Power of the media

It is quite frequent that, at the end of a conference, somebody asks me how come “nobody seems to be aware of” what I am talking about, because it seems so huge. Abundant and cheap fossil fuels, that are the base of our whole modern world, could end in a couple of decades, and climate change could severely impede – or even make impossible – the life of our grandchildren, and it would not be in the paper: how can it be possible ? Of course, a fraction of the audience then starts to look for possible explanations – or possible culprits ! – and several hypothesis then come very often to the mind:

- scientists do not “do what they should” so that the information is vulgarized enough,

- politicians are afraid to “say the truth”, and “they know” but don’t dare to talk about it.

What amazes me the most is not that these two assumptions are largely unjustified. Climate change offers a rare example of knowledge transfer organized on a very wide scale, through the IPCC, between the scientists and the policymakers (it is thus not possible to accuse the scientists of wrongdoing or just sitting there doing nothing), and – in spite of that, should we say – the vast majority of politicians that I met, or for whom I have first hand information, know almost nothing – which is not much, indeed – of the “energy and climate” file (this is true regardless of the political side).

No, what amazes me the most is that the media are most often forgotten when one wonders about the transmission of information, though it is precisely their part ! Indeed, what other body has the assignment to spread the information from a population of scientists and experts, that represents several hundred people for France, and several ten thousand for the planet, to the general population, that amounts to 100.000 times more ?

A little anecdote will illustrate, better than a long development, this frequent omission of the media in the way we get informed. I remeber reading, a couple of years ago (alas I forgot where exactely) the result of a french poll where the question was: who do you trust for your information ? NGOs scored an impressive 80% of favourable opinions, when the press (or the media, I don’t remember) did no better than 30%. But, I wondered, who gives us the information issued by the NGOs, if not…..the media ?!?! Good logics would then have required that “NGOs in the paper” were not trusted more than the paper as a whole…..

Is it possible to do without journalists to inform on climate change ?

It is of course possible to spread information on this topic without being in the paper, and some willingly use the various possibilities:

- It is possible to make conferences (good for me, because I do !). Suppose I make one conference per week (less 6 weeks of vacation per year, still, we French are a lazy bunch…), for an average audience of 100 people. When I die, let’s say in 40 years maximum, I will have directly talked to 40 (years)*46 (weeks per year)*100 (people per conference) = 180.000 people (roughly), that is less than the fith of the average audience of a national daily newspaper. I should do more than 2.000 years of lectures to reach 10 million people, that the 8 o’clock TV news of the first french channel reaches – on average – every day of the week !If every expert of climate change in France (let’s admit that I self-confer that qualification to me, since everybody seems to consider me as such) does the same, we will get, over la lifetime, to a population that will represent at best the cumulated audience of a couple newspapers on a week day.

- It is possible to write a book. I did it too, I even wrote one and a half (L’Effet de Serre, that I co-wrote with Hervé Le Treut, accounts for 0,5, then there is L’Avenir Climatique), what theoretically increases a little the direct spreading of information. However the cumulated sales of these books is about 10,000 copies as of today (in French only !), what still does not represent a significant fraction of the French-speaking population (because my (co-)books get also sold outside of France, believe it or not). Furthermore some readers are the same for the two books, and readers also overlap with people that I face during my conferences.Here again, if every expert writes a book (but it is not the case), we will totall (in France) 100.000 to 200.000 readers at best (because there are overlaps again), that is less than 1% of the people who vote: as far as “large spreading” is concerned, it is certainly possible to do much better.

- It is possible to edit a website, and that also I have tried : it works ! It brings a number of “readers” more important that the two other ways mentionned above. My modest website went just over 1,000 daily visitors for the first time in march of the holy year 2004, but the average for the 12 last months is rather around 15,000 monthly visits, because the audience is increasing a lot in spring (because of scholars I suspect).

As every visitor reads 4 pages on average, I can “spread” about 60.000 pages per month on average, or 2.500 “equivalent books” per month (knowing a book has 250 pages on average), which is 5 times more than the “paper” version of the book. This being said, contrary to book sales that seldom include people that bough it twice, there are visitors that come several times during the month, and even come back from one month to another: the population that I really reach does surely not amount to 15.000 french readers by month, and even by year it is not certain.

Of course I am not the only one to edit a website, but here again only the riches get richer : there most certainly is a significant overlap of “my” audience with the audience of the other websites that offer vulgarization on climate change.

In comparaison, about 50% of French aged 15 and more read regularly a daily newspaper, national or regional (IPSOS, 2001). 4 titles have more than 2 million daily readers, and the 8 o’clock news of TF1 smashes everyone, with 10 million people watching it (15% of the population), ranking before the news of France 2 (about 6 million people).

It is therefore obvious that the vast majority of my fellow citizens, once they leave school, will only get information on this subject, all their life long, through reading the paper, listening to the radio, or watching TV. In other terms, the bulk of French voters (and this conclusion can probably apply to any other democracy) will never have any other information, as far as climate change and energy are concerned, than what the journalists in charge of these subjects in the various media will have wished to – or been able to – tell them.

Whoever is interested in the widest spreading of information must therefore ask oneself, first of all, if the journalists correctely synthetize the available elements. Did they take the time (or did they have the time) to understand thoroughly what was explained to them ? Do they present facts, or their personal conclusion based on what they understood ? If it is a conclusion that they give (which is most often the case), is it been based on a sufficiently deep investigation, or is it derived from a cursory glance, or even a couple slogans ? How is it possible to know, from the outside, in what conditions has the information been elaborated ? And, at last, when the subject discussed is highly technical (which, regarding energy and climate change, is definitely the case !), is the initial training – or the culture – of our friends from the media well suited to enable them to be at ease with the information they have to manipulate ?

Of course, I do not pretend to bring a definite answer to all these questions, and here as always one must be careful not to draw a general conclusion from his sole experience. Furthermore the problem is happening worldwide, and it would be logical for me to try to obtain answers to these questions (on the quality of the work of journalists) for the whole planet, which is not possible. The elements below, obtained from my little experience, are worth what they are worth to try to explain the multiple limits met when it comes to vulgarizing the climate change file.

A couple elements on the way a media operates

The first thing that one should know is that a media – this is valid either for a paper or for a TV – is, before anything else, a huge sorting center. Any editorial staff receives daily much more information than it can handle (hence synthetize), without even mentionning what it can spread, or what it “should know” without having the time – or the motivation – to learn it (this is particularly true for technical subjects). Each day, it receives hundreds – if not thousands – wires from news agencies, press releases, calls from people “that have something to say”, letters or messages from readers, articles from fellow journalists, etc.

From this neverending flow, the editorial staff much choose what subjects will be included in the daily (or weekly, or monthly) edition, and what subjects will not be (but is it appropriate to suggest it is censorship when the main reason is a number of lacks: of space, of time, of skills ?), the space granted to each information, the people that will be interviewed, what will be kept of their words, the images that will be showed if we’re on TV, the people that will be authorized to publish a tribune or a letter in the reader’s section (for tribunes, a paper receives 5 to 20 times more offers than what it can publish, and for readers letters the ratio is probably 1 to 50 or higher), and, if it is an interview, it is still the editorial staff that chooses the title and the sentences highlighted.

One should know, in particular, that an interview is unfortunately not the warranty of an information delivered directely “from the producer to the consumer”. Indeed, during an interview the journalist generally collects much more information than what it will be possible to print or broadcast. It is then the journalist that did the interview that will decide – in a sovereign way – of the final version of an interview, even though the person interviewed has reviewed his “declarations”. There are of course journalists (I know some) that always ask for a thourough checking of what they wrote, and make a point of not changing a single comma after they get the text edited by the author of the answers, but the opposite situation (a text never submitted for checking, or revised at the last minute without asking to the person interviewed whether (s)he agrees) does frequently happen, and, “seen from the outside”, the reader has no way to know whether the declarations printed are exactely what the the interviewed person said, or if more or less significant changes happened during the transcription.

And when the interview is for a radio or TV, there is no possibility of “correction” whatsoever by the person interviewed, and it is the journalist that will decide alone of what will be broadcasted (and hence what will not). The audience has no way to know whether the portion of the interview that will be on the air represents 2% or 80% of what the interviewed person said in front of the microphone or the camera, and the audience doesn’t know any better how the selection was made when the interview lasts 30 minutes for 30 seconds that will go on the air.

Before we even take a closer look at the particular case of climate change, a first conclusion should be drawn: the mere existence of a massive – but unavoidable – selection done by the media in the available information bears perverse effects, as massive, and as unavoidable. The elements put forward in the paper may well be non-significant compared to the rest of the known facts, they might include mistakes, included because of a lack of time to check, or just because the person that affirms them “looks good”, they might be have a totally different meaning because the context is not recalled, etc.

Is the “climate change” file a simple one ?

Let’s be serious: of course not. If we try to give a first description of what there is in this “climate change file”, here’s what we will find:

- information on the physical processes governing the climate, and on the additionnel effects resulting from human activities,

- information on the risks associated with the future climate change (not to be mistaken with the consequences already visible),

- information on the activities that cause greenhouse gases emissions, and therefore on the use of energy and the agricultural practices,

- multiple points of views on the possible “technical” solutions that we might call on to solve part of the problem : energy savings, “dematerialization”, material decrease, nuclear energy, renewables, etc,

- reflexions on the “good way” to organize ourselves in order to voluntarily curb emissions: international treaties, information of the consumer, possible adaptation of the taxes, of the transportation system, of our agriculture, more or less constraining regulations for the industry or the consumers, etc

This is quite a lot for starters ! And our friends of the media will have a couple of additionnal difficulties to overcome:

- for the scientific basis, a majority of the information is published in English, and I don’t know the fluency of the “average” French journalist in this tongue…. (because I’m French, you see, but this thought can probably apply to all countries where English is not an official language, which is still quite a lot),

- there is a large amount of “scientific truth” in the definition of the problem (there are not two truths regarding the heat capacity of water, the wavelength of the infrared absorbed by carbon dioxide, or the laws of the fluid mechanics), but on the opposite there is no “scientific truth” regarding solutions, as they mix physical possibilities, technical feasibility, and most of all social acceptance or desires (and regarding this last item there is hardly any “scientific truth”, for sure !),

- there is almost no scientist that has a transversal view of the problem, because a researcher is generally highly specialized in a restricted field. So, if a journalist asks to a physicist working on climate models elements on the physical processes that design the climate machine, or how accurately these processes are represented in the models, (s)he will get an answer. But if the said journalist asks to the said physicist what could be the consequences of a 3°C average temperature increase on agriculture, if nuclear energy is a good idea, or whether we should raise taxes on fossil fuels, the physicist will become much less talkative, because these items will not fit into his(her) direct field of interest, or even will be part of a “social issue” on which (s)he will not feel like expressing a public opinion.On the other hand, the agronomist that knows how plants might react to such or such agression will not be the greatest specialist of the evolution of the future climate, and will not necessarily have information on the future availability of energy, that conditions the possibility to use machines or chemical fertilizers, etc. Getting a global view hence requires to pick some knowledge in tens of different specialities, what a scientist of a given field does not necessarily have the time to do (but far from me the idea of reproaching it to them: they are paid for the exact opposite, that is thourough investigation in a restricted discipline). So a journalist will have to identify clearly what kind of questions correspond to what kind of researcher, and it is not that easy.

All these difficulties are finally quite well represented if we take a close look at the IPCC production (see what the IPCC is on this other page). Every 5 years, more or less, the IPCC publishes an assesment report in 3 volumes, that presents the knowledge reagrding the influence of men on climate (volume 1), the possible impacts of climate change (volume 2), and the mitigation possibilities regarding human induced climate change (volume 3).

This report just synthetizes what has been published in the scientific litterature during the recent years, to draw a general picture of the situation (see the description of the “making of” of this assesment report on another page). More precisely, volume 1 (the science of climate change), 650 pages thick for 12 chapters, summarizes about 70.000 pages of various scientific publications (personnal estimate on the basis of 15 pages par reference quoted in the report), which means that to go from what is published in the scientific reviews to what is written in this report, it has been necessary to compress the information by 100 !

Volume 2, that discusses impacts of climate change and adaptation possibilities, follows the same rule: it summarizes, in a little more than 700 pages, about 100.000 pages of publications in scientific reviews. Volume 3 at last, that discusses the mitigation possibilities of climate change, is a little less thick, but we will meet the same ratio between “initial information” and “summarized information”.

| Volume | Number of pages | Number of pages of the references quoted (personal estimation) | "Compression ratio" |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume 1 of the 2001 IPCC assesment report: the science of climate change | 645 | 71 150 | 1 over 110 |

| Volume 2 of the 2001 IPCC assesment report: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability | 724 | 102 100 | 1 over 140 |

| Volume 3 of the 2001 IPCC assesment report: Mitigation | 563 | 42 300 | 1 over 75 |

| All volumes | 1932 | 216 000 | 1 over 112 |

Before we even discuss in detail international negociations, the multiple ways of decreasing individual emissions, the “carbon content” of this or that, the opportunity to call on nuclear energy, and more, here we are with 2000 pages (in English for the French journalist) of information, summarizing more than 200.000 pages of specialized litterature, where it is basically all physics, chemistry, biology, and, in the last volume, economics.

Of course, not a single journalist of the general press has read this assesment report in full (and not a high ranking politician in France, and probably not one in any other occidental countries), and not even a significant fraction of it. It has to be acknowledged, of course, that such a reading – very technical – would anyway be very arduous for the vast majority of French journalists, that followed arts studies (see below).

In order to try to cure that problem, the IPCC publishes with each report a “summary for policymakers”, that is available in many other languages than English, and that has been read by a number of journalists above zero (but I would not swear that it exceeds a couple of handfuls in France !). As these “summaries for policymakers” (one per volume) are only 15 to 20 pages thick (depending on the volume), and therefore represent only 1 / 4.000 of the information enclosed in the scientific or technical articles that feed the assesment reports, these “summaries for policymakers” have been criticized in the past, because they do not allow to expose all the nuances of the full reports. Given the “compression ratio”, it is hard not to do so ! The other solution would be that every “policymaker” (and in particular every journalist) takes the time to read the full reports….

Eventually, the last difficulty to overcome is that it is not easy for a journalist to understand the very different nature – and thus the implications – of each volume:

- the two first volumes deal with “hard” science (first volume), or “semi-soft” (second volume, that deals with biology, medical matters, ecology – with the meaning of “ecosystems study”, etc), and globally stick to the description of the problem,

- the last volume (“mitigation”) is of a very different nature: discussing the possible evolutions and solutions, it does not always clearly distinguishes between projections and forecasts, or technical feasibility from social or economic acceptance (knowing that social acceptance and economic acceptance are sometimes two different names for the same thing). One feels that it has been partially written by economists that do not have a high technical expertise on the subjects discussed (at least it’s the impression that I got from the lecture of the chapters devoted to energies “without carbon”).

Before concluding how much all these journalists are an incompetent lot and endless liars, one must remember that the exercise they have to deal with is not really an easy one. Let’s end this little “difficulty tour” with the fact that the job is very often to be done from one day to the next, when it is not for the same day: the majority of journalists that contact me and work in a daily media need the information “on the spot”, and sometimes the information that the audience will find in the paper or on TV is not the best available, but just the one that the journalist could get that day….

Where do the journalists that cover climate change come from ? (in France)

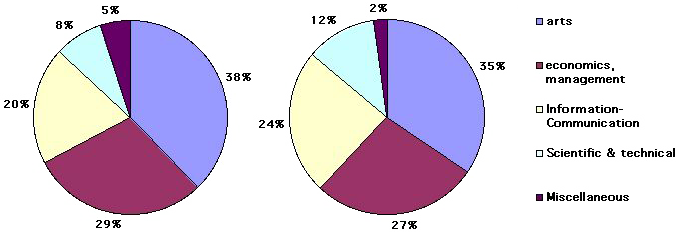

In 2003, France had about 35.000 journalists owning a press card. I do not have data on the initial training of all active journalists, but a research institute (part of the French CNRS) performed a specific investigation in 2000 on a large sample of “newcommers” of the years 1990 and 1998, that is the journalists that got their press card those years.

Breakdown by initial training of samples of the new owners of the pres card in 1990 (430 people) and in 1998 (380 people).

“‘Arts” designate Languages studies (such as English or German), Litterature, Philosophy, History, Geography, and Arts in the “artistic” sense,

“Economics and Management” designate Marketing, Law, Economics, Political Science and Social Sciences.

Source: Devenir journalistes, Denis Ruellan & al., La Documentation Française, 2001 (publication following a job done by UMR 6051 du CNRS).

In addition to this first information, which is that french journalists overwhelmingly have an non scientific training, one should know that the vast majority of those that do have a scientific or technical training get employed in specialized media: medical magazines, computer/software magazines, etc.

In short, the “major” national media giving general information (in France, but I suspect other countries are not radically different), be they written or audiovisual, rely almost totally on journalists having a non-scientific training to inform on climate change, where scientific and technical data is everywhere. Let’s be clear: recalling that most journalists do not have a scientific training does not reflect a will to run them down (I would not feel comfortable at all if I had to run tomorrow a chronicle offering analysis of some decisions of the higher jurisdiction, or on medieval China !), but the reader “has the right to know” that (s)he who is in charge of transmitting information on climate change must often deal with notions that (s)he seldom saw during his(her) studies, and that this objective fact, combined with delays that are frequently very short, is definitely a major handicap to offer a synthetic view of the problem.

What journalists offer information on climate change ?

Most of the time, a media is organized just like a government (this is true worldwide): a given topic is assigned to a given section, just like a given problem is assigned to a given ministry in a government, and other journalists do not deal much with the same information. The media thus experience the same partitioning of information than in a government, with a sectoral approach that hinders, just as in a government, a transversal presentation of the problem, though the latter is often necessary to understand correctly the ins and outs of the subject.

Indeed, to get to a good overview of the climate change problem – and energy use – one has to understand a large number of interactions (between eating and greenhouse gases emissions, between transportation and greenhouse gases emissions, between economic growth and climate change, and even between a possible drying of the southern bank of the Mediterranean Sea and future immigration !). Practically speaking, it will be very difficult to present these interactions, because they do not easily fit into the three sections that will – most of the time – inherit of the task of providing information on climate change:

- the “environment” section,

- the “science” section,

- the “international” section (for the negociations).

The other sections are generally not concerned. For example, everybody (well almost everybody !) now knows that transportation is a major cause of greenhouse gases emissions.

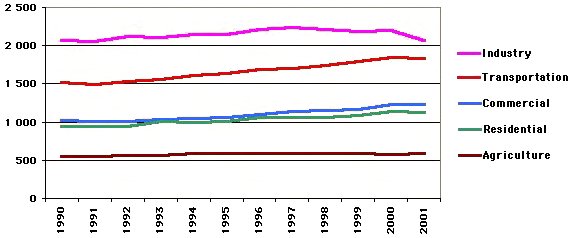

Breakdown of the US emissions by end-use from 1990 to 2001, in million tonnes CO2 equivalent.

Source : EPA

In spite of this, articles that we will read, reporting the building of a new highway, a new airport, a new parking lot, the disclosure of the operating profit of car manufacturers, the launching of a new plane, etc, that are written by journalists in charge of transportation, or industry, or regional news, are generally totally mute on the consequences of the main information on greenhouse gases emissions, hence on the climate change problem.

It is also exceptional to see climate “popping up” in the “economy” section (though there is an obvious link !), and when it is the case most of the time it is to assert nonsense (like: acting against climate change is “bad for the economy”), or in the various sections that deal with “everyday life” (who will be bold enough to recommend not to buy beef because it has one of the highest “greenhouse gas contents” of all foods, or what TV journalist will always recall the emissions “embodied” in a plane travel when reporting on the Olympic Games ?), or even in the “politics” section (what journalist wonders on the consequences on greenhouse gases emissions of any promise made when runing for a mandate ?),

This partitioning easily leads to an incoherent treatment of information, as the journalist in charge of section A might very well assert the total opposite of what the journalist in charge of sector B will say, the reader being in charge of sticking the pieces together the best (s)he can (when reading conclusions that say everything and the exact opposite, should one consider that it is information, or disinformation ?). Rather than engaging into a long discussion, I reproduce below a message that I sent to the director of the french paper Le Monde on january 25, 2004, and will perfectly illustrate my deepest thoughts (I never got any answer, but it is not the reason why I reproduce it !).

Dear Director of Le Monde,

Periodically, your paper (…) regrets our lack of will to act with determination against an announced climate change that could bring our planet to experience the equivalent of a change of climatic era in one or two centuries, then leading to a modification of our environment that would happen at an unprecedented pace since our species appeared on Earth.

As often if not more, your paper exposes how cars over 200 HP are desirable (a full page in today’s edition ; the praise of whatever Porsche model I don’t remember a couple of weeks ago, etc), the same attitude applying to plane travel to the Tropics (a 8 or 9 page supplement, that I did not keep, 1 or 2 (?) months ago), all things that are perfectly incompatible with the necessary division of the greenhouse gas emissions by 4 in France if we want to get to a start regarding the solution to this problem. No morals here, just physics. (…)

Most certainly, the pages that regret the consequences while we praise the causes are written by different journalists, but they will be read by the same individual. Don’t you think that it is about time that you bring your editorial staff to be in agreement with itself, in order to stop maintaining schizophrenia in each one of us, which, for a “reference paper”, should not be part of the goals ? (…)

I could have added that most often ads carry a message totally antagonistic with the articles written otherwise. I will illustrate this purpose by an example chosen in another field, but that will help to undertand what I have in mind: it might very well happen, on TV, that several ads for sweets or junk food follow a documentary on obesity ! Understands who might, then….

How many journalists discuss climate change?

To my opinion, too few ! We will see that actually information is very concentrated: regarding climate change, as for any other topic, a couple ten to a couple hundred people “make the news” in France.

As exposed above, France has about 35.000 journalists, but all will not include climate change into the information they manage, of course.

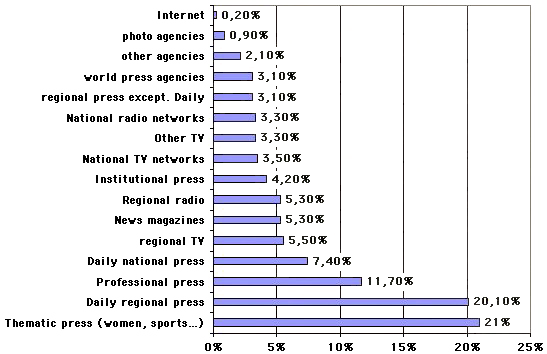

Breakdown of the journalists by media in 2000 (30.325 journalists overall).

“Thematic press” designates (wo)men magazines, TV programmes, magazines on sports, cars, computers, etc. “Professionnell press” designates papers aiming at a given profession (car manufacturers, wine producers, etc…).

News magazines are weekly or monthly publications, containing general information.

Source: Les journalistes français à l’aube de l’an 2000, profils et parcours, Devillard & al., Editions Panthéon Assas.

On this total, about a fourth only will work in a media aimed at the general public and that might adress climate change sometimes: world press agencies, national radio or TV networks, news magazines, national daily newspapers, and a couple of specialized magazines (mostly scientific vulgarization). We might add a couple of journalists in the regional papers, but they probably amount to a few handfuls, and for the rest climate change is generally not a hot topic for women magazines, TV magazines, or even car magazines….

If I judge by the general media I know, it is reasonnable to say that among the editorial staff there are 1 to 3 people in charge of environnement issues, should the case arise 1 to 2 journalists in charge of sciences, and that’s the end of the bulk of the team that deals with climate change. As the total editorial staff generally amounts to a couple tens of journalists, there is about 5% of the team, in rough figures, that follows more or less actively climate issues. Such a proportion, applied to the total of 6.850 french journalists working in the general media, results in about 350 journalists that sometimes cover this issue.

But 350 journalists do not result in 350 independant points of view: haven’t you noticed that the news are about the same in any paper for a given day (or week) ? Indeed, except – sometimes – the “major” national media, the other media (regional ones, in particular) generally get the “non local” news through a press agency (AFP, Reuters, AP..), or through a press release – the same one for everyone -, or…. through reading another paper (or listening to the radio, etc). It is therefore not unfrequent to read an article in a regional paper which is the exact carbon copy of an AFP wire issued the same day, or the previous one, just as it is not rare to see various papers offering about the same article, close to what is contained in a recent press release of “someone” (a major company, a ministry, a movie star…). Well quoting a press agency is quoting another journalist: it is, by definition, second hand information.

It is also pretty frequent to see medias quoting each other, which brings in another intermediate step in the transmission of information, and each of us knows that after 3 or 4 intermediate steps, what we finally get might be pretty far from the original information ! In the same respect, it is not rare to read a book in which the author quotes a media, so that when another media will quote the book, it is equivalent, with the additional step of the author of the book, to the previous case: it is a journalist that quotes one of his(her) colleagues, and we get two points of view that are bound together.

As a conclusion, we might say that there are, in France, about 300 journalists for whom climate change is part of “usual business”, that is1% of the journalists currently operating in the country, and besides only a fraction – that I can’t estimate – of this amount has access to primary information, the rest quoting their colleagues.

Is the press really independant?

Well, ask any journalist, and…you are sure to get a different answer from mine ! Of course, media are not independant, and that also influences the treatment of information:

- a journalist is not independant from the amount of space (s)he has to express him(her)self, or interview someone, or grant chronicles or readers’ letters. On the web (like on this site, for example), length is not a problem: the only practical limit to the amount of information I can spread is the courage – or the available time – of the reader, or my failing inspiration. But when a journalist is granted the fourth of a page, and not a single line over that, or 30 seconds on the air, and not one more, it definitely influences the amount of information that can be spread. In particular, this scarcity of available space heavily leads to suggest binary conclusions: things are good or bad (regardless or their magnitude), clean or dirty (ditto), etc, and nuances are hard to find. May we consider that a journalist is “independant” when (s)he is forced to offer reducing conclusions because of a lack of space, even when (s)he made the effort of performing a thorough investigation ?This same room constraint leads to the fact that when a big mistake is exposed in the paper with 7654 signs, it is never possible to obtain 7654 signs to publish the correct information when the mistake is acknolwledged (if it ever is), so that everybody will keep in mind the initial mistake, except for those that will have noticed the little correction published “in a corner” 3 days afterwards. And in the domain I know (energy and climate change) the press is far from publishing a correction for every initial mistake !

- a journalist is not independant from the delay (s)he has to do his job. When the said job is to be done with a couple hours’ notice (from the morning to the evening, for example), this inclines, except one is the best expert ever on a given topic (and even so…), to make a poor job: it can deprive of useful information sources (for example experts that are not available in the next minute) ; it prevents one from documenting oneself thouroughly, or from getting extra explanations when something is not clear or incomplete ; it can lead to consider as essential the only aspects on which it was possible to work, etc.

- a journalist is not independant from “advertising money” : one can say whatever one wants, there is obviously a limit to the amount of biting you can perform on the hand that feeds.

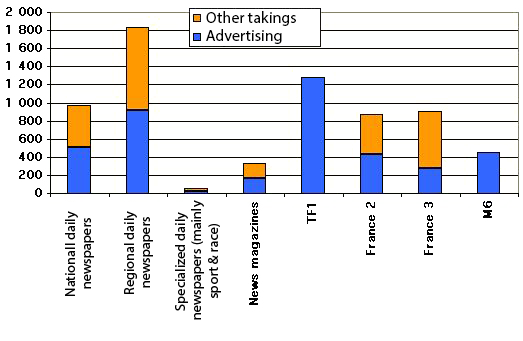

Breakdown by nature of the income of various categories of french media (in million euros, vertical axis).

One will notice that advertising represents at least half of the revenues for the majority of the prominent media (even for the so called public TV !), except for the smallest TV network – state owned – France 3 for which advertising represents “only” 30% of the total.

The cumulated audience of TF1, France 2, France 3 and M6 is over 80% of the total TV audience in France (pay TV, cable TV and minor networks represent the rest).

Unfortunately I do not have figures for state owned radios (for private radios it is not hard: basically their income is 100% advertising !).

Source SJTI (quoted in “Les journalistes français à l’aube de l’an 2000, profils et parcours”, Devillard & al., Editions Panthéon Assas.) ; reference year 1998 for the written press and 1999 for TV.

There are two conclusions to draw from the fact that advertising represents more than 50% of the income of most prominent media.

- As advertising income is proportionnal to the audience, and as any media boss tries to keep money pouring in, any media significantly depending on advertising money is hence obliged to have a content that pleases the audience (Tocqueville already said that, so it’s no news !). Can a media be “independent” when, in first approximation, it cannot say very often things that don’t please the audience, even though it feels like it ? Well, things that might not please the audience, when solutions to climate change are named driving less, heating less, flying less, eating less meat, and buying less manufactured goods, there are plenty!

- Climate change being one of the consequences of the modern mass consumption lifestyle, wishing a firm action against this process implies, for a part, to question the perpetual increase of the material consumption otherwised encouraged by ads. To what extent is it possible to suggest frequently this conclusion in any media that heavily relies on the money of hypermarkets, consumer goods manufacturers, plane companies, or car manufacturers ? To be even more insistant, I have a couple of first hand testimonies that show that people in charge of ads definitely influence what it is possible to say in a media. Is independance still a pertinent word then?

As a matter of fact, it seems to me that, as journalists are generally fast to claim for transparency for the others, they should also comply with this claim and clearly expose who exactely pays them. In this respect, I would consider normal that any media that relies on advertising for more than an third of its income publishes every year the name of the 20 largest contributors to advertising money. Anyone could then draw his own conclusion of the “indpendance” of the said media when the subject covered is more or less related to the activity of one of the ad providers. And if the claimed independance is really there, what is to be feared that would prevent doing so ?

- a journalist is not independant from his(her) initial training :

- Even though I might seem insistant, a diploma in philosophy or french litterature does not necessarily help to understand magnitudes (it does not prevent from being comfortable with figures, but offers no warranty). Well, in this climate issue, the Devil often lies in the magnitudes: if all oil and nuclear plants in France can be replaced by 3 windmills, obviously the conclusion will not be the same than if a couple million windmills would be needed to do so.

- In the same respect, when a journalist does not have any technical background on a given subject, and thus does not know where is “the truth” (the technical one, of course), his(her) natural tendancy will be to do just like a judge: (s)he will ask to all people that offer an explanation what they think, and will be very tempted to mention both explanations, implictely presenting each one as possible, wheras it might well be that one of them is not compatible with the world as it is.Another induced effect of this way to proceed is that, if the same room is allocated to each point of view, the reader – or the audience – will consider, “seen from the outside”, that both explanations have supporters in equivalent amounts, and that both persons interviewed are equally qualified to give an opinion, when it might well not be the case when “seen from the inside” (and this hapens sometimes for climate change).May we say that such a journalist is “independant” if (s)he voluntarily puts forward improbable explanations, or presents as legitimate someone that is not, or should we rather say that (s)he is perfectly dependant of his(her) lack of background or personnal ability to judge ?

- a journalist is not independant from his(her) opinions. These opinions have no reason to have been based on better information than that available for anybody else. Before being a journalist, our friend got information as everybody else: by reading the paper ! And even after the beginning of their professional life, a significant fraction of journalists keep informing themselves by reading the paper…..The existence of personal opinions necessarily influences the selection in the available information, the selection of the indivuals that will be interviewed, or the number of signs that will be granted to each information, hence favourizing – more or less conciously – a personnal point of view (so that media, actually, do not provide information but rather opinions). Nuclear energy offers plenty of wonderful examples of this kind of behaviour: 20 people dying in the explosion of an algerian refinery, or a firedamp explosion killing 30 ukrainian coal minors will lead to a short mention on the side of a page, while anything happening in a nuclear plant without even anybody injured (like Three Miles Island) might remain in the frontpage for days (Three Miles Island remained for much longer). Just the same, avarybody knows, in Europe, that Germany decided – through a vote in congress – to “pull out from nuclear”, but who knows that Switzerland organized a referendum (which is much more democratic !) in may 2003 asking whether nuclear energy should remain a component of electricity production, and that two thirds of the population voted in favor of keeping it ? What reason can we give to this difference regarding the coverage if not that “some informations better correspond to the world as it should be”, according to the journalist ?

- a journalist is not independant, either, from the opinions of his(her) boss. Here again nuclear energy will be a useful source of examples: I own 3 testimonies, originating from 3 journalists of first rank media, explaining that it was not possible to put forward the advantages of nuclear energy in their media, though they would have wanted to do so (fear they not, I will bring the secret along in my grave !). How does that comply with “independance”, exactely ?

Is it very annoying to know that, in fact, a journalist is no more independant than anybody else, whatever (s)he says (or whatever the paper manager says, rather) ? Actually, no: one just has to know it (and anyway it would be senseless to wish that all journalists had no boss, no opinion, and no training !).

The good question, still, seems to be the following: why on earth are journalists perdiocally claiming an independance that does not mean anything ? Rather than boasting such an independance that exists nowhere, no more in a media than in any other place, it would be a much better move to be transparent, that is clearly expose what opinions are supported and why, and where the money comes from (because nobody lives out of love and fresh water, as we say in French). The audience will then judge by itself what degree of credibility should be granted to the news !

What recourse is possible when there is “nonsense” in the paper?

Suppose that I read, in a paper, something contrary to well established facts (for exemple that climate change has been studied by science for the last 20 years only, when many results have been published much earlier), or a perfectly foolish information, in the way that it violates the laws of physics, or is totally mistaken regarding the known magnitudes (for exemple that planting a couple trees is significant to compensate for the world human emissions). What possibilities exist that guarantee that the correct information gets eventually published afterwards ? Well, none. There is no warranty that a false information will ever be corrected in a media if nobody in particular is targeted.

If a journalist says (or writes) “Jancovici is an asshole”, or “Jancovici is a big liar”, I can take legal action if I deem it useful (actually I doubt it !) and, as the case may be, there will be a correction in the media. But if a journalist writes an article in which (s)he explains that the scientific community as a whole is incompetent, lying, and sold to a UN plot (like what can be found in an article of the Wall Street Journal I discussed), or more generally if the purpose does not target a particular individual, but a scientific truth as a whole, there is no formal recourse to prevent him(her) from doing so:

- As no-one is nominatively designated, suing for defamation is not admissible,

- Of course, some readers might protest and write a letter, but as it is the paper itself that will decide, in a sovereign way and without any possible appeal, whether it publishes or not a given letter, there is no warranty that the correct information will be ever brought to the reaaders afterwards (my own experience, on which I definitively have first hand information, is that since 2000 I have sent about a hundred letters to various media, and only four got published, always partially).

- If the media is a TV or a radio, there is not even room for such corrective action: there is no readers’ section, no specific emission devoted to the correction of the mistakes previously broadcasted: anyone can acknowledge that TV or radio news never include the mention of a mistake in a previous edition (though there are some, of course), not even to mention that I never heard in the news the anouncement of a mistake included in a documentary previously broadcasted ! In short audiovisual media never inform of mistakes included in the information they spread. Interesting….

- Contrary to what exists for various professions (physicians, lawyers, accountants…), journalists – in France at least – do not have a code of deontology, and are not sworn in. A new journalist does not take an oath, in which (s)he would commit to sticking to some basic principles, like systematically having his(her) interviews read by the person interviewed, or systematically making a cross-examination of any information obtained, or never turning a single case into a general rule without proof, etc. There is no internal disciplinary instance either, that could deprive dishonnest journalists of their press card, when it is easy to establish that they systematically spread biaised information (which is of course easier when there is an objective reference, as it is the case for science). A journalist can therefore be a shameless liar for all his(her) professional life without any risks, as long as (s)he avoids to name given individuals ou entities, and provided (s)he does it in accordance with the editorial boss of his(her) paper. I know of two practical cases (it has been explicitely said to one of my friend, or to me) where a paper deliberately spread false information regarding climate change, because it considered that it would be better appreciated by the readers than the truth, considered as too “commonplace”.

What conclusion should we draw from all this?

First of all there is one conclusion that we should not draw, in spite of all that is exposed above, which would be to consider that media are “all rotten”, and that they voluntarily lie all the time and about everything. Just in France, and just for the general written press, there are more than 500 papers, and it is quite likely that, among journalists just as for the rest of the population, the proportion of those that do what they can, the best they can, with the constraints they have to cope with, is far superior to that of the big fat deliberate liars.

The vast majority of the false conclusions that I saw – but I can’t boast to be a press review on my own ! – derive from an incomplete knowledge of the subjects discussed, a bad understanding of the magnitudes, or an excessive simplification due to the lack of space, and not from deliberate dishonesty. Still, “seen from the outside”, that is without any personnal previous knowledge on the subject covered, there is no way to know who works well and who works not so well, no way to know whether the truth, which is what derives from the observation of facts, is correctly accounted for, and no way to know whether the points put forward are those that one would have also highlighted if one was “in the journalist’s seat”.

But a first conclusion must be drawn from all this: never take an information in the general presss for granted. The name is not a warranty: I have already seen the most awful information in the Wall Street Journal, in Le Monde, or on Arte.

A second conclusion, which is a major one, should also be drawn: the political world, that gets the bulk of its information through reading the paper, listening to the radio and watching TV, is basically ignorant of what is not in the media. Energy and climate change matters, that have a low – and always excessively summarized – presence in the press when there is no immediate problem, are thus topics for which ignorance is widely spread among those that govern us. I do not know whether we should deplore it, but it is a fact.