World famous track cyclist Robert Förstemann battles a 700w toaster!

For all individuals that work in the energy sector, kWh (or, for those twisted anglo-saxons, BTUs) are as familiar as litres of water to the gardener, or kg of flour to the baker. But actually, when thinking about it, no one knows what a kWh really is through his (or her) senses. One cannot “touch” energy; it is just some abstract figure on a piece of paper, sometimes the prerequisite to an invoice, and to grasp fully the meaning of figures related to energy, it will always be necessary – one cannot escape one’s senses – to associate to a given figure a “real” action or a “real thing” that will make it meaningfull to everyone.

It is therefore very difficult, with kWh, tonnes oil equivalent and other gigajoules, to make people understand how much our present energy consumption – that of each one of us, and not only that of the SUV driver or frequent flyer – has become totally “out of normality” compared to what the standard human condition has always been for ages.

In order to facilitate the understanding of this fact, I will do something that morals highly disapprove: bring back slavery. Indeed, men (and women!), like all machines, uses energy, that (s)he will afterwards transform – with a very poor efficiency, as we will see – into mechanical energy, and of course thermal energy. Men also transform the energy they use into information, what cannot be forgotten, but this is another story.

Men, how many kWh?

Actually, the energy unit that each one of us knows the best is not the kWh, but, most probably… the Calorie. Indeed, almost each one of us knows (and mostly women a couple of months before the summer while reading their favourite magazine!) that a sedentery person – that is with little physicial activity – consumes about 2000 Calories per day, through eating. These Calories represent nothing else than the extractible energy content of what we eat, and our body will of course make the best use of it, except when some diet seller persuades us of the opposite.

Since we are discussing energy here, it is then possible to convert our 2000 daily Calories in kWh, which is another energy unit, that can therefore be used with any form of energy, including food. As 1 Calorie (with a capital C) = 1000 calories (with a small c) = 4,18 thousand joules, and as 1 kWh = 3,6 million joule (if this is too hard just trust me), we can conclude that a man (or woman, sorry again!) with no significant physical activity absorbs about 2,3 kWh per day.

In other words, the basic metabolism of a human body uses 0,1 kWh per hour, and is used to maintain our body at 37 degrees Celsius. When we are still, all we eat will be used to radiate heat just as a 100 Watts light bulb (so that’s all the use of cooking delicate meals: all will end in heat just as in a vulgar light bulb!). This is why rooms heat up when they are crowded: with 100 Watts per stockholder, any general assembly becomes hot in the true sense of the word before any other meaning applies to the same adjective!

Let’s now come back to our slaves (fictive, of course), to see how many we should each have at our service to get the same level of comfort we have with machines and “modern” energy. Everybody, unfortunately, will not have the luck to have Schwarzenegger or Stallone at his service, with bodies that can jump to 1 kW of power when in full effort, and one will probably have to do with “ordinary” slaves, such as me, whose body probably doesn’t go over 200 watts of output when I sweat like hell.

Suppose I have a (fictive) slave that works very hard 10 hours per day, and while doing so needs 5 times the “basic energy” of someone standing still. It means that my slave will use on average 500 watts of food per hour, that is 5 kWh for 10 hours. Then, for the remaining 14 hours in the day, as (s)he will rest because I am a good master, (s)he will use 100 watts as mentionned above, with a total of 1,4 kWh (that is 100 watts x 14 hours). After a day of very hard work, my slave will have used 6,4 kWh (or 5000 Calorie).

If slave is a woman, using only 400 watts in full effort, and authorized to work only 8 hours per day (except if equal conditions are a must here also!), the energy consumption for the whole day will be limited to 4,8 kWh, and if we consider labour which is not physically intesive (washing, cooking, or whatever), requiring only 250 watts of food per hour to be performed, but done 12 hours per day, we will need 4,2 kWh over 24 hours to feed the organism. In first approximation, a body working hard will use about 5 kWh of food per day.

This is where we start to understand that our species has performed a fantastic “power breakthrough” when domesticating fossil fuels: with 1 euro (which is about 1 dollar, Wall Street specialist will excuse me to concentrate on magnitudes), I can buy almost 1 litre of petrol (or gas), that contains about 10 kWh of thermal energy, which is about the equivalent of the intake of two “slaves” working for a full day. And oil would be expensive?

But the price of energy will seem even more ridiculous if we take into account the efficiency of the human machine, equally ridiculous. Let’s picture a worker that digs a big hole, and shovels earth all day long to do so. If our man (it’s seldom a woman, as a matter of fact) throws up one shovel or earth every 5 seconds during 8 hours of work, he will have carried 17 tonnes when the working day ends. If the hole is 1 metre deep, a magnificent formula that all those that did not sleep to much in physics certainly remember (E = mgh) allows to conclude that the mechanical energy used to do so is worth… a little less than 180.000 joules, that is an utmost ridiculous 0,05 kWh! If our man has absorbed 5 kWh during the day to stand this continuous effort (just try to do it one day and you will understand), we see that the mechanical efficiency of the human machine is something around 1%. Abracadabrantesque!

The efficiency of legs, however, is better than that of arms: if the same worker, weighting 70 kg “all naked”, has climbed 2000 metres in the mountains, with 30 kg on his back, he will have produced (70+30)x2000x9,81 = 2 megajoules of mechanical work, that is roughly 0,5 kWh. As he will probably have eaten about the same amount, the efficiency makes an astronomical leap in this case, becoming almost 10%.

In the same time, an internal combustion engine has an efficency ranging in 20%-40%, which means that the mechanical energy produced by the engine represents about 20% to 40% of the thermal energy enclosed in the fuel. 1 litre of gasoline, poured into such an engine, will therefore produce 2 to 4 kWh of mechanical energy. If my sole purpose of having slaves is for the mechanical work they produce, then we see that with one litre of gasoline, and its 2 to 4 kWh of mechanical energy after going through an engine, we get the equivalent of 100 (large) pair of arms (at 0,05 kWh each) during 24 hours, or 10 pairs of legs (at 0,5 kWh each) over the same period of time. And oil would be expensive (bis)?

It is obvious, when seeing this astronomical price difference between human energy and fossil energy that, if the price of energy remains constant, anything a machine can do will eventually be done by a machine if micro-economic logics apply everywhere and before any other consideration. Fortunately it is not always the case, and fortunately also it is not frequent that a worker produces only mechanical energy, without the slightest bit of intelligence (which is worth much more) or ability to manage something not expected (which is considerably more expensive – if possible at all – when done by a machine).

How many slaves in our modern life?

Now that we know that a working human being uses about 4 to 5 kWh per day, and restitutes 0,05 to 0,5 kWh of mechanical energy over the same period of time, we can convert almost any energy consumption of the present daily life in “slave equivalent”, which is like saying that through our energy consumption for this or that we have so many fictive slaves at our service. You don’t fear to feel dizzy? Then here goes…

In 2011, A French – very representative of an European or Japanese, and for bid bag Americans, Canadians or Australians just multiply by 2 – consumes about 30 000 kWh per year of final energy (50 000 kWh per year of primary energy) without taking the imports into account (because imported goods and services “include” the energy used elsewhere to manufacture them).

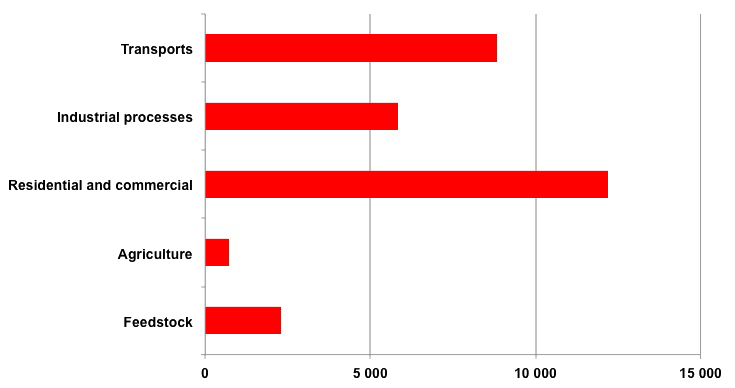

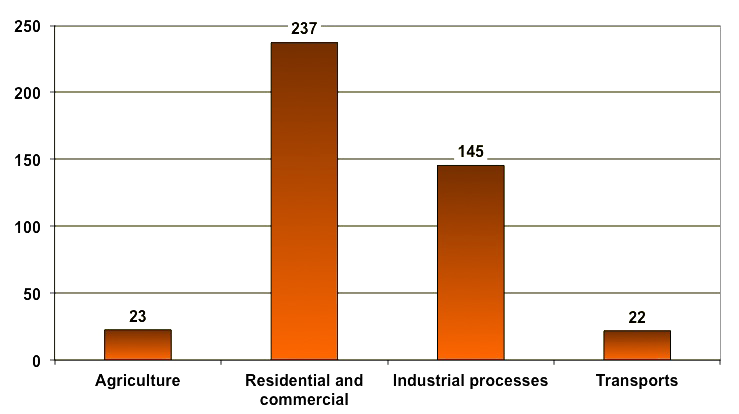

Final energy consumption per usage and per French, in kWh, in 2011.

The total represents about 30.000 kWh. For “Industry”, only the energy used in processes is accounted for (not heating of premises, which is accounted for in “heating”). “Feedstock” corresponds to the oil, gas and coal that are used as raw materials to manufacture plastics, chemical products, soap, etc

Source : Commissariat Général au Développement Durable, 2012

We will now play at the “slave master game” (as gentlemen, still) by converting all these energy consumptions into “slave equivalents”. We will use the following rules:

- when energy is used to obtain heat, the equivalence will be one man = 2,5 kWh per day (what is used is the basic metabolism), or 876 kWh per year,

- when energy is used to obtain a mechanical effect, it depends:

- if the desired effect is just “raw power” (lifting a stone on a construction site, for example), we will use the “leg equivalent”‘, that 0,5 kWh per working day, and assume that hard works happens 2/3 of the year (our slave must rest not to die too fast!), for a yearly total of 128 kWh (of mechanical energy per “slave”),

- if the desired effect requires precise movements (picking up an orange on a tree, or assembling two parts of a chair, for example), we will use the “arm equivalent”‘, set at 0,02 kWh per working day (precise movements are less powerful than when shoveling earth), and assume that hard works happens 90% of the year (our slave also rests, but less), for a yearly total of 6,5 kWh (of mechanical energy per “slave”),

- We will now specify the simple allocations that we will perform depending on the type of energy use:

- in France, agriculture mostly uses oil, and a little electricity (very similar in other OECD countries).

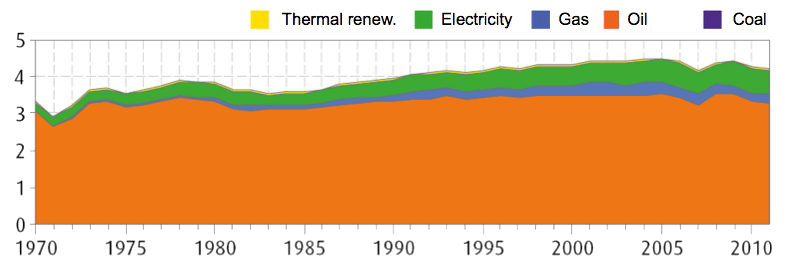

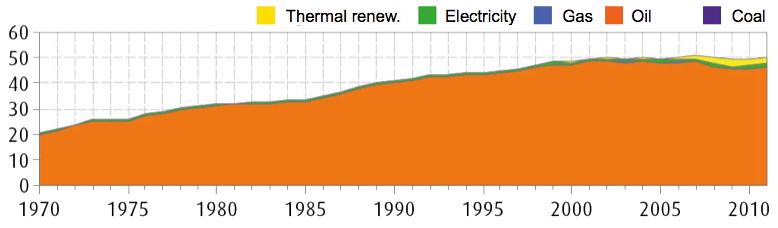

Energy consumption in French agriculture since 1970, in million tonnes oil equivalent.

(one tonne oil equivalent = 11600 kWh).

Source : Commissariat Général au Développement Durable, 2012

We will assume that oil is used into internal combustion engines (on tractors, combine harvesters, etc) with a 20% yield, and is used mostly for “precision work” (planting, plant care, harvesting of grain and vegetables, etc). Electricity is supposed to be used for “precision work” also (milking, sorting, etc) and marginaly for lighting and heating. TO reflect this set of assumptions we will suppose that 70% of the total is lost as heat (in engines), and in the remaining 30% we have 20% that are “mechanical arms” and 10% “mechanical legs”.

-

- Industry uses a little of everything.

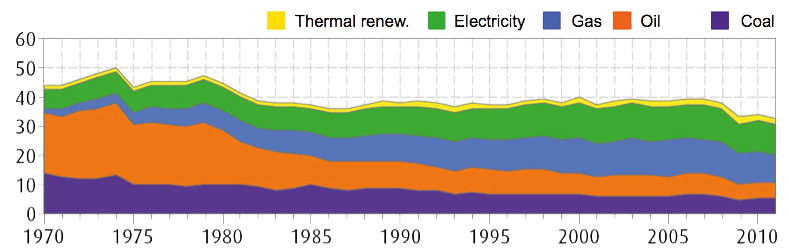

Energy consumption in French industry since 1970, in million tonnes oil equivalent.

(one tonne oil equivalent = 11600 kWh).

Source : Commissariat Général au Développement Durable, 2012

Gas and coal are supposed to feed boilers (only heat), and oil is supposed to feed engines with a 20% yield. Electricity has mostly a mechanical use (conveyors, mechanical machines, pumps, etc). At the end we have 50% of the total which is useful heat, 80% of 15% which is lost heat (in engines), and for the mechanical fraction (roughly 35%), we will assume that 2/3 are “raw power” (or leg equivalent) and 1/3 precision work (thus arm equivalent).

-

- Residential and commercial (“commercial”, here, is everything which is neither industrial nor agricultural: schools, homes, hospitals, prisons, malls, offices, etc) use also a little of everything, electricity coming first in France

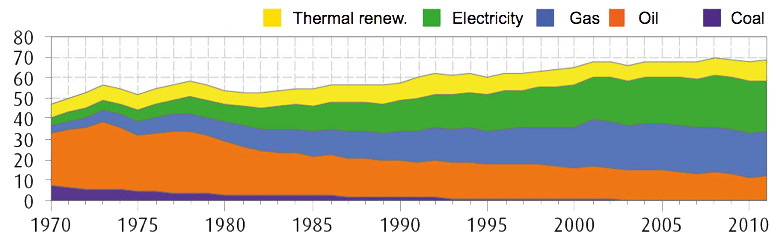

Energy consumption in French residential and commercial since 1970, in million tonnes oil equivalent.

(one tonne oil equivalent = 11600 kWh).

Source : Commissariat Général au Développement Durable, 2012

We will assume that gas, oil and thermal renewable only give useful heat (heating, hot water), and that 2/3 of electricity actually also give useful heat (heating and hot water, but also cooking, the heat supply of lighting, heating of the water in washing machines and dish washers, air con, atc). For the remaining 1/3 of electricity, we will assume that 3/4 correspond to “arm equivalent” (because printing paper, washing a dish, removing dust or transmitting information is far from being only raw power), and 1/4 only to “leg equivalent” (lifts, for example).

-

- And at last transportation uses only oil, or almost!

Energy consumption in French transport since 1970, in million tonnes oil equivalent

(one tonne oil equivalent = 11600 kWh).

Source: Commissariat Général au Développement Durable, 2012

Here we have an easy go: all goes into engines, with 80% giving lost heat, and 20% converted with “leg equivalent”.

-

- Well, with this simple set of assumptions, here we are, with… the equivalent of more than 400 slaves per French!

“Slave equivalent” (still fictive!) that correspond to the French energy consumption in 2011, with the above described assumptions.

Most Europeans are in the same rang, and thus have the equivalent of 400 to 500 slaves 24 hours a day! (without the imports, that represent an additional 100 in France).

Another way to give the same conclusion would be to say that not only energy is not expensive, but it is worth nothing. The abundance of cheap energy has turned the most pitiful inhabitant of an industrialized country into a mogul, living tremendously above what the standards were a century or two ago. Who could, before coal, oil and gas (and marginally the rest) invaded our lives, afford 500 servants with his sole income? The king or a large country, and that was it!

If we look at the results in detail, here are a couple of additional comments:

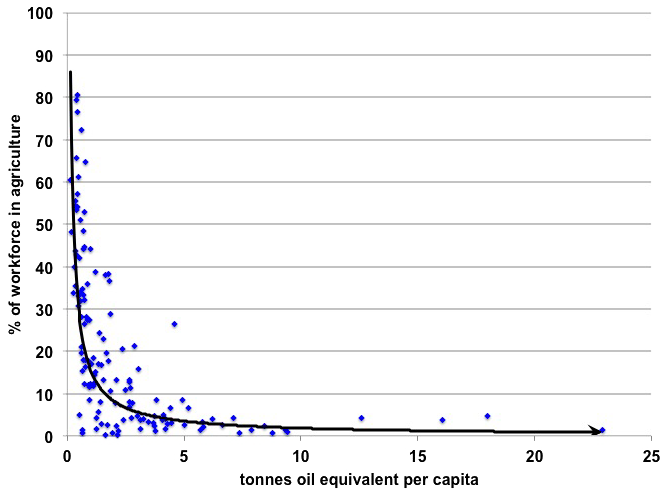

- To have the French eat as they eat without the energy supply of agriculture, France should have… 1,8 billion peasants (feeding 60 millions inhabitants). Well, it’s possible that with a different set of hypotheses we go down to 500 million, but still we measure here the fact that the first role of energy is to free workers from the fields, allowing them to do all the other jobs that we presently have. And besides this energy is mostly invested into meat at all meals (because cattle and animal farming is the main cause of grain production), that would not be possible without abundant energy. We definitely eat oil and gas!.

Share of active population in agriculture (vertical axis, %) as a function of energy consumption per capita (horizontal axis, %) in every country with available datas.

The black curve shows the general tendancy.

Source: World Bank, 2013.

- For industrial processes, the result is coherent with what can be observed everytime a process goes from men to machines. For example, a miner with a shovel and an axe will extract 100 times less ore or coal per day than a miner that actually drives a bulldozer, a bumper, or an excavator. A crane operator will lift – through his crane of course – 100 times more weight in a day that if he had to carry everything on his back, etc. We all have 150 (or more) workers at our service – in the form of machines in factories – that manufacture our clothes, glasses, plates, tables, cars, windows, televisions, and even our barbecues and beach towels…

- For transportation, the result can seem – comparatively – low, but we should not forget that transportation means are used a little number of hours in a year: about 200 hours for a car, when I assumed that my “energy slaves” work all the time. The most modest car, with its engine power of 40 kW (70 horse-power or HP), pulls as hard as 90 world champions on a bicycle (and as hard as 500 people like me!). If my “energy slaves” were called upon only when I took a car, then I should have 200 slaves rather than 20. Another figure is enlighting: a horse-power (0,7 kW) does indeed represent the power of an average horse. It means that the minimum salary worker, today, can have the equivalent of a 60 horse coach for 6 to 8 months of salary. And energy would be expensive? Even a small moped provides 2 to 3 kW of engine power, that is the equivalent of 15 to 20 human being pushing hard on pedals…

- And at last, for residential and commercial, we have an idea of the tremendous number of machines hidden everywhere in buildings and that “serve” us, be it domestic appliances, computers, lights, lifts, pumps, hospital equipment, fridges in shops, or bells in schools…

This simple calculation suggests some less pleasant conclusion: it is not only the “way of life” of an American star or a business mogul which has become “not sustainable”, but that of each and every Western man, starting at the bottom of the social ladder. The effort to become “sustainable” (in the way that it can be sustained for a couple centuries) is not only an issue for those who are well-off: with more than 7 billion men on Earth, the “modest” of all Western countries (including a part of China, now) will also have to do something, because even them are contributing to an overshoot of the physical limits of the planet.

The good news is that a division by 4 of the fossil energy consumed by each French, which is what it takes to mitigate climate change, still means, with the present technologies, close to a hundred of “slave equivalent” per individual. It remains far from the Stone Age!