Article published (in french) in the January 2003 issue of the magazine “Le Débat” – translated in january 2004

That nuclear power plants hold a place of choice in environment related discussions is obvious. Discussions in this field are of course as old as the technique itself, but since a couple years the prospect of calling more on electronuclear power to help to achieve a fast decrease of the greenhouse gases emissions has given a new impulse to this debate. It is generally the bad sides of the process that are underlined in the media, that often consider that nuclear power plants is a potential source of troubles that are no less annoying thanthe consequences of climate change, and hence that we shoud do without this option to bend the curve of the greenhouse gases emissions.

Arguments put forward to support this position seem sometimes so strong that it is tempting to consider that the case is definitely settled (in disfavour of nuclear, of course). Yet things are not that simple: a careful examination of the inconvenients invoked show that they are either based on inaccurate facts, or valid for many other domains where, surprinsingly, we don’t have the slightest will to object the same way.

The purpose here will not be to bring an inconditionnal support to civilian nuclear (as of today I have never worked directly or indirectly for a nuclear facility), but just to help the reader to see things from a little higher, by inviting one to ask oneself a couple of simple questions one may not have thought of yet. In order to write an article more pleasant to read, I have privileged a presentation with questions and answers, or more exactly “arguments and answers”.

Having 80% of the electricity nuclear produced is a french exception (hence we are wrong and everybody else is right)

It is perfectly exact that the french electricity production is not “in the norm” compared to many other countries. But our country has many other particularities, like producing more cheeses than we have days in the year, of heavily subsidizing our movie industry. Is any “french exception” reprehensible, and should be suppressed in the name of a “principle of uniformity” ? It is amusing to observe that adversaries of “globalization”, that significantly overlap (in France) with the adversaries of nuclear power, ask in another context for the “right to be different”, when the difference is considered here as a major defect !

Actually, merely pointing out the large share of nuclear power in the french electricity production as a good reason to call less on it is mostly convenient to avoid examining things thouroughly: being out of the norm does not mean anything in itself, and hence does not imply that one is right or wrong. It all depends on the circumstances….

Nuclear power is not democratic

It is perfectly exact that no explicit democratic consultation has preceeded the decision to invest in nuclear power in France, in the seventies. But this way of producing energy does not have the priviledge to be the only one in this case: no other one has ever been subject to such a vote. Have the citizens of any occidental country been consulted before starting the “oil civilization” ? Did anyone organize a referendum before building the french dams, or the largest in the world, the Three Gorges dam in China, for which 1 million people will be moved ?

Have the electors of any country in the world been consulted before building coal fired power plants, that emit large amounts of greenhouse gases ? Have the european electors been consulted before the commission published the directive on renewable energies, that is directly at the root of the proliferation of windmills today ? Have the same european electors been consulted before the commission published its directive on the “liberalization” of electricity markets, that will favour short term investments, hence incitate to replace aging nuclear power plants by gas fired power plants, and therefore favour an increase of the greenhouse gases emissions even for a constant consumption ?

At last, let’s note that the entities that operate in the nuclear sector are, in France, state controlled entities (at last for the time being…) and hence that they are much more subject to the “democratic control” than oil companies.

We can also note than a democratic debate on nuclear power taken individually wouldn’t be of much interest, or rather we would soon come to a discussion on energy as a whole, since we couldn’t avoid to discuss also :

- the global amount of energy that we wish to consume (knowing whether we should call on nuclear power or not is a question that has no meaning if we don’t specify the level of desired energy consumption),

- the possible alternatives. Now that the inconvenients linked to the consumption of fossil fuels, in particular, are well known, is no nuclear (and thus a possible heavier call on gas, oil or coal to replace part of it, with more greenhouse gases emissions) more “ecological” than having nuclear ? In 1970, already, the authors of the “report to the Club of Rome” considered that no…

However, there is no reason to dissociate the discussion on nuclear energy in particular from the discussion on energy as a whole. And nobody, among the “official” ecologists – that ask for a pulling out of the nuclear (in France) – has ever suggested a referendum on energy consumption !

And at last, as much those opposed to nuclear power are quick to denounce the “lack of democracy” that went with the setting up of the french electronuclear program, as much they have often tried to obtain the pulling out of nuclear energy without calling for an explicit vote. The way the “pulling out of nuclear” has been obtained in Germany or Belgium remains diffficult to qualify as a model of citizen expression, because the decision resulted from a political agreement, not from a consultation on this subject taken individually.

If we go on looking at what happens in our neighbouring countries, we can even note these amazing facts: the recent decisions that are in favour of nuclear energy have resulted from an explicit democratic consultation (in Finland the decision taken in 2002 to build an additionnal nuclear plant has been preceeded by a year long debate in parliament, and in Switzerland a referendum organized in may 2003 yielded a 60% support in favor of nuclear energy), when the recent decisions “against” in Europe (Germany, Belgium) are either the result of a governmental initiative, or the result of a vote in parliament that happened with no or little debate (Germany).

In France, the Greens – that are against nuclear – have repeatedly tried to obtain a political agreement with the Socialists on this topic, without asking the least that the elector settled directly and explicitely the case. Of course, a classical vote doesn’t allow to draw a formal conclusion : when a candidate promises to help the poor, increase salaries, lower the taxes, improve education, bring happiness to anyone, AND to pull out of nuclear energy, may we conclude that all his electors are against nuclear power if (s)he gets elected ?

To end with a politically incorrect remark, one should refrain from considering that any decision is perfect as soon as it is democratic: Hitler has been put to power in a perfectly democratic way ! Let noone misundertand this remark: I am profoundly democrat. But between being favourable to democracy, and considering that the system is perfect, there is a “slight difference” that Churchill or Tocqueville have so well noticed…

EDF (the french state owned electricity facility) is a monopole (understand: nuclear = monopole = bad thing)

That was true before EDF had nuclear plants ! And many countries had a national monopole with oil or coal fired plants….

Anyway, considering that, when it comes to electricity production “en masse”, an oligopole of private companies is better than a public monopole remains to be proved. The first years of the 3rd millenium did not precisely bring news that confirm this point of view.

Nuclear plants can be replaced by energy savings and renewable energies

This affirmation is qualitatively perfectly exact, even though this “replacement” would be mostly by electricity savings, and for a marginal part only by renewable energies (in France). However, before we can draw practical conclusions from this affirmation, we must complete it with the answers to these two other questions :

- why allocate possible energy savings – that I strongly advocate – to the “pulling out of the nuclear”, and not to the “pulling out of the fossil era” ? Assuming that the “pulling out of nuclear” is a priority implies that climate change or the dependancy on remote – and possibly instable – countries are secondary causes of potential trouble compared to nuclear power. Is it so obvious ?

- are renewable energies more ecological than nuclear energy ?

This second question will probably surprize some readers, but eventually the answer is far from obvious. Indeed, renewable energies are not only virtuous, be it only because they require a vast land use to supply significant quantites of energy. For example, replacing a nuclear power plant by a dam (“renewable”) imposes to drown a valley. Is it desirable ?

Replacing a nuclear power plant by windmills imposes to build several thousands of them AND to build fossil fuel plants or dams for days without wind. Is it a wise choice ? Even replacing nuclear power plants by photovoltaic solar would result today in a large increase of the greenhouse gases emissions, because the production of the said panels is a pretty energy-intensive industry. If, in the long run, the potential of solar energy is important, is it really to replace nuclear power that we should turn to it ?

And at last, as the potential of renewable energies would not allow the least to replace all nuclear production in France, “replacing nuclear plants by energy savings and by renewable energies” would mean, in France, a 50% decrease – at least – of the electricity consumption. Question to be asked to the opponents of nuclear energy (and to which I did not see an anwser very often !): where do we get these savings ?

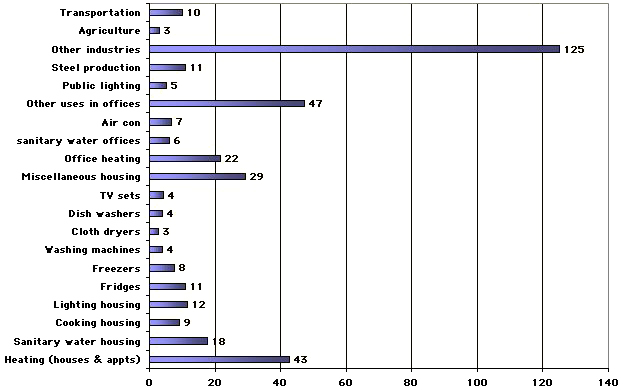

Breakdown of the electricity consumption in France, in Twh (1 TWh = 1 billion kWh), in 1997.

Certainly, “we can” replace nuclear plants by energy savings and by renewable energies. But the good question is: shouldn’t we replace at first oil, gas and coal, which do not have the same usages at all than electricity, by these energies and these – indispensable – savings ?

Nuclear supplies only 6% of the world energy consumption today, so it is not a solution to greenhouse gases emissions

The figure is perfectly accurate : nuclear power supplies only 6% or 7% of the primary energy consumption in the world today, a contribution equal to that of hydroelectricity. As the CO2 emissions (CO2 is the main greenhouse gas) result from the remaining 85%, it is sometimes said that nuclear or no nuclear doesn’t make much of a difference to mitigate climate change. But the same reasoning would also disqualify solar and wind energies, that each represent much less than 0,1% or the world consumption today !

Actually, this argument abusively assimilates present and future, by concluding, without any further discussion, that 6% today mean 6% at most tomorrow, no matter what. Obviously one can’t judge of the potential of a possible solution by uniquely looking at what it is worth today, without any consideration on what it could be worth tomorrow with different hypotheses. Before representing 40% of the world supply, there was a time when oil represented 1%….

More seriously, there are scenarios that envision, to divide the world greenhouse gases emissions by two, a massive call on nuclear energy together with very serious energy savings, and in such scenarios nuclear energy would represent much more than 6% of the world supply. There are no “physical” arguments, today, that could lead to conclude that such scenarios are impossible.

Nuclear energy produces heaps of waste, that nobody knows what to do of

Alas, human activities generate all kinds of waste, and many of them are produced in such quantities that they raise many more problems than those produced by nuclear power plants.

| Type of waste | Annual production in France (in tonnes) | Kg per inhabitant and per year |

|---|---|---|

| Household waste | 21 000 000 | 350 |

| Other municipal waste | 17 000 000 | 283 |

| Ordinary industrial waste (1) | 30 000 000 | 500 |

| Special industrial waste (2) | 18 000 000 | 300 |

| Inert waste (3) | 100 000 000 | 1.667 |

| Animal raising waste (manure, etc) | 280 000 000 | 4.667 |

| Crop waste | 65 000 000 | 1.083 |

| Hospital waste | 700 000 | 11 |

| Radiocative waste of low and medium activity | 40 000 | < 1 |

| Radiocative waste of high activity | 200 | < 0,01 |

National waste production in France, and production per capita, for the main categories of waste.

Notes:

(1) This refers to waste that is not particularly dangerous (but that can nevertheless somtimes degrade): cardboard, paper, glass…

(2) This refers to waste that can require a special treatment : used chemical coumpounds, hydrocarbons, toxic waste, old batteries, etc

(3) this category mainly contains construction waste and rubble

Given the above figures, is nuclear energy really a significant source of waste, even toxic (most “special industrial waste” is), in the whole of our industrial activities ? It might be useful to specify that “nuclear waste” designate only, most of the time, the high activity waste. We should also observe that, depending on the technolgy used, what is a waste in a given context can turn to be a fuel in another one. It is notably the case for plutonium, a fissile material which is generally considered as a waste, but can become a fuel in a fast reactor.

Even in the restricted category of energy related activities, nuclear energy doesn’t have the monopole of waste production: any electricity generation plant produces some ! When electricity is produced from fossil fuels, the waste is called…carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas (the first source for this gas, in the world, is precisely electricity generation). What is preferable, then: getting solid waste (the radioactive one), that we can put into a kind of wastebin (la Hague, a facility designed for the waste treatment), and look after, or having gaseous waste (CO2), which, as soon as it is released in the atmosphere, escapes from any control, and is susceptible to generate global and irreversible consequences ?

When electricity is made with coal (50% of the electricity generation in the OECD countries today), there are also ashes (and various pollutants): delivering with coal the same power than that produced by our present nuclear power plants (in France) would produce more than 20 million tonnes of ash (against 40.000 tonnes of radioactive waste with nuclear plants, that is 2% only, and 200 tonnes of very radioactive, that is a tenth of a thousand of what would be produced with coal).

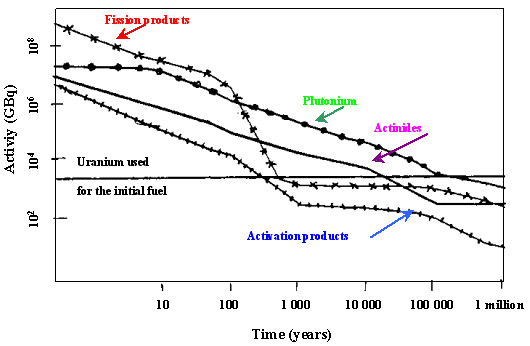

But this waste remains active for hundreds of thousands of years

This is perfectly exact, even if the activity decreases with time, so that the waste does not remain evenly dangerous for all this time, most of the dangerosity being restricted to the first 1000 years: after this period of time, the waste is not much more radioactive than the uranium initially put in the reactor.

Contribution of the various components of a tonne of used fuel to the overall radioactive activity. The horizontal line represents the activity of a tonne of the initial fuel, that is a little below 10.000 Gigabecquerels (1 Gigabecquerel = 1 billion Bacquerels).

The activity of a human being – we all are, perfectly naturally, slightly adioactive – is around 10.000 becquerels, and 1 billion Bacquerels does not represent a particular problem amoung the industrial risks (the new nuclear fuel is manupilated bare-hands). We observe that :

- most of the radioactivity comes from the fission products (such as the various isotopes of iodine), whose radioactivity gets below that of the initial fuel in less than 1000 years,

- it is the plutonium which is main cause of the “long lifetime” characteristic of the waste, but after reprocessing it disappears from the waste, and can be used as fuel in Mox lines, or in breeders.

Source : Rapport du Ministère de la Recherche, “Stratégie et programmes des recherches” ( February 2000 issue – page 183).

Among the industrial waste, there are chemical coumpounds for which the “lifetime” is also very important (persistant organic pollutants for example), if not infinite, and if we confine 200 tonnes of nuclear waste each year (the whole set of french reactors produce yearly 200 tonnes of waste of high activity, and that represent the volume of 4 or 5 cars), in the same time we spread around 100.000 tonnes of pesticides, that have an acute toxicity that might be close to that of nuclear waste, and that have much more impact on the environment.

Parathion, for example, has killed children that had absorbed 2 milligrams of this product, that is an amount close to the lethal dose for high activity nuclear waste (roughly 0,5 mg for an adult). Hence here are 200 tonnes of angerous nuclear waste carefully confined on one side, and 100.000 tonnes of very active chemical coumpounds, some of them being almost as dangerous than nuclear waste, cheerfully spread in the environment on the other side, and yet do we consider giving up abundant meat, whose mass production is the main cause of intensive agriculture ?

At last nuclear waste, in spite of a common idea, maybe because the same adjective is used for all that concerns atomic energy (a nuclear bomb, a nuclear power plant, nuclear waste, just as if we said a chemical plant, a chemical bomb – instead of a conventionnal bomb, and chemical waste – instead of pollutants…), can in no way “explode” or move very far in case of a problem of some kind. A break in the confinement poses a local problem only (radioactive waste is not explosive !), of a much lower magnitude than the consequences of a major industrial accident.

In the end, let’s ask ourselves this simple question: if we have to choose, isn’t it better to prefer a minor problem that lasts for 1000 years, but that we are able to transmit to our immediate heirs in acceptable conditions, to part of a major problem that climate change is, with catastrophic effects that might occur in less than a century, and that we are not able to transmit to our immediate heirs in acceptable conditions ?

Reprocessing of nuclear waste is a costy nonsense

There are many other reprocessing activities that are not immediatly profitable. Using of that argument without distinction would lead to throwing away – no bad joke intended – many other reprocessing operations, though they are attributed all virtues by the same that refuse the recovery of still exploitable elements in the used nuclear fuel.

The cost of reprocessing is not decisive in the production cost of the kWh, and that allows to get a little more energy out of the fuel (but much less than if we used fast breeders). In short, we should reprocess all waste but this one ?

As a private business the nuclear sector can’t survive ; subsidies are a necessary condition for operations

There are three answers to make :

- an answer regarding the argument: the fact that an activity has to be subsidized to exist is not necessarily the sign that it is a nuisance for the community. The railways being built by the state, all train trafic is subsidized: should we suppress trains ?

- Two factual objections :

- the “commercial” companies of the nuclear sector, such as EDF (our national facility which, buying today coal power plants abroad, is less and less a “nuclear” company, what should rejoince the opponents) or Areva, are perfectly profitable, and the administrations, such as the CEA, that do not sell anything, do not have to be more profitable than the police !

- in France, a nuclear plant produces among the cheapest electricity of all production modes in the present economic context..

Nuclear energy is a very dangerous activity

Unfortunately for us, a large number of our modern activities are more or less dangerous. Driving is dangerous (and the risk is not chosen by the pedestrian that gets run over), smoking is dangerous, driking alcohol is dangerous, having chemical plants is dangerous….The good question is: are nuclear power plants more dangerous that the rest of our industrial activities ?

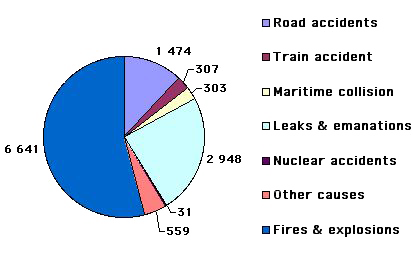

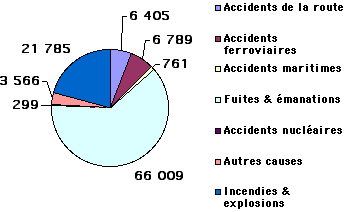

The United Nations Environment Programme has counted the major industrial accidents that happened since 1970. A “major industrial accident” is any event that caused more than 25 deaths, or 125 wounded, or 10.000 evacuated, or 10 M$ of damages. It is interesting to observe (below) what is the breakdown of deaths and wounds byorigin, knowing that Chernobyl is included in the figures, but not mining accidents (China is supposed to have several thousand deaths per year in its coal mines), and not deaths caused by dam ruptures (two major accidents killed more than 2000 people each).

Deaths resulting from major industrial accidents, by origin, beteween 1970 and 1998. “road accident” means that a vehicule is the origin of the problem, but it might be a collision beteween a vehicle and a building. The same remark applies to train accidents.

Source : United Nations

Wounded resulting from major industrial accidents, by origin, beteween 1970 and 1998.

Source : United Nations

You can believe your eyes ! Chernobyl included (which is discussed below), nucear power plants have killed several tenths individuals in 30 years. Meanwhile, refineries, pipelines, and…fireworks factories have killed several thousands, and the chemical industry at least as much. Do we consider, every time a factory explodes or is set on fire, to do without oil or chemistry, every time that a fireworks factory explodes, to suppress all national holidays, and after each Easter, that causes thrre times the deaths of Chernobyl in car accidents (in France alone), to do without cars ?

The good question is therefore not to wonder whether nuclear power plants are dangerous, but whether they are more or less dangerous than :

- our other industrial activities (the answer is no: it is less dangerous than chemistry by far, as the statistics of the United Nations demonstrate),

- other ways to produce electricity by which we should partially replace it if we do without.

For the second question, here is the conclusion of the World Health Organization. It happens that I personnally know one of its former deputy director general, now retired, that I have the greatest difficulties to imagine as being on the payroll of whatever lobby there is, and that would therefore certainly underlined whether the below figures were incorrect. But it is true that nobody’s judgment is infaillible !

| Production mode | Deaths by GW (electric) of installed power and by year, normal conditions |

|---|---|

| Coal | 1,3 to 17 |

| Oil | 1,5 to 11,1 |

| Nuclear | 0,3 to 3 |

Dangerosity of some production modes for electricity, depending on the primary energy used.

Source : Nuclear Power and Health, World Health Organization, 1994

This figures take into account, of course, the exposure of nuclear workers to radiations. Question : is this organization – for which it is not notorious that it is a subsidiary of AREVA, Westinghouse or the CEA – telling us lies ?

But Chernobyl would have killed tenths of thousands of people…

Regarding the Chernobyl accident, the vast majority of the informations that are published are of third hand, if not more: “somebody would have told me that…”. Most of what can be seen on TV or heard on the radio is not coming from physicans or biologists, but from antinuclear movements, that do not publish in peer-reviewed scientific reviews. This situation allows all manipulations, like showing on the TV people affected by various diseases, then declaring that it is a consequence of Chernobyl.

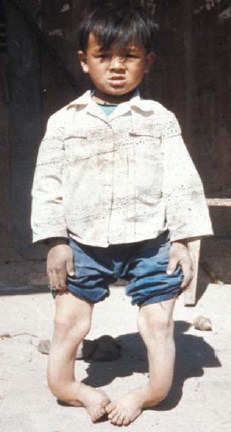

But, as the pictures below will show, all malformations do not come from exposure to radiations: many other causes can lead to casualties or injuries, and what follows comes from… coal.

Hyperkeratosis coming from an arsenic poisoning in China (arsenic is absorbed from coal combustion in domestic ovens).

Source : Health Impacts of Coal, Robert B. Finkelman, US Geological Survey, 2003

Skeletal deformation due to fluorine poisoning coming from coal use in China.

Source : Health Impacts of Coal, Robert B. Finkelman, US Geological Survey, 2003

Combined effect of a lack of vitamin D combined to fluorine poisoning coming from coal use in China.

Source : Health Impacts of Coal, Robert B. Finkelman, US Geological Survey, 2003

To find out what is happening exactely, we must go back to “first hand” informations, that is the papers directly written by the physicians that conducted the epidemiologic studies on the people that received the ionizing radiations as a consequence of this accident.

An epidemiologic study is a statistical study, conducted on a (very) large number of people, that aims at knowing whether there is a visible effect, on the medium to long run, for a cause that does not have any immediate effects, and if the answer is yes, to quantifiy the long term effect. Such epidemiologic studies exist for car pollutants, tobacco, alcohol, or more generally for any substance with a supposed long term toxicity. Such studies are the only way that can lead physicians to conclusions when the effect is not certain (tobacco is a typical example: no one is certain to die from smoking). They generally deal with a very large number ( several thousands at least) people that have been exposed to an agent with potentially harmful consequences, to compare their evolution with that of a reference group, not exposed but otherwise similar in every respect (age, sex, occupation, etc) to the exposed group.

For Chernobyl, the “agent with potentially harmful consequences” is the surplus of radiations received. A synthesis of the results of the numerous studies conducted is periodically done by the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects or Atomic Radiation, a division of the United Nations that can hardly be suspected of being on the payroll of “nucleocrats”.

The lastest edition of the synthesis indicates that the accident caused roughly 50 deaths within a short delay after the accident (mostly among the first “liquidators”, that were essentially firemen), has undeniably caused a surplus of thyroid cancer amounting to roughly 2.000 cases (which have lead to 10 deaths as of today ; it is a cancer that, treated soon enough, can be pretty well cured), and that, beyond these established facts, it is not possible to characterize a surplus of other pathologies (leukemia, solid tumors, birth defects, etc) linked to the Chernobyl accident.

But isn’t this the result of a large conspiracy aiming at hiding the terrible truth to everybody ? I will let everyone judge whether the physicians (because the authors of the studies are basically hospital physicians, specialized in cancer treatment), that have conducted or rewied the tenths of epidemiologic studies quoted by the UNSCEAR are all dishonest traitors….

Let’s go a little further: when the “oil lobby”, or “car lobby”, both by far richer and more powerful than the “nuclear lobby”, have never been able to prevent the same physicians to denounce the inconvenients of car pollution, when the chemical industry, also more powerful – by far – than the nuclear industry, has bever prevented the World Health Organization to publish that Bhopal had caused thousands of deaths, by what miracle would the WHO have been afraid in front of the “dwarfs” Framatome and Westinghouse for the deaths of Chernobyl if medial studies, done with respect to the state of the art, had announced thousands of casualties ?

At last, more seriously, three elements must be kept in mind :

- Only 20 or 30.000 people received more radiations – from the accident – than what one gets – without complaining, in general ! – when one undergoes a scanner examination,

- Cancers and congenital malformations happen “normally” everywhere – and all the time – in the world: Chernobyl or not, a fourth of the french population dies from cancer, and a fraction of the births has always produced abnormal babies. One of my grandparents was born deaf, and I know for sure that it wasn’t Chernobyl (!), and my elderly sister is mentally handicapped, and as she was born in 1960, I also know for sure that it wasn’t Chernobyl. The mere fact of showing a handicapped child on TV does not prove anything: there have always been some. The good question is to know whether there are more of them than usual (the fact that they have all been gathered in a hospital doen’t mean, either, that there are more than usual !), and so far the answer of the physicans is: we are not able to conclude anything of this kind from the availabler data.

- After Chernobyl, Ukraine experienced a major recession, with all kind of negative impacts on health, among which a decrease of the life expectancy. The situation is similar (decrease of the life expectancy, increase of morbidity) can be observed in the former USSR, where no nuclear accident happened: the mere observation of an increase in the number of deaths is not sufficient to attribute the exclusive responsibility to Chernobyl, or to any other isolated cause by the way. Are we also going to consider the orphans that pack the orphanages of Romania as children of Chernobyl ?

Still, nuclear industries poison populations with radiations

According to the World Health Organization, here is the breakdown of the ionizing radiations that we receive each year, knowing that the annual dose received is, on average for all earthmen (and women !), 3 mSv (the Sievert, Sv in short, is the unit of received dose for the ionizing radiations), but can vary between 2 and 50 mSv depending on the place on earth, without any observed sanitary consequences.

| Origin of radiation | mSv/pers/year | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| Radon (radon is a radioactive gas that comes - perfectly naturally - from the disintegration of radium, and that we all inhale in small quantities) | 1,3 | 42% |

| Radiations of medial origin (X-ray exams, cancer cures...) | 0,6 | 20% |

| Eaten elements (mostly potassium 40 included - naturally also - in food) | 0,5 | 16% |

| Cosmic rays | 0,4 | 13% |

| Internal radiation | 0,2 | 6% |

| Other artificial origins (various mining industries, atmospheric fallout of military atomic tests, some instruments of measure, some industrial processes such as X-ray exams of seams ...) | 0,1 | 3% |

| Of which electronuclear plants | 0,01 | 0,3% |

Source : WHO

Same question as for Chernobyl : do all physicans tell us lies ?

Chernobyl has polluted the environment for centuries

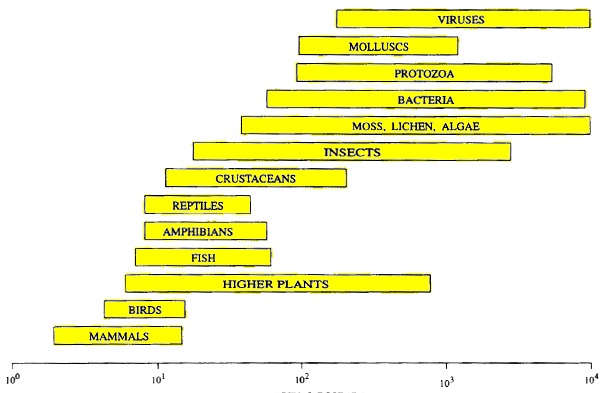

We must know that what we call the “environment”, that is basically what is not mankind, is generally much less vulnerable to radiations than our species : a mortal dose for us will hardly disturb a plant, a micro-organism, an insect, a lizard, or even certain mammals: man being one of the most evoluted species, it is also one of the most sensible to ionizing radiations.

Brackets of lethal doses (in Grays) for various groups of species.

A dose of 1 Gray is equivalent, depending on the nature of radiation (neutrons, alpha particles, etc) to an dose-equivalent of 1 to 20 Sieverts.

Source : UNSCEAR

Besides, if an animal becomes sick because of an irradiation (what does not make it heavily radioactive !) or has a birth defect for the same reason, it will have the fate of any weakened animal in the wilderness: it will be eaten. A consequence that is considered as unacceptable for us (the death of 2% of the population, for example) will be hardly noticed in the environment: an extra 2% death rate, for a given year, for animals that are not threatened (rats, deers, earthworms, boars, or whatever) is of striclty no consequence after a couple years.

What is a problem, in fact, and is generally designated through the expression “contamination of the environment”, is not the long terme damage caused to the surroundings of the reactor (when a forest fire burns trees that are several centuries old, the time duration needed for restoring things as before is not instant either), far less important than what we commonly think, but the fact that the local fields have become improper for an agricultural use: plants still grow very well, because they are not disturbed by the radioactive surplus, but they sometimes enclose (in a random way, because it can heavily vary from a place to another) an amount of radioactive isotopes (caesium in particular) that make them improper for human consumption with the standards that we have established (and knowing whether the standard is justified from a sanitary point of view is a long debate, sometimes…).

However, and even if this statement will shock some readers, the Chernobyl accident has paradoxically also had a positive consequence for the environment, merely by leading to the evacuation of all men in a radius of 30 km around the plant, a zone that became uninhabited since then. Indeed, the suppression of almost all human presence (man is by far the first predator of the wildlife) more than balances the surplus of radioactivity that the accident has generated near the plant ! Some countings done on animal populations seem to indicate, for example, that many species now thrive in the “forbidden zone” much more than before.

Though it is not politically correct to state things as such, we could say, without exagerating much, that Chernobyl converted, by force, cultivated land (and a city) into a nature reserve (a “nature reserve” is indeed nothing else than a place where men is kindly asked not to settle, and to move on the tips of his feet). The level of radioactivity is definitely higher than before the accident, but as it is exposed above it does not disturb the tremendous majority of the living beings that exist there.

Of course, 130.000 people had to be moved to get there, but the Three Gorges dam in China, built to take advantage of a perfectly “clean” and renexable energy, required the move of more than a million people, and will anihilate all non aquatic life (and not 2%) at the place of the future reservoir, that will occupy roughly 50.000 km2 (against roughly 2.800 km2 of “forbidden zone” for Chernobyl). So, where is the truth….. ?

With nuclear power plants, atomic bombs are not very far

This argument is factually true (in the sense that it is possible to get some military material out of some types of nuclear reactors, Chernobyl being precisely one of them) but it profoundly misses the bad side of human nature : the majority of the countries that have nuclear power plants had the bomb BEFORE having civilian nuclear facilities, as it has been the case for many other technologies by the way. The risk of seeing the existing electricity facilities being used to favour nuclear proliferation – that we must absolutely avoid, that I agree ! – is, alas, low: in most cases the stupidity has already been done.

Even today, it remains cheaper and more simple to directly build an installation allowing to produce military grade uranium 235 than building a nuclear power plant to extract plutonium from it afterwards.

Should we then, in the name of a regret, do “as if” we could come back ? Can we really seriously assume that suppressing nuclear power plants would allow to get rid of the atom bomb in the same time ? In the present world, shouldn’t we rather avoid reasons to fight, the depletion of fossil fuel supplies or the consequences of climate change giving potentially so many occasions to do so ?

Should the US – that already have a considerable arsenal – be prevented to call more on nuclear power because it would enable them to have the bomb ? Shoud Spain or Canada be prevented to have more nuclear power plants for the same motives, when both these countries already have plants in operation ? Should we also prevent China, that already has the nuclear weapon, to buid more nuclear reactors ? Well, if we put end to end all the countries that arleadyu have the bomb or existing nuclear power plants, it is more than 80% of the world electricity production which is concerned.

Actually calling massively on nuclear energy in the OECD countries would precisely allow to leave oil and gas to the poorest countries – and often the most instable – where we would not welcome the existence of nuclear power plants (I would definitely be upset if I learnt of the existence of an electronuclear facility in Sudan) while dividing quickly by two the world CO2 emissions, a sine qua non condition to stop enriching the atmosphere in carbon dioxide and thus halt – with a couple centuries shift – the temperature rise.

But, of course, it is always possible to say that the mere existence of nuclear power plants “somewhere” allows a plutonium smuggling and therefore the making of a bomb “elsewhere”. This is true on paper, but actually making a bomb is a long and complex operation, and basing everything on plutonium smuggling from elsewhere would probably be much more complicated and hazardous that setting up an uranium 235 enrichment device. In addition, the plutonium produced by a plant is of military grade when it has not been much irradiated, so that making a bomb requires to withdraw the nuclear fuel from the core very often, what is not at all profitable for electricity production. The risk of seeing bombs appear where we do not wish them exists, but the existence of extra nuclear power plants outside of these countries does not significantly increases that risk.

There is sometimes another argument, more “philosopical”, which consists in saying that any technology that has been designed by the military should never be used for whatever civilian use. In such a case, no opponent to nuclear energy should use Internet, as it is a derivative of Arpanet, that was a network designed for military communications !

Electric heating is a waste

This argument, often presented as “anti-nuclear” in France, is actually not specific to this way of producing electricity: it tends to fight, generally speaking, the idea of calling on electricity for heating uses, explaining that the losses during the conversion of heat into electricity (in the power plant) is too penalizing and that we had better use directly heat at home. If electricity is produced out of fossil fuels, we should definititely prefer to burn these fuels directly in a boiler at home rather that starting by producing eletricity out of them to use this electricity for heating afterwards (the overall efficiency is divided by two when converting fossil fuels into electricity first).

But in France nobody can directly use the heat of a nuclear reactor at home ! The good question then becomes to know whether it is better – from the environmental point of view – to use “nuclear” electric heating, even with a little coal complement and distribution losses, or use “something else”. If the “something else” is fuel oil, gas or coal, french electricity is better positionned. (calculations here, in french only alas)

If the “something else” is wood or thermal solar, it is effectively better to use these renewable sources, but not necessarily to decrease the nuclear electricity production (see above). We might also use this electricity becoming “useless” to replace oil….

Nuclear is a costly industry

What is talking money about ? It is adding a layer of hypotheses or of rules to the real world. So, a price does not exist outside a given set of rules. It exists only for a given social system (market economy, or planified economy), a given supply and a given demand, a given level of technology mastering, a given tax system, and, if the price is partially the consequence of an investment, a given interest rate.

When it is said that something is “expensive”, is it because the raw material is scarce, the technolgy is not tuned, the taxes are high, the interest rates are high, or the demand too important… ? Depending on the answer, it is not the same conclusion that we must draw. To come back to our nuclear, saying that it is expensive doesn’t have the same meaning depending what we are talking about :

- Do we mean that it is expensive for the consumer ? It would be inaccurate, anyway, to say that it is more expensive than other “classical” production modes: over the lifetime of a plant, the electronuclear kWh is among the least expensive and the leat volatile (see energy prices). Let’s note that all renewable energies cost much more than nuclear energy. Is it a valid reason to turn away from these sources ?

- Do we mean than nuclear energy is costly in imports ? When a Frechman consumes one tonne oil equivalent of primary energy (that is a fourth of the average energy consumption per capita), France has to pay less than 10 euros in uranium ore if it is nuclear electricity, but our country must pay more than 200 euros if it is oil (see energy prices). The fact that the consumer pays the same price per kWh for gasoline at the pump and domestic electricity (see energy prices) corresponds partly to the fact that nuclear electricity requires more jobs in France, for the same amount of energy for the consumer, than oil.

- Do we mean than nuclear energy is costly in investments ? Expressed in percentage of the energy consumed, research on civilian nuclear is half as costy as oil prospecting,

- Do we mean than nuclear energy is costly in damages caused to the environment or to the populations ? A recent document published by the european council indicates that the “hidden costs to the environment and the populations” (what economists call externalities) associated to the fossil fuel consumption are way over those associated to nuclear energy.

- And at last do we mean than nuclear energy is costly because of the future dismatling of the existing power plants ? Well this costs is already provisionned in the balance sheet of EDF.

Not only are most of the affirmations regarding the excessive cost of nuclear energy perfectly incorrect, but, once again, the discussion on prices is a secondary one: the discussion on the long term availability of ressources and on the real damages caused to the environment is a prioritary one. Well for both these aspects nuclear energy is rather better positionned than its immediate opponents, able to mass production of electricity. And, once again, invoking costs as a valid argument leads also to disqualify the renewable energies, generally considered as “perfect” by tje antinuclear. So ?

Nuclear power plants only allow to produce electricity

Wind power, hydroelectricity, and photovoltaic solar also, and though all these ways to produce electricity are praised by adversaries of nuclear power (with the exception of large dams, not without good reasons).

I wouldn’t argue, though, that these “energies” have no interest. But why should we turn away from an energy source because it “only allows to produce electricity” ?

Besides, it would theoretically be perfectly possible to use also the heat coming out of the nuclear reactors (presently released in the rivers, the sea water, or dissipated in the cooling towers, which is certainly a pity), if we took the pain of thinking a little harder about what to do with it: nuclear ccogeneration, in a way !

Nuclear energy depends on a limited resource: uranium

This is today perfectly right : the present reactors just know how to “burn” uranium 235, a fissile material. Fission is the “splitting” of a large nucleus, following the absorption of a neutron that makes it instable, into two smaller nucleus, along with the emission of several neutrons and gamma rays. The energy is “enclosed” in the speed of the particles after the fission and the gamma rays.

Uranium 235 – one of the isotopes of uranium – is not very abundant in exploitable concentrations (there is plenty in sea water, but with a very low concentration). With the technology used in the plants now operated, nuclear has resources which are of the same magnitude than oil reserves, but not much more.

But there is not only one nuclear energy: another way of proceeding, much more “sustainable”, would allow to bypass the problem: breeding, that designates a reaction which, in its first steps, produces more fissile material than it consumes. This can be done by using elements qualified as “fertile”, such as Uranium 238, or Thorium 232 (we would then have several millenia in front of us). A “fertile” nucleus needs two neutrons (intead of one) to break up: a first neutron – with the proper speed – makes it fissile, and after receiving a second one it will split just like uranium 235.

Fertile elements are much more abundant than uranium 235: roughly 200 times more for uranium 238, for example, and 400 to 500 times more for Thorium 232. Breeders have other advantages: they allow to “burn” the plutonium coming from the reprocessing of the waste coming from “classic” plants or coming from the disposal of nuclear weapons, and produce less waste than classical reactors.

But as it is technically easier to deal with fissile than fertile materials, and most of all that materials only fertile are not appropriate to make weapons, which historically (and unfortunately) represented the first reason to have an interest into “nuclear matters”, fissile materials have been used in the first place, in spite of the fact that they are far less abundant.

It does not mean that breeders – hence using fertile materials – are out of reach. In France, we had a breeder connected to the grid: Superphénix. It has not been abandoned because “it xould never have finctionned properly”, since the plant delivered electricity to the grid for several years. Of course, it did not function 100% of the time at the first try, and experienced various – but never dramatic – technical incidents, but in research (Superphenix was a prototype) the normal rule is that things go wrong from time to time !

Anyway, whether Superphénix correctly operated or not was not the problem, for its dismantling was a kind of “gift” given to the Greens, that came to power along with the Socialists, and that have always asked for the giving up of nuclear power (surprisingly enough, they are almost never heard on nuclear weapons).

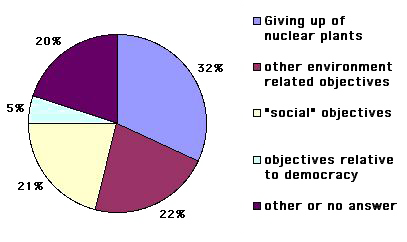

Answer to the following question submitted to the members of the Green party: if your party could obtain just one thing from the present government, what is your preference ?

Otherwise the same polls indicates that 87% of the members of the Green party favour a definitive giving up of nuclear energy within 10 years.

Source : Excerpts from a poll published in the paper Les Echos on January 11th, 2002

Many projects of breeders are studied today, that would call on more modern techniques than those used in Superphénix (which had weaknesses, of course, for example using melted sodium as a heat transport fluid did not raise great enthusiasm…). But will they be launched soon enough to give us the potential they would allow ? Indeed, it is necessary to have several decades, a delay difficult to compress, between the decision to build a prototype, and the connectg to the grid of a commercial installation: in no way can a significant extra call on nuclear energy be set up quickly the day we decide that we have had enough with oil (or coal, or gas).

And in the very long term (but specialists consider it a dream to hope any significant results before 50 to 100 years), fusion, which is also a nuclear reaction, might become operational. It is rather amusing, though, that “anti-nuclear” are much more “anti-fission” (against uranium) or “anti-breeding” (against plutonium) than “anti-fusion” (against tritium), when, fundamentally, these are only different ways of recovering a same nuclear energy (that is that comes from the nucleus). Isn’t fusion perfect, today, basically because it still does not exist elsewhere than on paper ?

A country with nuclear power plants in not defendable in case of war

Let’s suppose that we had no more nuclear energy in France. As no combination of renewable energies allows to produce the same electricity in France (and by far), it would mean that our country would baiscally depend on oil, coal and gas, that all are imported in totality (except 1 or 2% !). Is a country almost 100% dependant on foreign countries for its energy supply a perfectly defendable country ?

Let’s suppose that we increased a little more our greenhouse gases emissions, as “ecologist” activists ask in France, proposing to substitute nuclear energy by gas fired power plants (and that share this demand with a number of eletricity producers and large industries, which is pretty funny), and as the Greens suggested to do at the last presidential elections. Is a country that a climate gone beserk makes inhospitable perfectly defendable ?

And Bin Laden, will you say ? In times of war or of terrorist attacks, it is far more efficient to bomb an inner city or a large office building than a nuclear power plant (or La Hague) if the objective is to maximize the number of casualties, as the comparison between 9/11 and Chernobyl clearly demonstrate. And at last a nuclear power plant is rather more resisting than a “classical” power plant (because of the concrete cover) when the ennemy would be tempted to bomb the plants anyway to disrupt the electricity production.

Thus any centralization of electricity production is a vulnerability factor in times of war, be it with nuclear, dams, or anything else, ans sanitary hazards are not maximal with nuclear energy. The dislocation of a dam, for example,is not necessarily a catastropha preferable to the bombing of a nuclear power plant, and is no less difficult. Should we also forbid dams for this reason, while recalling that they have killed many more people than nuclear power plants so far ? (roughly 5000 people died following dam ruptures, mainly in 2 accidents that occured in Frejus-Maljasset and Larront-Valjonne).

The “nuclear lobby” is opaque and not democratic

This affirmation reflects some kind of reality, but once again things are not as simple as it seems.

In the first place, in France the “nuclear lobby” is not a usual one, as, for example, the lobby of chemical industries, of car manufacturers, or of cereal producers, because, contrary to these cases, where the members of the “lobby” are mainly private companies, most of the actors of the nuclear sector are administrations (CEA), or state owned companies (EDF, Areva). Of course, if, for reasons that I still miss, Areva and EDF are “privatized”, this argument will become invalid ! Then there will be a true “nuclear lobby”.

This is an important distinction : when the “lobby” is made of private companies, it is the money provider for the state, through the taxes paid by the companies, the activity generated, and, sometimes (see the “Enron case”, or the “Elf case”) it is also the money provider of the political parties, when not of the politicians themselves. Such a lobby may well, even if it is cynical, threaten to do business elsewhere, taking along taxes and jobs, when decisions are taken that do not please the companies, and that position gives important possibilities to get an attentive ear.

When the “lobby” is made of civil servants (case of the CEA), it is the state which is the money provider, and the “client”. The “lobby”, then, is more dependant on the political will that decides of its budget, the localization of its activity, and its staff, than the politicians are dependant on the “lobby”. Furthermore, as much it is easy, for a private company, to create a ghost company in the Carribeans to feed a couple of discreet bank acounts that will enable to have very “convincing” arguments, as much embezzling money in a state administration is not such an easy task !

There is thus no “nuclear lobby” with the meaning that we habitually give to this expression. But there is, in France, with no possible denial, a technostructure, composed of civil servants that have a strong “esprit de corps”. But such an “esprit de corps” also exists among the SNCF (the french national railways) employees or the physicians: should we suppress trains because we can’t bear the “esprit de corps” of the train employees and the strikes that derive from it ? Should we suppress health care to eradicate the “esprit de corps” of the physicians that are in charge ?

Then there are two “slightly different” activities in the nuclear sector :

- the military applications, that are effectively not very communicative, but they are paid for ! Plane or tanks manufacturers, or, before their banning, antipersonal mines producers, are not more eager to expose widely what they are doing,

- the civilian applications, that are not particularly “opaque”: EDF or Areva are subject to multiple obligations and rules, and must comply with a large set of standards regarding their emissions in air and water, that come on top the usual measures of financial control, so that the knowledge on what is going on there is in the norm, when not above. Here again, only the comparison is relevant: are we much better informed on what is going on inside the oil companies that, without exagerating much, have sometimes done and undone african governments or, as is the US, widely contributed to design the energy policy of the country ?

Are the regimes that cash in oil money (Saudi Arabia various Emirates, Iran, Irak, Russia, Lybia, Venezuela…) models of transparency and democracy ? Through driving our cars, we indirectly finance hand and head cutters, adultery women stoners, and the russian mafia: is it much better than paying the salaries of a couple of french employees that are, most of the time, perfectly honest civil servants ? In France, does the ministry in charge of energy really dictates his will to the first oil company of the country, whose name I have seen more often in the “judiciary chronicle” section of the papers than that of the CEA ?

As a conclusion…

The reader will have got my point : here as elsewhere, nothing is simple ! I do not say that nuclear energy is Alice in Wonderland, and most of all I don’t mean – and will never mean – that putting nuclear energy everywhere is the solution to all our energy problems. But only comparisons are of some interest, and, to produce significant amounts of energy, many “classical” alternatives (oil, coal, gas, large dams) or “renewable” alternatives (massive eolian, or biofuels, for example), have rather more inconvenients than nuclear power. In a world where we would accept to diminish significantly our energy consumption (I speak of us Occidentals, of course !), which seems quite indispensable to me if we want to avoid major problems one day, producing part of the residual energy with nuclear reactors seems perfectly acceptable.

Yet, once again, it is senseless to consider that we just have to call massively on nuclear power to “pull out of the fossil era”. Getting there requires to call (a lot) on energy savings (before everything else) AND on nuclear energy AND on renewables, mostly solar and biomass, without neglecting any possibilty: in front of a menace such as a “climate shock“, that could destabilize the whole biosphere, is it appropriate to refuse an element of the solution because it bears some inconvenients, when they are perfectly marginal compared to those it might help to avoid ? In short, up to where can we refuse to grade the risks ?

That one has been anti-nuclear in 1970, I can perfectly well understand, because it was pretty logical for who was worried by the planet’s future :

- atmospheric bomb tests were at their summit: nuclear technologies became first known to the public through military applications, what probably did not contribute – no big surprise ! – to give a good image of the “nuclear business”, but my present discussion bears only on civilian facilities,

- the technology for power plants was recent, hence we were too close to get a proper view on the effects on populations,

- and at last it was a time when the anxiety for the future of the planet came to a paroxysm (birth of the “political” ecology, for example with the candicacy of Dumont in France, fears of the Club of Rome with his famous report on the problems to come with perpetual growth, etc) and any technology allowing to do “more” and not “another way” was then easily subject to sharp critics. Incidentally, the fact that the fears of the Club of Rome have not yet materialized in a dramatic way do not allow to conclude that they will stay forever chimeric: of course, our civilization is mortal, and the good question is just to know whether our present behaviour significantly speeds up things towards its end or not.

But rejecting, in 2000, any form of nuclear energy to fight against much more upsetting menaces (climate change, geopolitical troubles of all kind in relation with fossil fuels supplies) than those linked to nuclear waste or the possibility of a major reactor accident, is closer to a sentimental choice than the proceeding of a “logical” reasoning. It is of course not illegitimate to make purely sentimental choices (I do some everyday: I have never tried to justify by “logical” arguments my love of blue color or of my kids), but it is then honest to say it clearly, which is rarely the case for the topic discussed here.