabitant and per year, has a life expectancy of over 60 years and acess to many more services than a Frenchman of1900.

But an inhabitant of a “poor” country today is probably much more frustrated than a Frenchman of 1900, that was not permanently fed with images coming from outside and describing living conditions supposedly more favourable than his (it is difficult to envy something one can’t imagine). The genralized access to image and the feeling or emergency that derives from it is certainly a determinant of the first order on our energy demand.

After this little departure from the subject, let’s get bacck to poverty, and this question : what is being poor ? Where and when does poverty stop ? This question is not at all a student’s joke : poverty being a relative notion, defined only on the basis of material criteria, not setting any limits to poverty is not setting any limit to our own material consumption. It is certainly a choice of life, and certainly has an influence on the quantity of energy that we wish to have.

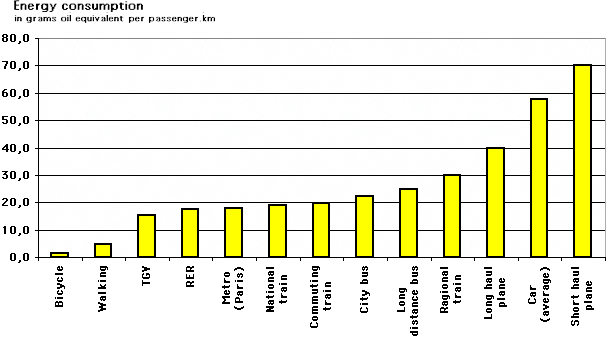

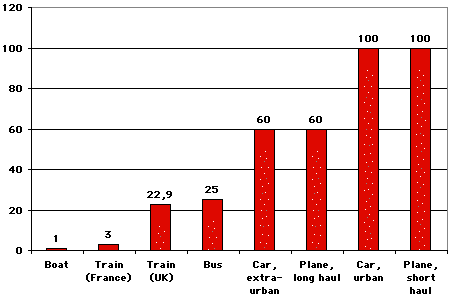

Let’s take the example of moving. Do we want to cycle or to drive ? It is a choice of lifge the way I mean it. The amount of energy used to move will proceed from this choice. Do we want that any individual can take a plane ? The amount of energy used to move will also proceed from the answer. In rough figures, 40 times more energy is required to move on a bike and in a european car (take 80 for an American one), and 50 times more energy is reqquired to move in a plane compared to cycling (graph below).

Energy consumption to move a person over a km, in grams oil equivalent

(1 gram oil equivalent = 11,6 Wh).

From INRETS, ADEME, INFRAS, personnal calculations

A quick glance at the way we use our energy in France will allow to broaden the purpose.

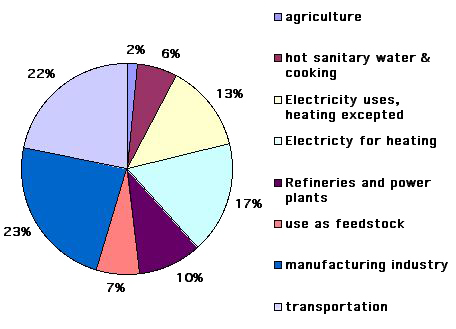

Breakdown of the final energy demand in France for 1999.

Source : Observatoire de l’énergie

Do we wish to enjoy a warm place in the winter ? Then we must use a certain amount of energy to satisfy this desire. Do we want abundant manufactured products ? Then we must also use a certain amount of energy to satisfy this desire. Do we want to eat a lot of meat ? Then we must also use some energy to satisfy this desire : in a kg of beef, there is more than a kg of hydrocarbons !

All these quantities are not that easily manageable “everything equal otherwise”. In other words, the “technique” will not allow us to decrease the amount of energy required to satisfy these desires until it becomes negligible. It is most certainly possible to make progresses on energy efficiency, but the choice of a large car rather than a bicycle, or even of a large car rather than a small one, has a much higher impact than the choice of a recent car rather than an old one (not to mention that the average weight of new cars had a tendancy to increase during the last 15 years).

Just the same, choosing to have 10 or 30 m² of housing space per person is preponderant over the insulation of the building. All this is not very surprising, in the end : a choice of life is characterized by physical values (housing space, speed when moving, etc) and these values are ruled by laws that do not change depending on our will.

Some of you might remember that E = 1/2 * mv² : whatever way we choose to propel it, the tonne that we must set in motion (for our fellow americans : the 2 or 3 tonnes that you must set in motion….) when we drive requires a non reducible amount of energy. Just the same, heating a house in the winter is just maintaining a flow of calorific loss. This flow can be more or less intense, but it cannot disappear.

So far, I did not mention the greenhouse gases emissions, that are also part of the question : how much greenhouse gases do we accept to emit ? Indeed, the amount of fossil fuels that we allow ourselves to consume inexorably proceed from this upper limit. It complexifies a little the question, that then becomes “energy, greenhouse gases emissions and choice of life”.

Presently, the answer to this question on the amount of greenhouse gases that we consider acceptable to emit is also : always more !

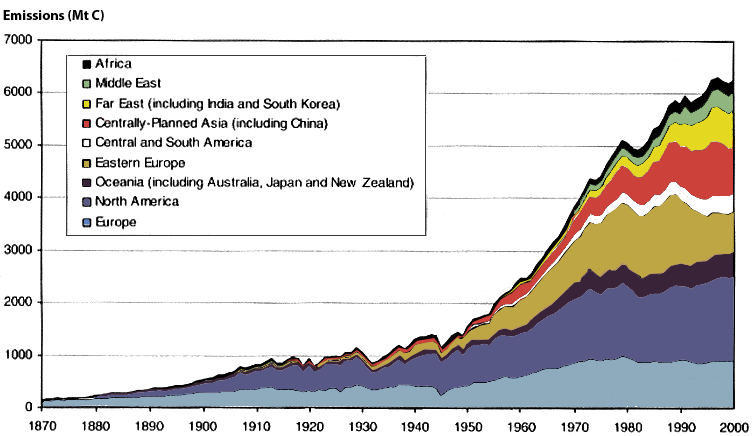

Evolution of the world CO2 emissions coming from fossil fuel use, in gigatonnes carbon equivalent.

(1 Gt = 1.000.000.000 tonnes).

Source : IPCC

Question : Do we know what is an acceptable amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere ? Alas, no. Knowing that the temperatures over the last 400.000 years have never been higher to present ones by more than 1 to 2 °C, and most of all that the conjunction of a high initial temperature and an extremely important rising pace is unpreceeded over this period, no climate specialist can say that it is reasonnable to limit ourselves to an increase of 1,53 °C over 107,5 years ; that below this threshold we are guaranteed against any problem, and that just passing it will lead to a situation in comparison of which the Apolcalypse is a joke.

The only thing that we know is that, in order to stabilize the atmospheric CO2 (that is stabilize the disruption brought to the climate system by the CO2 of human origin, but not to end it), we need to divide the world emissions of this gas by 2 to 3.

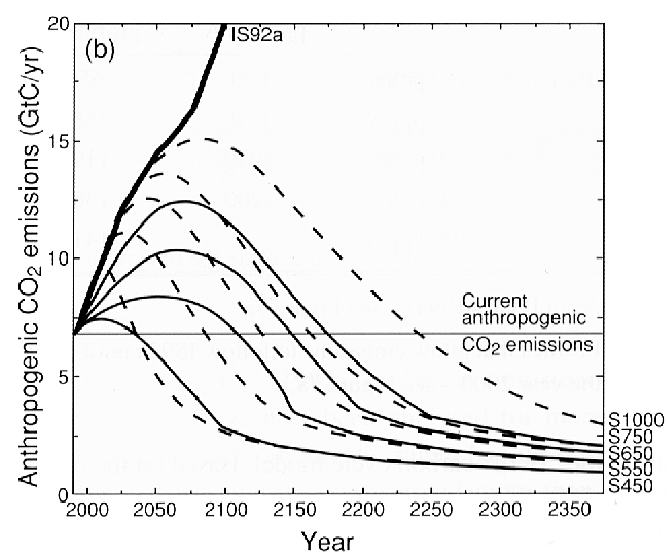

Various emission scenarios.

We see that to stabilize the atmospheric CO2 at a given concentration (curves on the opposite box, that “stop to rise”), whatever value we stabilize at, we need to bend the emissions to 2 to 3 Gt of carbon per year (today they amount to 7 Gt per year).

Source : IPCC, 1995.

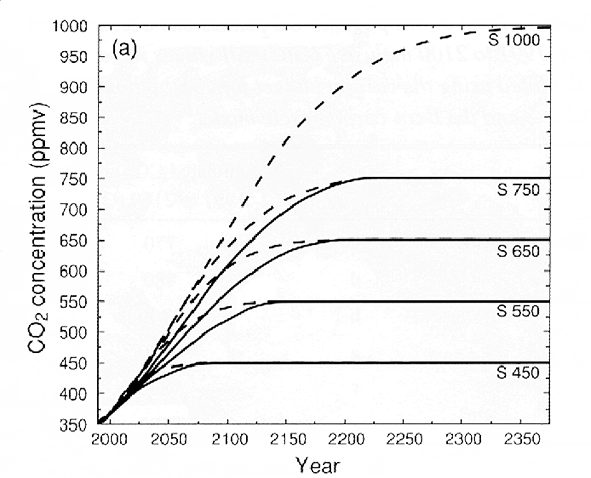

Various possible evolutions of the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere, in ppmv

(1 ppmv = 1 part per million, that is 0,0001%)

Source : IPCC, 1995.

In concrete terms, what does this mean ? That to stabilize the atmospheric concentration of CO2 we need, at a moment or another, that the world CO2 emissions get below 3 Gt carbon equivalent per year, that is 50% at most of the 1990 emissions. The more we delay the moment we get below that value, and the higher the final concentration will be, with the risk that above a certain threshold (around 700 to 800 ppmv of CO2 according to the first simulations coupling the climate system and the carbon cycle) the system gets carried away by the feedbacks of the carbon cycle and that, whatever we do then, the CO2 concentration keeps rising to a level that nobody is able to guess.

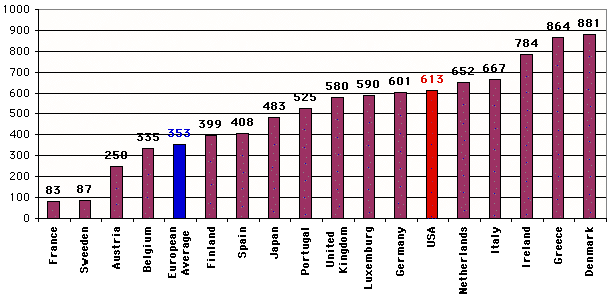

On the grounds of an equitable repartition of these 3 Gt for 6 billion inhabitants, each earth citizen would be entitled to 500 kg carbon equivalent per year at most. This représents :

- 8% of his present emissions if he is American, each inhabitant of this country should therefore divide his fossil fuel consumption by 10,

- 15% of his present emissions if he is German or Dane,

- 20% of his present emissions if he is English,

- 22% of his present emissions if he is French (in spite of the nuclear energy, that we should keep given the context, we must divide our fossil fuel consumption by 4),

- 28% of his present emissions if he is Portuguese,

- 50% of his present emissions if he is Mexican,

- but 120% of his present emissions if he lives in India.

With the current technologies, to emit 500 kg carbon equivalent of CO2 we need to do just one of the following things :

consume 2.500 kWh of electricity in Great Britain, but 22.000 kWh in France,

- or buy 50 to 500 kg of manufactured products (depends notably on the content of electronics or rare metals),

- or use 2 tonnes of cement (building a modern house of 100 m2 requires 10 tonnes),

- or drive 5.000 km in urban zone in a small car (sub-sub compact), that is a couple months’ driving only (the average distance travelled yearly by a car in France was 14.000 km in 2001), or drive only 1 to 2 months in a SUV or a large Mercedes.

- or use 1.000 m³ of natural gaz (that is a couple months of heating a house).

Should we take this “greenhouse gases” criteria into account to determine how much fossil fuels we wish to consume ? If no, we make the choice of a society of material abundance for the short term, but engage in a dead end for the future. If we privilege the long term, as we ask so often to our kids that we oblige to finish their homework before going to play, we must draw the conclusions accordingly for the short term : we must adapt our energy consumption to this constraint, and therefore take a second look at the pie above to decide what we accept to let go, and how we organize ourselves to do so.

Knowing who, between our kids and ourselves, should come first, isn’t it, clearly, a crucial question, even if we come here to morale that I promised not to talk of ? Is it meaningful to discuss to the infinite of the means we are going to use before we have answered this fundamental question : is it necessary to set a limit ?

Incidentally, if we take all the greenhouse gases into account, we just have, to emit 500 kg carbon equivalent, to eat 150 kg of beef. If we take energy and climate change as a whole, we also have to worry about what we eat !

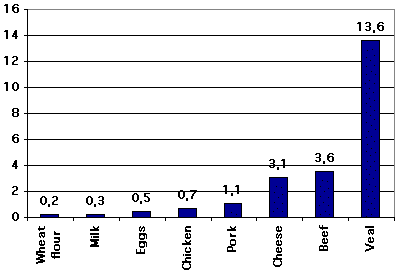

Greenhouse gas emissions linked to the production of a couple foods, in kg carbon equivalent per kg of food.

Source : Jancovici/Demichelis, 2003

As a consequence of the fact that 80% of the CO2 emissions come from fossil fuels, we will find here a couple of questions that are common with the ones evoked previously : do we want to travel from Paris to Marseille by plane, or by train, knowing that one of these possibilities means 30 times more greenhouse gases than the other ?

Greenhouse gases emissions associated with the travel of one person over one km, depending on the mode.

(in grammes carbon equivalent per passenger.km)

And at last taking climate change into account also influences the way to produce electricity (40% of our primary energy consumption in France), obviously.

Grammes of CO2 (caution ! not carbon equivalent, that would be 3.67 times lower) associated with the production of a kWh depending on the country.

Source : IEA.

Doing without nuclear energy suppresses the possibility, for a given amount of greenhouse gases emission, of an extra 1,5 toe per individual. With nuclear energy, dividing our greenhouse gases emissions by 4 in France roughly means to divide the energy consumption by 2, which puts us back to 1970. The same objective regarding greenhouse gases obtained while abandoning nuclear means a division by 8 of our energy consumption, which rathers brings us back to 1900.

The renewable energies having a quite limited potential – I won’t have the time to expose in detail the couple of calculations on the magnitude of the potentials that I have done – and being absolutely unable to replace fossil fuels for a couple toe per person, knowing whether we accept nucleaar energy or not is also an important part of this debate.

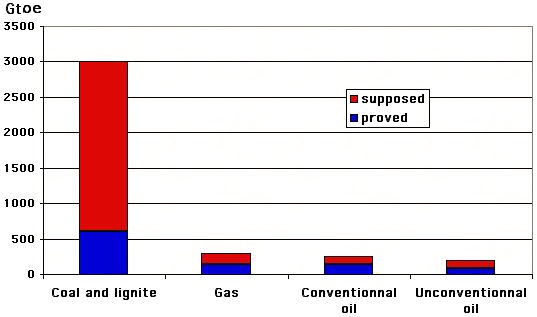

Monsieur de la Palisse wouln’t have said things better : refering to choices of consumption implies that we can choose. For how long still can we “choose” to consume fossil fuels ? The overall reserves amount to 4000 Gtoe (that is 4000 billion toe), of which 3000 are hypothetical.

Breakdown of fossil fuel reserves by nature.

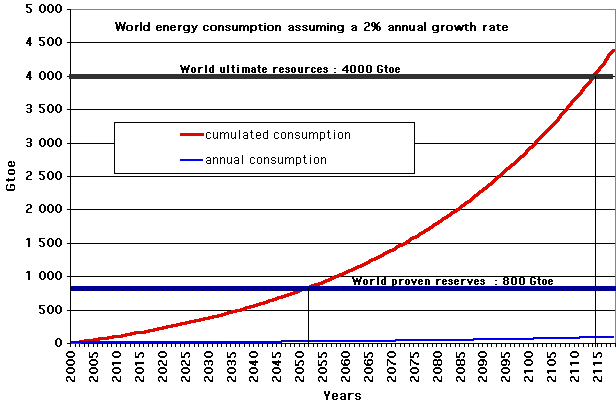

For a world consumption of 8 Gtoe per year, we have more than 4 centuries, are we used to thinking (or saying). Let’s present the things another way : if we integrate a tendencial growth – coherent with the fact that, for the time being, we consider more to put Chinese in cars or planes than to convert ourselves to bicycles – we have consumed all the proven reserves in 50 years and the ultimate reserves in a century.

Consommation annuelle et consommation cumulée depuis 2000 dans l’hypothèse d’une croissance de 2% par an de la consommation, en milliards de tonnes équivalent pétrole.

Is such an evolution impossible ? Not only is it possible, but it is coherent with the implicite objective : get 10 billion people (prolongating the present trends) to the present 7 toe per year of an American (who besides consumes more and more), this leads to a world consumption of 70 Gtoe per year, that would be reached in 2016.

This evolution means among other things that “somewhere” between 2050 and 2100 there wont be abundant fossil fuels any more, when all our daily life – and even daily survival : with no oil and coal starting from tomorrow morning, Parisians would starve – is based on their abundance. One day, by prolongating the trends, there won’t be enough fuels for the Chinese AND the Americans. What will happen then ?

Knowing that, since the Neolithic, a member of our species accpets to kill his neighbour to take from him something he wishes to posess, one might be doubtful about the compatibility of such an evolution with a lasting peace in the world. The fact that occidental countries did not experience war on their own soil and avoided to fight one another for the last 55 years is not, of course, an all-risk insurance for the future.

Such an evolution would also result in the emission of 4000 Gt of carbon in the atmosphere in a century (present figures are 6 Gt per year) If sinks keep abssorbing half of the emissions, we will nevertheless have quadrupled the atmospheric CO2 concentration in 2100 compared to what it is now (1.200 ppmv instead of 360).

Assuming that sinks will never absorb more than 5 Gt per year (today sinks absorb 3 Gt per year, but recent simulations suggest that over 700 to 800 ppmv of CO2 it’s nature that will take after us, and continental sinks will turn into sources, hence 5 Gt per year might still be very optimistic) we get an atmospheric concentration over 2000 ppmv in 2100, that is almost 8 times the preindustrial one.

Once again, the choice of life that consists in keeping the activities and ways of life that we know today, and the postulate that the growth of the consumption of manufactured products by the households is always excellent news, goes with an asociated risk that, if it cannot be precisely quantified, is nevertheless certainly considerable.

Knowing whether we should consume always more, and arouse the desire to do so for those that do not access our conditions today, is much more determining for the future than choosing who we must elect at the next elections.

What does it mean to do the reverse choice ?

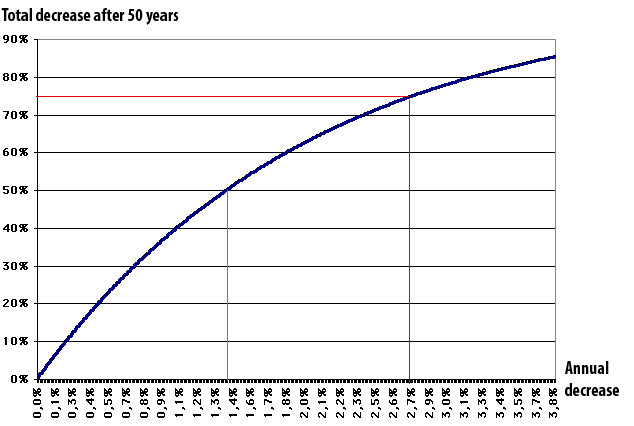

The vertical axis gives the total reduction corresponding to an annual reduction rate (on the horizontal axis) cumulated for 50 years.

For example, a 1,37% annual reduction rate yields a 50% reduction after 50 years.

To cut the energy consumption by 50% in 20 years, we should diminish it of 3,5% per year. This remains within our reach if we make another choice of life, that of restriction, with known advantages and inconvenients : it consists in privileging duration over intensity. This choice is not, clearly; compatible with the “right to everything without limitation for everyone”.

The first determining factor of our energetic future is therefore not technical, but cultural, and knowing that we have long gone over the threshold of the indispensable to survival, what will happen beyond 10 or 20 years isn’t governed by any fatality, any morale, but just the consequences of our choices of way of life, or our “choice of life”.

Notes

(1) toe means tonne oil equivalent, a conventional energy unit equal to 42 billion joules, or 42 million btu, or 11.600 kWh. 1 toe corresponds to the total energy freed as heat by the combustion of one tonne of “standard” oil.