Stupid question, your highness: of course not, the economy cannot shrink. Except for unwanted period that should kindly remain as rare and short as possible, the fate of the economy is to grow, and generally we do grow, no kidding !

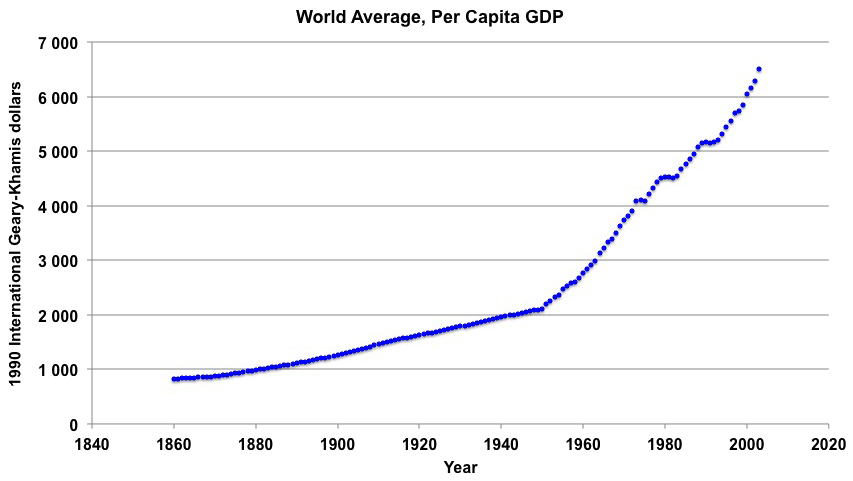

Reconstitution of the average GDP per capita in the world since 1840.

Source : Maddison, 2010

Growth of what, by the way?

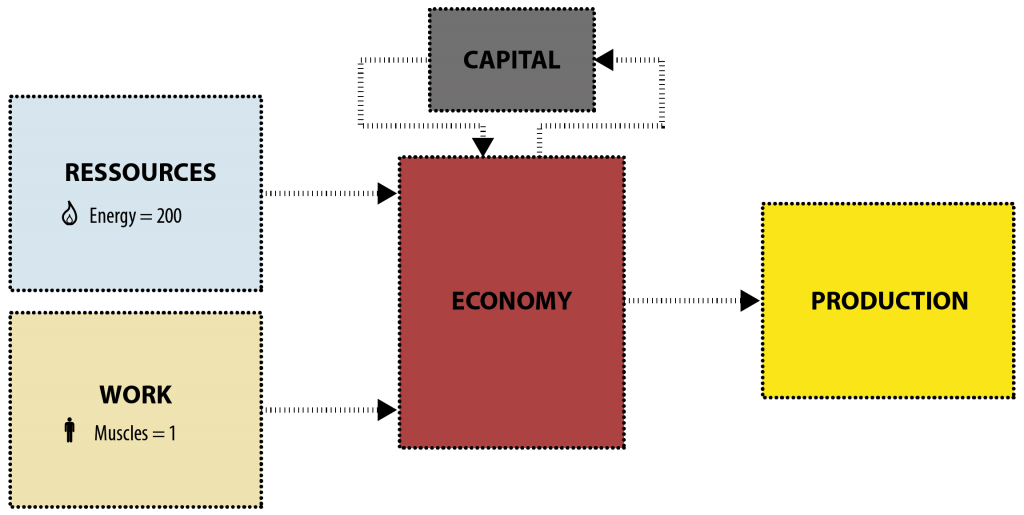

That any sound economist considers that growth is the normal fate of the economy, that’s obvious. But, by the way, what is growth exactely ? When the word “growth” is used, it generally designates, even though nothing follows, something very precise: the increase, year on year, of something that is called the Gross Domestic Product, or GDP. This GDP has itself a precise defiintion: it is the “final production of resident productive activities”. Well, that is something ! If we go step by step, here is a way to translate that into something we can understand:

- the “final production” designs products and services that are used by a final consumer. The final consumer is any individual that uses the good or the service for his own use, and is not going to incorporate it into another production that is going to be sold or transfered to a third party. For example, if I buy an apple to eat it myself, I am the final consumer for that apple. But if I buy an apple because I am a manufacturer of apple pies that I will sell, of if I am a local grocery store, buying apples to resell them, then I am not a “final consumer” for that apple. This “final result” thus designates all what economic agents (individuals, but sometimes also companies, administrations, not for profit activities, etc) consume for their own use. It includes both consumer goods and capital goods (cars, houses, etc), and stock variations.

- this “final result” must come from a “productive activity”. In physical terms, production is actually “transformation”: a car manufacturer is definitely a productive activity, but it does not create cars from vacuum. It assembles bits and pieces coming from elsewhere, and is in fact a “transforming activity”. You have incoming bits, are you transform it into outcoming onjects that are different. And if you go up the supply chain, you will realize that all the activities that took place before are also transforming something into something else.”production” could then include all transformations that are man-made. But actually a “production activity” will be, most of the time, restricted to a “commercial activity”, because it is the only case in which it is easy to measure the result: production is going to be valued at… the selling price ! It seems obvious, but this simple statement is another way to say that in many cases measuring the result is a head-breaking issue. Indeed, how do you value productive activities for which there are no sales ? It can include education (in many countries in the world elementary schools do not send a bill when your kid goes to school), health (same remark), military activities (obviously ennemies don’t receive a bill after they are killed !), and more generally all that civil servants do for the community without getting directely paid by the user of the service offered.Still, all the above mentionned cases do not correspond to the most puzzling situations, because some monetary exchanges took place: the physician and the professor got paid by someone, and it can be used as a base for valuation of the service. But sometimes some services are exchanged without any monetary counterpart (like I help my neighbour to to paint a room and do not ask for anything), and then accounting for this production is even more difficult.It even happens that something is produced and not exchanged.The latter includes all people do for themselves: vegetables coming from one’s own garden, cleaning or fixing at home, all time devoted to kids, etc. In all this cases, the production is genrally invisible in the GDP (no echange, no accounting !). And to conclude this comment on “production”, the action of man is necessary: the fish that naturally grows in the ocean is non-existent in the GDP until it is fished and sold, whereas the fish raised in a farm is accounted for in the balance sheet of the farmer, and therefore appears in the GDP.

- And at last the productive activity must be “resident”. It means that the production must physically take place within the borders of the country, no matter who owns the production unit. Whenever a company changes owner, it doesn’t impact the GDP.

And I was about to forget: GDP is associated to a timelentgh, most frequently a year (but trimestrial data is sometimes available).

As mentionned above, the “production” that is accounted for in the GDP cannot appear by itself. Anew, tree growth and fish reproduction are not in the GDP… except if it is the result of a human action, leading to an exchange with a monetary counterpart. One then immediately understands that the same good can be, or not, in the GDP, depending on the context.

This aggregate, that we now consider to be the Graal of all indicators, is in fact a convention among many others, representing only part of the physical system that our production relies on. It counts what we create but not what we destroy in the creation process, with the consequence that worshiping that indicator is already leading us to growing problems, after having lead us to growing improvements for more than a century. That conclusion derives from a very simple fact: the economic system needs… resources. So let’s take them into account and see where we go !

A big ball 13.000 km in diameter, and us

We human beings are a lucky bunch. When we did appear on Earth, something like one hundred thousand years ago, we instantly benefited from no less than 15 billion years of hard work of Nature. Ages before the stock market era, and without ever asking any bonus for it, Nature did a number of things without which we would not be able to pay any bonus today !

- Nature’s job began 15 billion years ago, with the Big Bang. Its first task afterwards was to create a first generation of stars, with the only available nucleus then, that is protons. In the course of billions of years, these primitive stars have created, by successive fusion, all the elements of the Mendeleiev table that we now have at hand.

- Then, after several billion years (say ten, that is the life expectancy of the Sun), some of these stars have ended their life in gigantic thermonuclear explosions that have scattered into space the “heavy” elements that appeared during all these years. This resulted in the formation of (very large !) interstellar dust clouds,

- The first generation of stars did not use all the possible fuel: a lot of hydrogen remained available to lit a second generation, to which the Sun belongs. And the clouds that resulted from the “death” of the previous generation, after drifting in space, have sometimes been attracted by newly born stars. In such a case, all or part of the cloud starts to orbit around the star, and the dust undergoes – because of gravitation – a contraction process, first forming discs, then stripes, then… planets. And so was born the Earth, about 4,5 billion years ago,

- After various formalities, such as adding an ocean (whose precise origin is still an object of scientific debate), and an atmosphere (most probably created with massive emissions of CO2 from the first volcanoes ; knowing that the heat accumulation that creasted lava and enables volcanism is a consequence of natural radioactivity, we eventually owe the possibility to breathe to radioactivity, isn’t it funny ?), serious things can begin: life creation. After 4 billion years, the remote descent of primitive life includes tens of millions of species of viruses, bacteria, plants and algae (some of them having radically changed the compoition of the atmosphere), animals, and other curiosities that make our most creative artists mere jokers.

And then we come, appearing in this environment that was obviously only waiting for us to create a wealthy economy out of all this. Indeed, was is the economy ? Basically transforming natural resources into “something else”, and nothing more… In order to get where I want to go, we are now going to split the result of these 15 billion years of hard work of Nature in two categories of “natural resources” (actually all resources are natural !):

- those that cannot be renewed at all, and for which we have an endowment that has been given once and for all, or those that have such a slow rate of renewing that, in the course of historical times, we can consider that we won’t get more than the initial stock we had at the beginning of the industrial revolution. In this category we will find :

- emerged land, because tectonics is not fast enough so that we can expect to have extra land (or less land) on Earth in significant amounts in the course of several centuries,

- because of what is mentionned above, mountains, plains, caves, aquifers, hills, and a number of large scale things that go with emerged land,

- cultivable soils, that require 100.000 years or over to appear through sedimentation or rock erosion,

- hydrocarbons, that need tens of million years to be formed from oceanic plankton, and coal, that took 300 million years to form from old ferns during the carboniferous era,

- all ores, metallic or not,

- the global ocean, that cannot be exchanged for a new one if it becomes poorly suited to existing life,

- a climate system, well suited to sustaining life on Earth, which is good news,

- the genetic diversity of tens of millions of species,

- and actually so many things that any object that you will come accross today will enclose something coming from this category (metal, plastics, stones, etc).

- Then we will also find resources that get significantly renewed in the course of a century, provided the renewing process is not hindered by human activity. In this category, we will mostly find what directely derives from solar radiation: water that comes from the sky (provided the “climate capital” is not messed up !), plants and animals (provided their genetic capital subsists !), or solar rays and wind, etc.

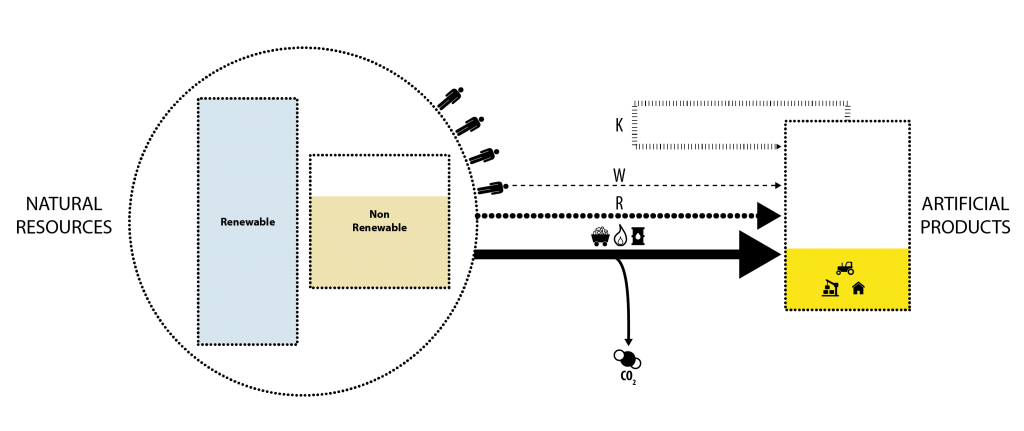

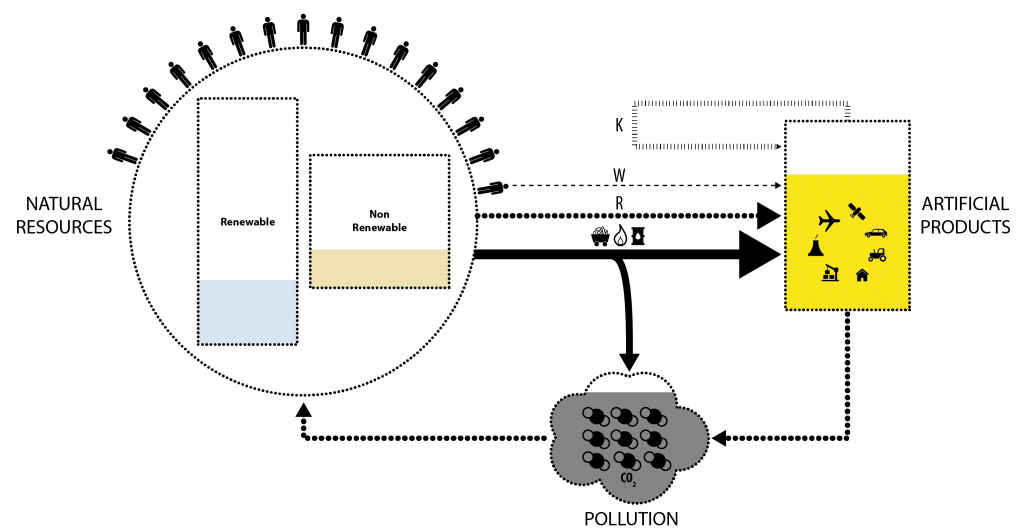

The overall “natural capital” is represented below in a very (very !) simple way.

(Very !) simplified view of our playground before humanity appears.

The immensity of nature is composed of stocks that do not get renewed – or so slowly it doesn’t count – and stocks that quickly renew in the course of a century.

Man is still absent as an agent of a changing world, and thus is not represented here.

And then came production

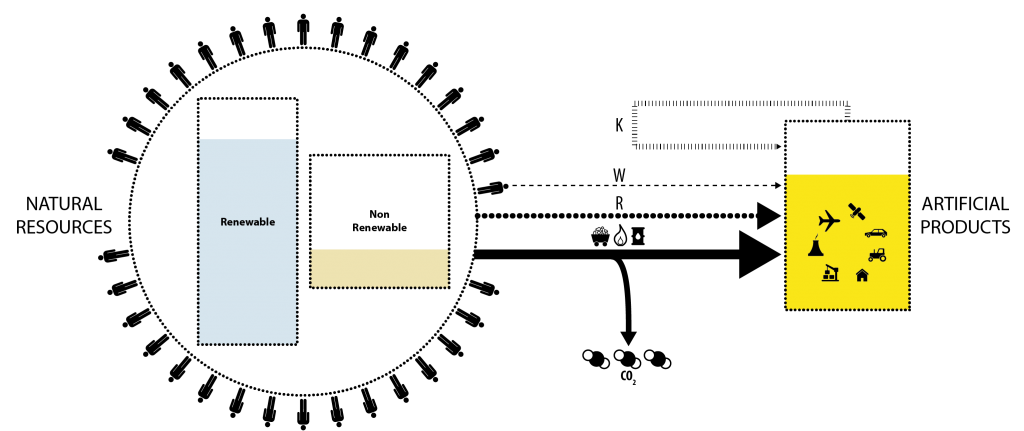

As soon as they took place on Earth, men began to produce. Producing is a very simple activity: it consists in taking “something” from the environment, and transforming it into “something else”. Indeed, from a physical standpoint, be it to build a stone axe or the latest airplane, productive activities are all alike: they transform “natural” resources into “articifial” products.

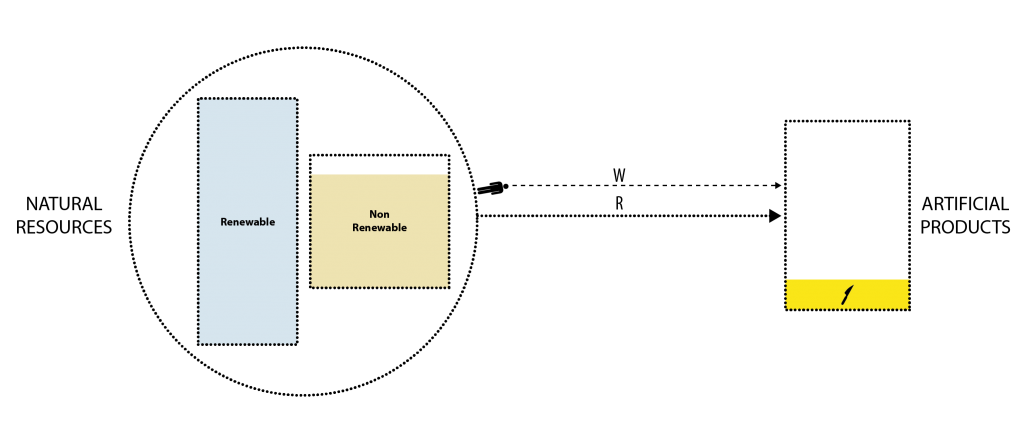

A (still very !) simplified view of the early productive activity of our species.

We use natural resources (R) and work (W) coming from our muscles, a produce agricultural or simple manufactured items (a knife for example).

When men where not numerous, the two categories of stocks did not evolve the same way:

- from the first minute we have begun to draw from them, non renewable stocks have begun to deplete. Of course, our early activity did not trigger any worrying decrease of the stock of silex or of metal ores, but nevertheless the depletion was measurable. When the industrial civilization began, thanks to fossil fuels, the stocks of the latter, that needed 50 million years or more to appear, also began decreasing right away (it does not mean that proven reserves should have decreased right away, for they do not correspond to the oil remaining to extract).

- for renewable stocks, consumption rates of early human productive activities have remained well below the renewing potential (to be precise the renewing flow is more potent that the consumption, and renewing can adjust to the consumption). Therefore the level of the stock did not decrease because of human activity, and the decrease of the stock was not “measurable but very low”: it was nil (the first wood harvesters had no discernable influence on the stock of forests then, and the first fishermen did not modify the global amount of fish on Earth).

Today, all productive activities, in the merchant sphere or not, are still based on natural stocks that we transform into “something else”. We take natural resources (soils, photosynthesis, ores, fossil fuels, water, etc) and we “use” them to produce goods. Some of these goods are labelled “natural”, even though the production process always uses artificial items. For example an apple, considered “natural” by most of us, grows while being protected by “artificial” molecules (even when it is organic: copper sulfate is then used), is transported in an “artifical” car to the store (itself not “natural” !), will most of the time be stored in a (not natural) fridge before it is eaten, etc. To what extent is this apple “natural” ?

Other goods have always been labelled “artificial”, like stoves or trains. But whatever adjective we use to label what we consume, all production uses natural resources to start with. It means a simple thing: no natural resources, no GDP, no matter how many workers and how much capital we still have ! And then, dear reader, just look around you when you read these lines: all you will see is only natural resources, transformed by men or not. Nothing invalidates this rule. Though, didn’t we learn at school that production was a matter of work and capital ? (“only” a matter of work and capital ?). Indeed it is, but it also requires natural resources, and since nobody paid for their creation they are all free in our economic conventions !

And then came the multiplication of slaves

For a very long time, men had to do with the sole mechanical power of their arms and legs to ensure their survival. As a result, the most common way to get more energy than what one’s arms and legs could provide was to enslave other humans (slaves, prisonners, and all that was alike were a good way to increase one’s energy consumption). And then men discovered that they could be helped by extracorporal energies. The first one was fire, allowing to get more heat than with our sole basic metabolism, and then animal domestication, allowing to dispose of increased mechanical power.

But this first stage of human domestication of extracorporal energy is still marginal compared to phenomenons faced by humanity. It is with the industrial revolution that magnitudes are going to change, and then change accordingly the impact of man on his environment. As energy is, by definition in physics, the notion that characterizes a change in the world, when humanity accesses to abundant energy, the individual capacity to extract resources from the environment is going to be multiplied by huge numbers, just as if every indivudual received “energy slaves” that worked for him, only at almost no cost.

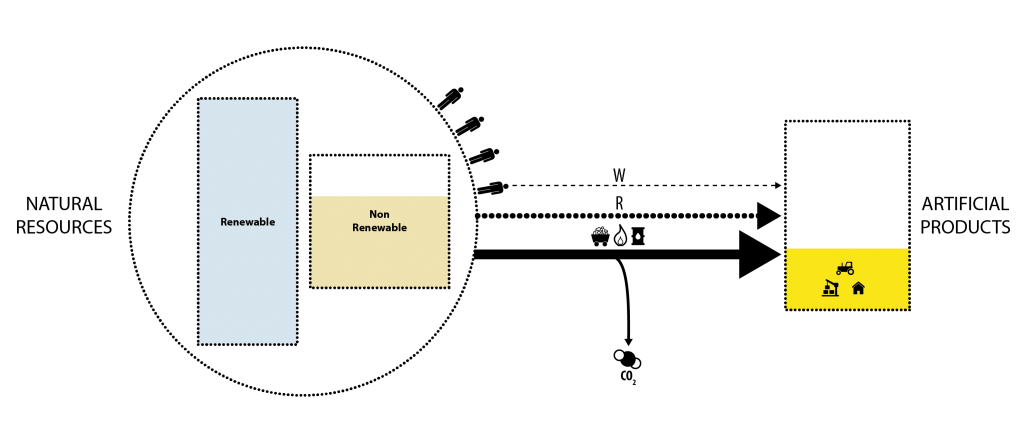

Same diagram as before, only it pictures an increased rate of extraction of resources from the environment, with the help of increased energy use (Coal, gaz & oil), that allows all individuals to work with much more than their sole muscular power.

Energy thus becomes a tremendous amplifier of physical flows produced by men. With energy, men can dig faster in the resource base, and trigger a faster depletion of non renewable stocks. At this point (we are at the beginning of extracorporal energy use), renewable stocks are still used without any rate of depletion.

And then came the capital

What is capital ? Nothing else than good or services that do not disappear when you use them, or at least not right away. Contrary to food, toothpaste, or even a plane trip, that all disappear once you have used them, a building, a computer, or a train can be repeatedly used without disappearing, just as a patent or a brand.

Capital can also be an accumulation of goods that can be kept aside and have a market value for a very long time, and then it is not the use than can be sustained, but just owning them. In whichever case capital is physically very much alike a toothbrush or a paper bag: it is made with resources taken from the environment and work. Any capital asset is just a combination of past resources and work that has the potential to last, and even a software or a patent correspond to this definition.

Therefore, human owned capital would not exist if there were no resources. In a physical description of the productive system, capital is not at all an element wich comes independantly of work and resources, as a number of economists seem to believe, it is just a kind of “savings” composed of past work and past resources, and that helps increase future production. But it is never sufficient to ensure future production, that will always need future resources !

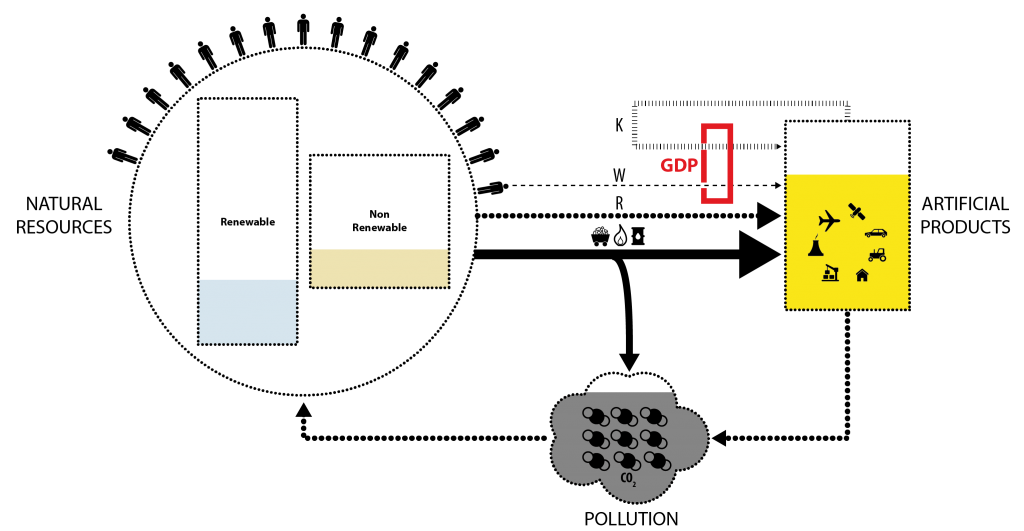

Flow diagram of our productive system now including capital formation.

Composed of past resources and work, it enables to increase the future production.

In other terms, capital formation is an internal loop to the productive system, and not at all something exogenous, that could come from Mars or wherever.

And so there goes our productive system, using resources, renewable or not, and present or past work, to produce goods as essential as coffee machines, or more futile like houses, trains, plates and clothes. With the help of more energy (mostly), more potent techniques, we produce more and more things per indivdual, and at the same time get more numerous (which also has a slight effect on Earth !), and all this results in non renewable stocks getting depleted faster and faster. And one day… our production level also leads to the beginning of the depletion of previously renewed stocks (below). It means that the “renewing potential” of the stock becomes lower than the outgoing flow that we draw from the stock.

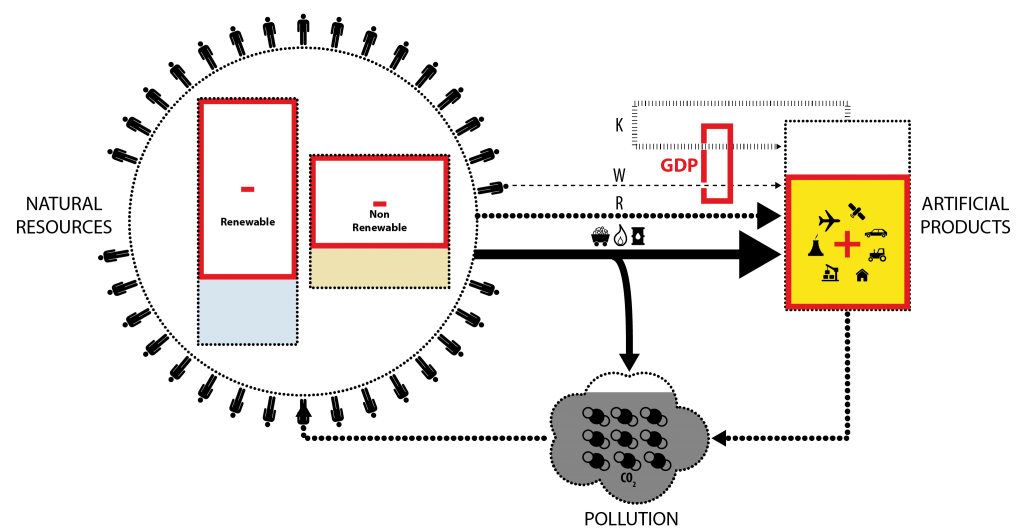

This physical diagram shows what begins to happen when our productive activity becomes quantitatively massive.

Non renewable stocks deplete even faster, and the previously renewed stocks also start to deplete, because the extraction flow we create outpasses the renewing flow Nature creates.

For some “renwable” stocks, depletion has started quite a time ago. For example, the stock of forests has started to decrease after the year 1000 in Europe, leading the fraction of emerged land covered with forest to decline from 80% in the year 1000 to roughly 15% in 1850. A same evolution is ongoing under the Tropics.

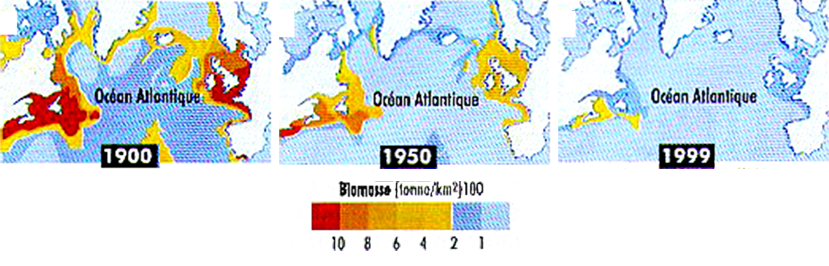

Another stock that was previously renewed and which is now in decline is that of fish, and it has begun since 1900 in the Northern Atlantic (below). The world stock of whales had even significantly decreased in the course of the 19th century !

Evolution of the biomass in the Northern Atlantic between 1900 and 2000.

Source : La Recherche, July 2002

In conclusion, when it grows, our productive activity depletes stocks that it nevertheless relies on, first non renewable, then even renewable ones.

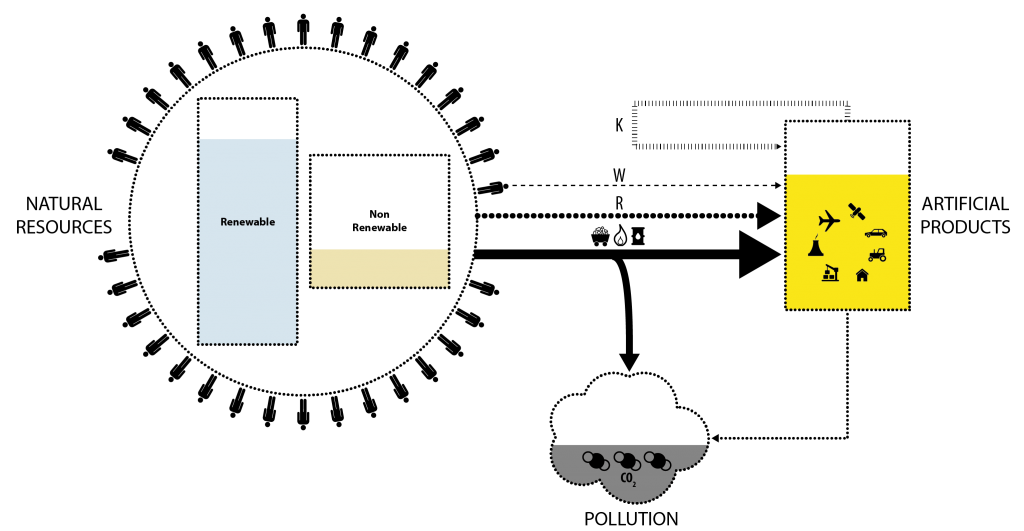

And then came pollution

Up to now, we have limited our considerations to the upstream consequences of our activity (depleting stocks). But our productive activities have another consequence, that will grow along with the flows we generate: it creates what we call pollution. Pollution is nothing else than disseminating in the environment unwanted byproducts of our activity that will degrade the quality of the remaining stocks.

Flow diagram of our activity now including pollution, represented above as a little grey cloud.

All living beings create a little pollution. But here again all is a matter of figures, and, if pollution grows too much, it will one day excede the regenerative capacity of the environment, and lead to an irreversible (or slowly reversible) degradation of the quality of the remaining natural assets, what is equivalent to an accelerated depletion of natural stocks.

Among other examples, an increase of CO2 in the air will lead to ocean acidification, and we can consider that as a “degradation of the initial stock”. Indeed, we have only one global ocean in the world, and if the one we have becomes too acid to sustain certain forms of life, we can’t go to the store and buy another one.

Flow diagram of our productive activity now including the effects of pollution, that is an accelerated decrease of the level of the stocks we found when men appeared on Earth, and that our future productive activitues depend on.

We have now completed a simplified but robust description of the physical flows involved in our productive activities. We can summarize it this way: our activities consist in drawing resources from natural stocks, renewable or not, and transform them with human work (a little) and non-renewable energy (a lot) to increase the “artifical” stocks, while generating pollution that will contribute to an accelerated depletion of existing stocks. Incidentally, what is described here is just reinventing hot water, because 40 years ago a team lead by Dennis Meadows did exactely the same work of simplified but robust representation of the physical flows our economic system relies on, and the conclusions they came to made a lot of noise !

And then came services… “dematerialized”?

But… is all this equally valid for servics ? Indeed, up to now we have considered the economy as if it produced only goods, where a large fraction of what is actually produced is services, fully dematerialized as everybody knows, and that neither use natural stocks, nor create pollution. Or is it that simple ?

Looking at the physical flows will alas bring disillusion: there are no services without matter or energy. First of all, a large fraction of the services (with the nomenclature used in national accounting) consumes a lot of energy, because it is… transportation services (all freight activities, plus passenger travel in planes, trains, buses, boats and taxis, not to mention Branson’s plans for space tourism !). Another service which is very much energy dependant is real estate, because in occidental countries buildings use between 30% and 40% of the energy consumed by the country. And if the only buildings that could be sold were buildings that do not need energy to be built or used (or travelled to), there would not be many sales !

And if we take a closer look at services, it becomes obvious that about none can exist without manufactured products “somewhere else”:

- trade (a very significant fraction of services) cannot exist without goods to sell or buy (which means industries and agriculture), without transportation and seldom without buildings (in which the sales people work), computers, cars and buses to bring people to work, etc,

- bank and finance activities (another large fraction of services; in the UK for example about 15% of the GDP comes from financial services) would not exist without industries to borrow money, construction activities that generate mortgages, and loans to buy cars (and mortgages and car loans represent a very significant fraction of the banking business). It woud not exist either without computers (and manufacturing computers is perfectly material, as it involves metal processing, chemical industries, coal and gas fired power plants to generate the huge amounts of electricity required to manufacture high grade silicium chips, etc), without postal services (packed up with trucks and planes) or telecommunication networks (that are built in a totally material way, with cables, electronic equipment that require the same industries than computer manufacturing, steel and concrete for antennas, and a lot of public works to install it, etc). Whichever way finance is looked at, it is obvious that it is heavily dependant on material flows taking place somewhere else,

- Education (another large fraction of services) would not exist without a lot of spare time to learn, therefore a lot of mechanical slaves to work for us while we study (hard !). Just look where people are able to pursue long studies in the world: you will find many more in energy intensive countries than in places where sobriety is achieved for real ! In purely economic terms, the taxes that allow to pay for public education are derived from our productive activities, and we need a lot of productive activities (requiring a lot of material flows) to have a lot of taxes to pay for a lot of education, which is the logical counterpart of what has been stated just before,

- taking care of kids is one of the first job providers in France (several % of the workforce), and such an activity can only exist if… parents cannot stay at home because they work outside, meaning that they contribute to the productive system that depletes resources. And even to keep children somewhere it is necessary to have buildings, transportation means, food production, diaper production, etc,

In short anything labelled a “service” is in fact a prolongation of agriculture and industry, if not an industry itself, and not a dematerialized alternative to physical flows. The dominant opinion that our industrial societies are “dematerializing” because the share of services is increasing is a myth. A careful look at the fact shows that physical flows, in absolute figures, have never been as high as today, and it is the only things that counts !

And then comes the GDP, that mixes up flows and stocks

But let’s come back to our GDP, that we have defined at the beginning of this page. In our “physical” approach of the economy, this GDP corresponds to something very precise: it is the monetary counterpart of the contribution of human beings to production, that is the value that men have added, through their work or allowances, on top of the value of natural resources, that are otherwise indispensable.

Same flow diagram as above.

The GDP is the measure of the value added by men when going from the resources on the left to the goods and services pictured on the right.

Indeed, as nature does not get paid to supply the result of 15 billion years of evolution, but men do get paid as soon as they work one hour in a commercial system, in the price of any good or service one will find the contribution of human work and revenues (the only one that has been paid for) and not the “natural” part (basically the depletion of natural stocks, and the degradation of remaining natural assets because of pollution), that nobody paid for. If you remember your old (or not that old !) lessons in economy, you might remember that production is supposed to be a function of human capital (K) and human work (W): P = F(K,W). Do not look for the creation of natural stocks in classical economy: they are accounted for nowhere !

And because of this simple fact (that we only pay human beings and not the creation of resources), the GDP is also equal to the revenues of all the people that have enabled the production to take place… from natural resources that have been granted for free. Of course, sometimes we must pay something to the owner of the moment of a given resource, but he is never the one that has created it, nor has he the power to reconstitute a depleting stock ; he is just the owner of the moment. Nobody on Earth can create calcium, iron, or a fish species from a magical wand !

The GDP is thus, by definition, the big pile of salaries, profits, and miscellaneous allowances of men and “economic agents”, which explains why we love so much that it increases. But when we begin to believe that a growing GDP means a global wealth increase, we begin to think wrong.

What is getting richer exactely ? Generally, it corresponds to a net increase in the assets owned, that is the extra possessions of someone, without forgetting to deduct the additional liabilities that person may have contracted to get her new assets. It is not an increase in revenues: if I double my revenues but in the same time triple my expenses, I might increase my standard of living (which is characterized by my expenses), but my net wealth will decrease (I have more debts). There is more: if, with time, my expenses systematically increase faster than my revenues, it is just a matter of time before I get bankrupt.

We see from there that wealth does not necessarily evolve as revenues, but is the result of a balance: it evolves as the difference between what comes in and what gets out. Well, for our global economic activity, that is this famous GDP, the convention has been to count what we create, but not what we use. And we do use natural resources, either as a production factor, or as the result of the pollution we generate.

The price of natural resources in our market economy (for example the price of oil) is nothing else than the paycheck of all human beings that have contributed to extract and bring oil to the end user, but the price for the formation of oil is not included. Oil itself is as free as wind, we should never forget ! When giving a global figure for human activity, we only count things that add up, and never substract anything: the GDP is a turnover without expenses.

Looking at the GDP to measure the state of a country (or of humanity) is like evaluating the good health of a company by just looking at its turnover (or to be more precise its payroll) without looking at its bottom line (or without looking at its assets, which is about the same in the long run). It happens that in a world without constraints, all companies make profits, and the amount is a fraction of the turnover. Looking only at the turnover is then a good proxy in a growing and stable economy. But when the world becomes very unstable, it is not true at all ! If, in spite of an everising turnover, a company is all the time in deficit, it will eventually go bankrupt, because its assets will disappear.

It is the same for our GDP (the equivalent of a turnover): if, though it constantly rises, it generates future expenses – not immediately accounted for – that are greater than the value of the production, growth becomes an illusion. And expenses do exist in our economic system, only we do not take them into account:

- all we draw from stocks that never get renewed, or for which the flow of renewal is greater than the outcoming flow, should lead to some kind of “depreciation of stocks”, just like in corporate accounting,

- all future damages resulting from pollution should lead to some kind of provision for future risks.

A “good” national accounting, then, could imitate a corporate accounting:

- count with a positive value the goods that we have created,

- count with a negative value the resources that we have depleted or destroyed (for example fossil fuels), or the future depreciation of stocks that will be degraded – or destroyed – because of our present activity (as in the case for climate change).

Simplified representation that would be appropriate to know whether we get richer or not.

What we create goes with a positive value (+), and what we have destroyed, now and in the future, with a negative one (–).

Only if the difference between the two is positive can we say that wealth has increased !

This “physical” look at our productive activities therefore allows to understand that the macroeconomy we have designed, omitting the resource component, is now… totally false, and therefore totally inappropriate to make any forecast whatsoever. As long as the stocks where seemingly limitless compared to the activity of our species, it was a good first order approximation to count the depletion for nothing. Without doubt, the value of the first knife made from iron was infinitely greater than the lost value of iron ore used in the process. Ignoring the depreciation of the global stock of iron ore was then a perfect first order approximation.

But two centuries after the first steps of our classical economy, the size of remaining stocks is not tremendous any more compared to the annual rate of human predation. We cannot assume that the value of the natural stock we have used is negligible. Still, we have kept the same “convention of blindness” regarding these stocks ! There is therefore nothing surprising in the fact that we do not see economic crises coming: our representation of the physical system that enables production has become massively incomplete.

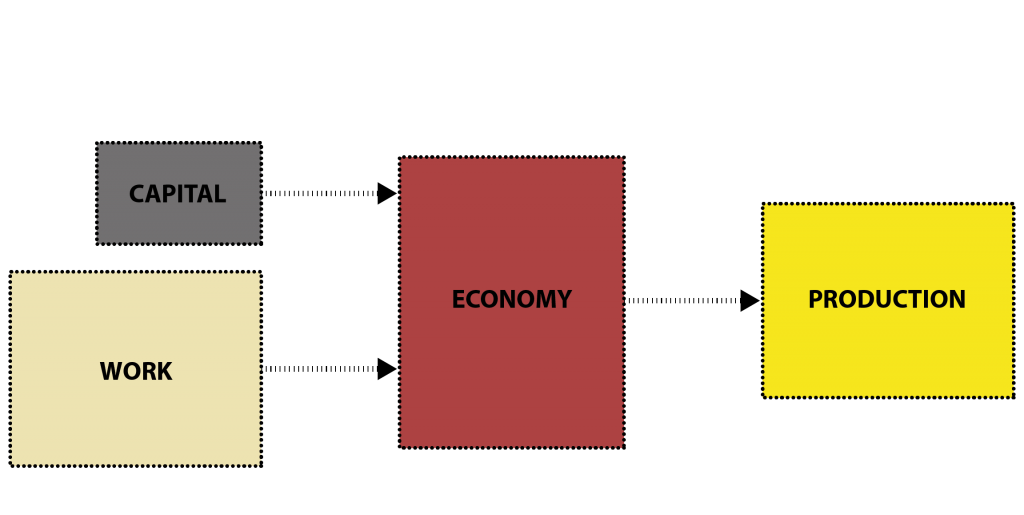

Simplified representation of the economy we learn at school.

Production is a function of capital and work. Therefore if we do not have enough growth, we should inject a lot of capital – the easiest way being increasing credit – and a lot of work – through a decrease of social charges – and we will get more GDP.

The other way round, if we stimulate demand, it will pull production, and generate demand for capital and work. Simple !

Simplified representation of the reality.

External production factors are natural resources and work, and capital formation is an internal loop of the system.

This diagram allows to understand that even if we have plenty of capital and plenty of work, production can nevertheless be constrained… by insufficient natural resources.

The same thing will happen when work is mostly done by machines that use energy, and we do not have sufficient energy. Because in the industrial world, when our muscles provide one unit of energy, machines provide 500 !

As the GDP only measures the flow that goes from natural stocks to “artificial” ones, the faster it grows, the faster we deplete natural stocks, without really realizing what is happening, as economically the depreciation of natural capital becomes visibles only when it hinders the flow that can be derived from it. But as long as the system is configured this way, at some time the residual stock will be too low to allow the GDP to keep rising. When it happens, we will then be far too advanced in the degradation of the physical system to react on time without pain. It is not in a week that we are going to rebuild infrastructure, jobs, organization schemes, economic tools, and substitute resources when possible !

So the funny thing with classical economy is that as long as we do not seek anything else than GDP growth, it is about certain that this quest will lead to the collapse of the very indicator it is supposed to fuel upwards forever…

From the GDP to the “net profit”

Could we count another way ? Let’s give it a try. In 2010, the world GDP amounted to about 60,000 billion dollars. To allow the production of all the goods and services taken into account in the GDP we have:

- used – therefore destroyed – 3,9 billion tonnes of oil, about 2,7 billion tonnes oil equivalent of gas, and 7,3 billion tonnes of coal (source: BP Statistical Review),

- poured into the atmosphere about 50 billion tonnes CO2 equivalent of greenhouse gases, that will contribute to a future climate change that will last at least thousands of years,

- used – therefore destroyed – a billion tonnes of iron ore, and anything from several tonnes to several hundred million tonnes of other ores (from copper to indium, using about anything in the Mendeleïev table),

- deforested between 10 and 15 million hectares of forest (on a world total close to 3,6 billion hectares),

- and artificialized several ten thousands of square km, suppressed a number of living species, turned the ocean a little more acid, depleted fish stocks, melted sea ice, turned an increasing fraction of humanity obese, and I could go on for quite a while with the “dark side of the growth”.

Question: what quantitative values for all these counterparts lead to the conclusion that we are greatly mistaken if we think we got richer on that year ? Because a true wealth increase happens only if the marginal value of the goods we have created in 2010 (that is the GDP of the year) exceeds the marginal value of the natural assets we have destroyed or damaged the same year. The game is undoubtely a profitable one when we “destroy” the first kilogram of iron ore to manufacture the first knife and the first wheel: the added value of what we have created is incommensurable compared to the depreciation of the natural assets we have used.

But, with the increase of the flows drawn from natural stocks, it becomes less and less true. Today, some flows coming from natural stocks are 1,000 to 10,000 times greater than when our species set up the rules of classical economy, that counts for nothing resource formation !

And when the negative value of the depreciation of stocks becomes greater than the positive value of the goods created, we start to get poorer and not richer, though the turnover (GDP) might still rise. And once we cross that threshold, it means that stocks are significantly depleted, and therefore the additional depletion that we will perform the next year will have an even greater negative value, when the extra positive value of manufacturing goods that are already plenty will be even lower. The “loss” is therefore bound to rise as long as we do not modify the physical flows.

Taking natural resources into account can also lead to amusing (so to say…) consequences for corporate accounting. Suppose any company that directely or indirectely emits greenhouse gases (that is almost any company, because owning a car or having an electric device in the office is enough) has to include in its liabilities a “provision for future restoration of the climate system”. It is easy to demonstrate that there is no upper limit to the amount of such a provision.

Such a provision can thus bet set at any level, which means that with an appropriate convention I can offset the profit of any company. With an appropriate set of conventions, not necessarily more stupid than the ones we use today, all the profits of the Dow Jones disappear, and the “net GDP” decreases year after year.

The conclusion of all this is cristal clear: the multiplication of bottlenecks on natural resources, with oil to start with, and a stable climate to follow, will make it harder and harder to pursue economic growth as we know it. And in a “business as usual” evolution, we will not have perpetual GDP increases, but more and more often crises that “nobody has seen coming”, even though we are overwhelmed by available work and capital. Kind of funny, isn’t it ?