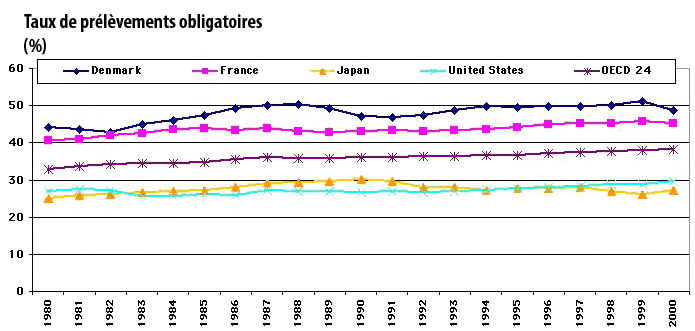

Taxes in general, whatever their purpose is, easily raise animated discussions when they are evoked in the French press, and, for what I have been able to read, it seems that the situation is pretty the same in a number of our neighboring countries in Europe. In the “energy and environment” category, taxes on energy rank in a very good place, along with nuclear power, for hot debates. What are the most common arguments put forward by those that consider that we pay too much taxes on energy ?

- we already pay enough taxes in general (or even “tax wedges are excessive in our country”),

- if we raise the taxes, the burden first goes on “modest” households, wich is not fair,

- “people” need their cars, and nothing should be done to prevent them using it,

- taxes will hinder the competitivity of the economy, so we should not raise them, and instead lower them,

- the government “just has” to develop renewable energies, biofuels, etc, so that we be able to go on driving just like today, with no price increase, and without bothering the taxpayer.

I will not swear that I have not forgotten a thousand and one other arguments that opponents of taxes on gasoline appreciate, but for a start we will stick to what is above ! And where I will try to get, as surprising as it might seem to the reader, is that progressively rising taxes on fossil fuels is something we had better do if we want not only to preserve the environment, but also “modest” persons. In order to go step by step, I will proceed by successive questions. Those questions are probably the same in any country, whatever the tax wedge is !

Don’t we pay too much taxes already?

The first element that perverts the discussion on taxes in general, and on the income tax in particular, is that any tax is perceived as a confiscation, when it is only a redistribution, that we all benefit from through services. Why is this confiscation feeling so widespread ? It’s actually very simple, and bound to the very human nature : we can all calculate to the cent how much we pay in taxes, when no-one knows how to calculate to the cent how much the state – or any other entity that raises taxes – redistributes as teachers, police officers, roads, combat planes, meat paid cheaper (through subsidies to agriculture), or museum maintenance.

There are several exceptions, when the state directely allocates a subsidy (to a company, a charity, or an individual), but that represents a marginal part of the state’s spendings, the main part being devoted to services for which we do not have a direct monetary equivalent though we all benefit from them. As we all have a certain tendancy to consider that what cannot be evaluated to the cent is worth nothing, we get the impression that we have given without having received anything, which is of course not true.

The question of whether we should pay less or more taxes can then be put another way : what is, in the end, the share of the services we use for which we wish that they are handled by state administrations ? Because, of course, if we want to pay less taxes, the state will have less means to provide us with servies : do we accept, as a couterpart, less teachers, seargents, and highways ? Of course, anyone will say : the state “just has” to be more efficient, because everybody knows that civil servants are a joyous lazy bunch, spending their time in holidays with the taxpayer’s money.

If it if definitely possible to find deeply lazy individuals in the state administration, it is also possible to find some in perfectly private companies ! And if we examine things factually, statistics do not show that employees of private companies are more productive than those of public administrations, so that more or less taxes is much more a polotical choice than an economic one.

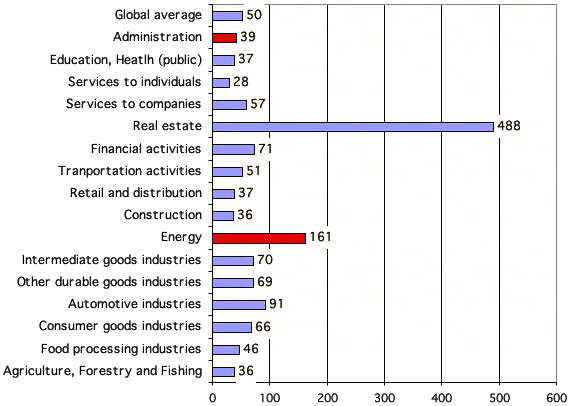

Added value per employee depending on the nature of activity in 2003 in France.

It is easy to see that no conclusion can be drawn from the fact that someone is a civil servant : the energy sector, where 85% of the employees are civil servants (in France), has a productivity per employee that tops that of any other industrial sector, and the administration is more productive (because the added value per employee is nothing else that his contribution to the GNP) than retail and distribution activities !

Source : INSEE/comptes de la Nation, 2004

And then, for a number of activities, the very idea of efficiency is hard to characterize : what is the efficiency of the army ? (that ranks 3rd in the French federal budget) The number of ennemies killed by soldier, even in peace times ? And how does one increase the efficiency of a teacher ? (education is the first source of exepenses of the federal budget) By increasing the number of pupils per class ? What do the taxpayers, who are also parents, think of the idea ? Should we ask professors to teach at the same time French, english and Technology to increase the number of working hours ? By suppressing part of the holidays, so that they work longuer ? There are always progresses to be made everywhere, but one realizes that a soon as we try to get over the slogan things are far from being obvious. To answer a slogan by another, is things were so obvious, it would have been a long time since they were done.

In short, we pay as much taxes as we want services from the federal administration. We may very well pay less taxes, but the state will provide less services, and the private sector generally performs no better to grant equivalent services, as we will see a little lower.

Shouldn’t we pay already more taxes ? (in France, and in most european countries)

We might even go further, and say that, in fact, we should already pay more taxes ! Indeed, the balance between revenues and expenses, at the federal level, is far from being reached, and is even each year further from being reached. In other words, we already live above our means (this is true in France as in most european countries with a persisting deficit), and actually more and more above our means with time. Few of my fellow citizens know that the French federal budget spends each year 20% more than it earns, which means that when the federal budget spends 100, it gets only 80 in taxes, the rest being financed through an increase of the debt, and this latter uses a growing share of the revenues for the sole payement of the interests.

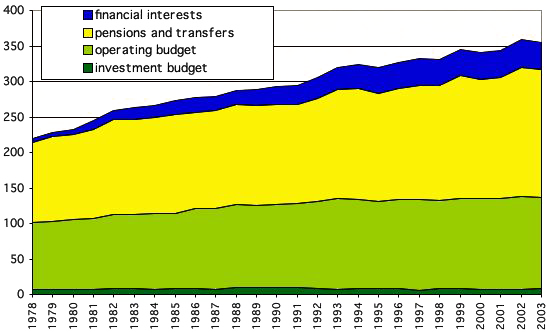

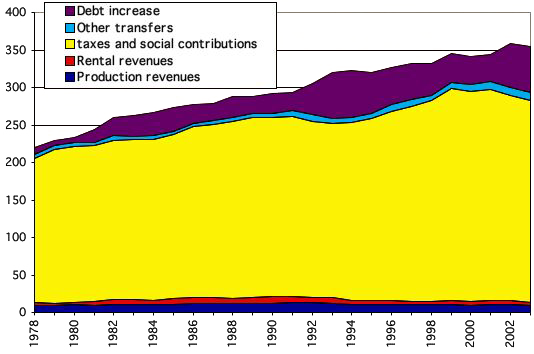

Evolution, in constant euros (of 2003), of the main components of the federal budget.

Pensions and transfers gather pensions and revenues collected on the behalf of other administrations (social security, cities, etc) .

The sole payement of the interests of the long term debt (that increases each year, see graph on the right) is now equivalent to 30% of the operating budget.

Source : INSEE/comptes de la Nation, 2004

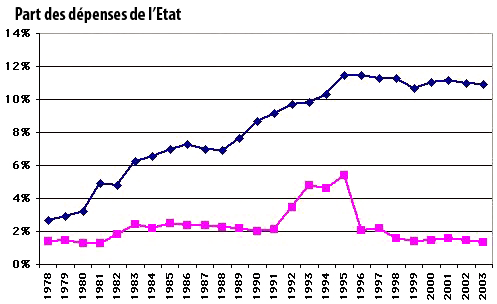

Percentage of the federal budget’s spendings absorbed by the payement of the interests of the long term debt (blue), and, as a comparison basis, same for social security (pink).

Another trend initiated during the last decades which is not sustainable !

Source : INSEE/comptes de la Nation, 2004

The sole payement of the interests of the long term debt (without even mentionning to reimburse part of it) has become the second spending item of the federal budget, with more than 10% of the total, and the debt increase has represented 20% of the revenues of the budget in 2002 (see pie below). The usual presentation of the deficit – which mainly concerns the federal budget, the social security and the local administration budgets being almost balanced – as a share of the GNP is misleading : the federal budget does not own the GNP, but just the taxes it cashes in ! In this context, and knowing – but we will discuss this point more below – that increasing the productivity for public services is not easier than it is for private companies, any suggestion to lower a tax A without raising a tax B is equivalent to wishing at the same time :

- either a diminution of the public services,

- or a debt increase, that is living a little more at our kids’ expenses (because normally, all that is borrowed should eventually be given back !). It seems pretty obvious that so far it is the way we have chosen…

Evolution, en euros constants (de 2003), des diverses ressources de l’Etat depuis 1978.

Le total de l’année correspond bien sûr aux dépenses. On note une tendance de fond à augmenter chaque année un peu plus l’appel à la dette (aire violette du haut).

Source : INSEE/comptes de la Nation, 2004

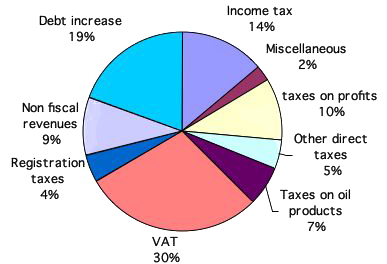

Breakdown by origin of the federal budget’s revenues in 2002.

The debt increase was, that year, ranking second for financing the budget, with almost 20% of the total. IT was not an exceptional year.

Source: Loi de finances 2002

In short, knowing that we already use more than our tax money, is lowering taxes the best thing to do ? And to come back to the ultimate object of this page, that is taxes on energy, if we wish to lower the french tax on oil products (TIPP), that represents 7% of the revenues of the federal budget, what are the other taxes we should increase, or what are the services we should do without?

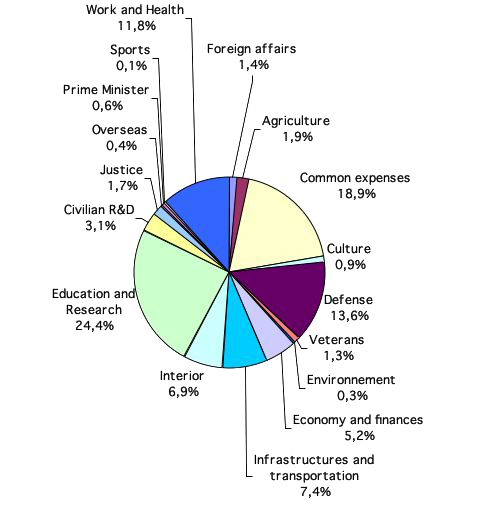

Breakdown by ministry of the federal spendings in 2002.

If we lower the TIPP, and knowing that “there just is to increase the efficiency of public money” is an appealing slogan but not a practical solution (any partisan just has to ask oneself himself whether it is that easy to increase the efficiency for his own work !), what do we do : more of another tax, less services (which ones ? choose in the above pie !), federal bankrupcy, or a debt increase ?

Source: Loi de Finances 2002

But don’t our neighbors get more by paying less?

The common illusion that public services could be more effective with no more tax money is comforted by one of the favourite exercises of the press when taxes come around, which is to compare the level of tax wedge in our country and in other European countries, to point out – which is perfectly true – that we French are in the high end of the bracket. I am ready to bet significant sums of money that in other occidental democraties the papers offer similar points of view.

But once we have made this observation, everything is not said ! Indeed, the public services do not handle the same services in the various states. Rather than comparing mere percentages, that just reflect the fact that a more or less large proportion of the basic services are taken care of by the state, but not necessarily in a worse way, it will be more relevant to see how much money is necessary to get the same kind – and level – of service in various countries, to see if the said service is granted for a lower cost when it is managed by a private business, what would support the idea that private money is more efficient than public one.

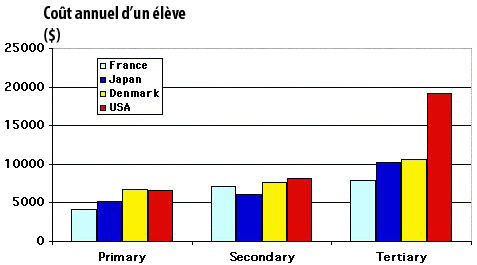

Let’s take education as our fist example. How does the cost of educating a child in France compare with that of other countries that have a lower ratio of public money in the educational system ?

CoûtAverage anual cost of a scholar in dollars, depending on the level (primary, secondary, tertiary).

Source : OCDE.

The above graph is clear : the average anual cost of a scholar is significantly higher in the US than in France, the ratio of public money in the educational system being higher in the latter. So we have at least one example to show that a more “liberal” system (since everyone is supposedly free to pay whom he wants in the US, and not mandatory taxes to a despisable state with lazy employees) is in no way a more efficient one ! And a comparison is relevant here, since the service granted is equivalent in France and in the US : the name of the game is to learn to read, write and calculate, and the efficiency of basic education, measured with tests taken by the adult population in reading or elementary mathematics, is about the same in France and in the US (OECD data).

So in the US the choice has been made to have an educationnal system only partially funded by public money, but if we look at the total paid by the inhabitants for education, summing up taxes and direct contributions to schools or universities, the US system is costlier than the French for about the same service. A “wise consumer” looking at figures in this precise case will conclude that he had better give his money to the federal buget – through taxes – for basic education financing, rather than paying less taxes but paying more in total if the system is partially private.

If we look at things a little closer, there is something even more subversive for “liberals” : the higher the tax wedge, and, on average, the higher the proficiency in the mother tongue !

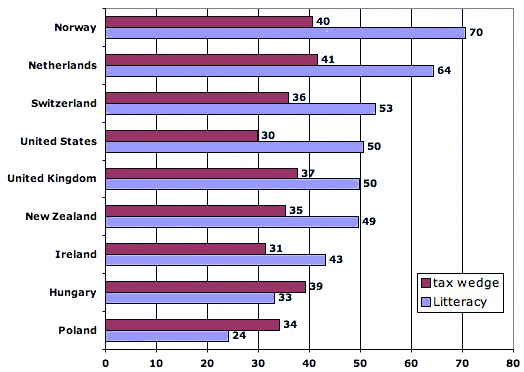

Tax wedges (in % of the GNP), in various OECD countries, and litteracy in the mother tongue for these same countries, measured using an OECD indicator.

On average, the higher the tax wedge, and the higher the litteracy of the population. Doesn’t it incline to consider that the education systems mostly financed by public money are the most efficient ?

Source : OCDE, 2004.

Another example : retirement pensions. In the US, the income of someone aged over 65 is, on average, 16% lower than that of someone aged 18 to 64 years. In France, the difference is 15% : almost the same. But in the US the share of public money in the pensions amounts to only half of what it is in France.

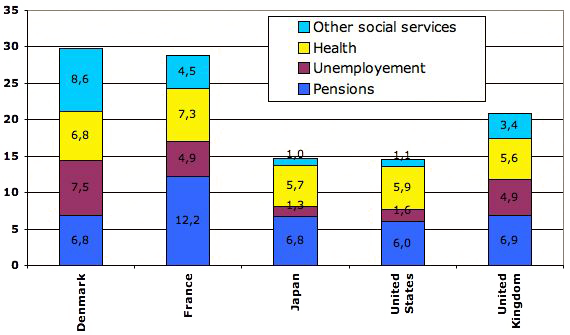

Percentage of the GDP devoted to social (and public) spending for several OECD countries.

Source : OCDE, 2004.

As retired people keep comparable incomes on both sides of the Atlantic, but the State pays twice less in the US, the logical conclusion is that the other half is payed by other means (through savings given to pension funds during the previous part of one’s life, for example). Americans pay less money to mandatory retirement regimes, and then get less money out of them when they retire. There is no miracle, with retirement pensions remaining the same in every country in the world while some people are paying much less money during the active life than others ! The question is just that of the entity handling the pensions, but the efficiency is no better when the entity handling the pensions is handled by the state.

It was not the main idea of this page, but we can also investigate other sectors, such as health, to show that it is not enough to just look at how much taxes we pay to get to relevant conclusions : we must above all examine how much money is spent overall for an equivalent level of service, if part of the services managed by public institutions are managed by private businesses. And the conclusion is often the same : in countries where taxes are lower, households spend the same or more (because shareholders claim their part !), topping state money with with direct spendings, to get the same thing at the end.

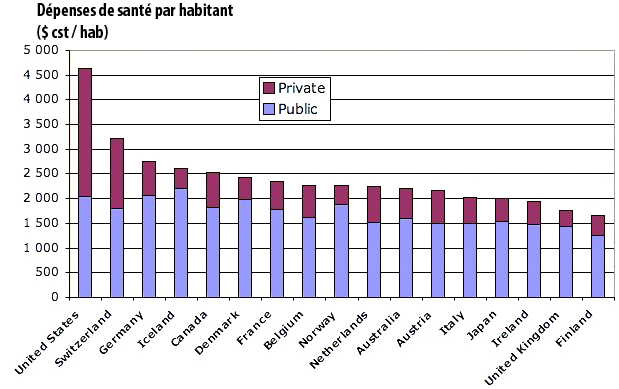

Yearly spending per capita for health in various OECD countries, in 2002 US $, with a distinction between what comes from public money (public) and what comes directly from households or private health insurances (private).

Countries with a very high ratio of public money in the health system (hence a higher tax wedge) actually offer lower overall health costs to their inhabitants.

The US example is particularly enlightning : it has the lowest ratio of public money in the health system of all OECD countries, but the health of its citizens costs a share of the GNP which is twice what it is in European countries, except Switzerland ! Talk about the efficiency of private businesses that requires to double the share of the GNP devoted to health..

Source : OCDE, 2004.

We might even go further in our “subversive” thoughts : paying more taxes rather mean a longuer life expectancy that paying little !

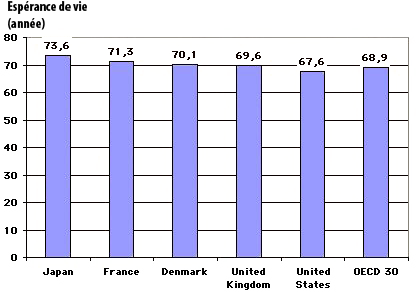

Life expectancy in various OECD countries in 2002.

American citizens pay less taxes that French, but live 4 years less on average. A lower tax wedge is therefore not necessarily the guarantee of a better world !

To be honest, a lower tax wedge can also happen along with a high life expectancy, as in Japan (that has, still, a much higher ratio of public money in the health system than the US).

Source : OCDE, 2004.

So indeed, citizensof various countries in the world do not pay the same amount of taxes, but the state does not grant equivalent services everywhere (otherwise it is obvious that we should lower taxes !). Just comparing tax wedges, and letting people believe that we could pay less and still get the same quality of service is alas ignoring the facts, or holding an irresponsible political speech : if it might be the case for some marginal cases, nothing, in the available figures, allows to support such an idea for the whole of the public spending.

If we want less taxes, we must accept the unavoidable consequence : less public services, with a compensation through private money, that will be no more efficient, and most of the time even less efficient, than public one.

But our neighbors that pay less taxes are globally richer!

There remains to discuss one of the arguments often presented as a “no reply” one : if we pay less taxes, we work harder and get globally richer, and thus it is not a problem if some services are costlier : overall, we are better off. Of course, such a position is equivalent to considering that “better” is only “richer”, and that all we have just exposed is negligible : it would be necessarily preferable to have more money but a lower life expectancy, or a lower level of education, or a higher proportion of overweight people (weight in excess might be a very unpleasant thing for daily life, and lots of people would probably accept to earn significantly less to get rid of it !).

Such an argument also ignores the fact that our economic system is not taking into acccount future negative effects that derive from our activity, such as climate change, but, most of all, it happens to be false even when sticking to the monetary unit.

Indeed, if such a reasining was true, one should observe a decreasing tax wedge, on average, when wealth – measured with the “classical” unit of GNP per capita – increases. Tough luck : it’s exactely the opposite that happens ! This confirms, once more, that “liberal” positions on taxes are much more often based on ideology than supported by objective facts.

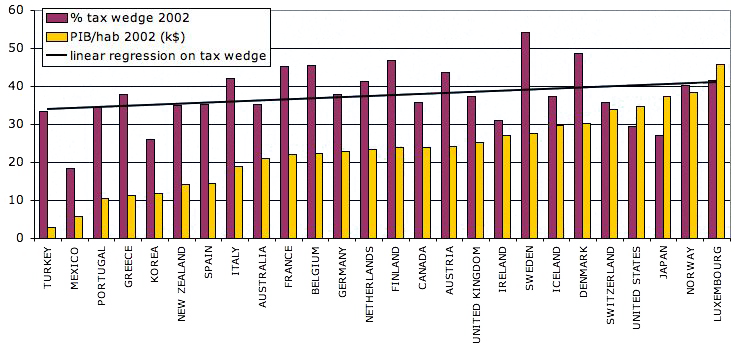

GNP per capita in 2002 (in thousands US $) in 26 OECD countries, ranked from the lowest to the highest (left to right), and tax wedge for the same countries.

A linear regression on tax wedges is explicit : the tendancy is more to higher tax wedges when the GNP per capita increases, and not to lower ones !

Source : OCDE

And what about energy, now?

After this “long trip” in the tax world in general, to show that facts do not support that raising taxes is a fool’s idea and that’s it, it is now about time that we discuss taxes on energy in particular. Just as it has seemed relevant to begin by recalling a number of raw facts for taxes, it will be relevant to do the same for energy, since we willingly forget most of them when we discuss the subject (this is valid for France, but even more for other countries with less nuclear or hydro electricity) :

- 75% of our final energy consumption in France is “fossil” energy (oil, gas, coal). We remain much closer from “all fossil” than we are to “all nuclear” (but nuclear power is not without interest!).

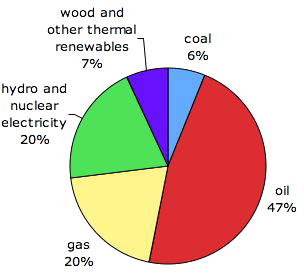

Breakdown by nature of the French final energy consumption in 2002.

Let’s recall that France produce less than 1% of its oil, about 3% of its natural gas, and no coal any more : 75% of our final energy supply hence come from abroad.

Source : SOeS.

- oil, gas and coal are subject to depletion. Thus, not only the consumption cannot grow indefinitely, but it cannot even remain indefinitely constant (sorry, that’s maths !). It means that if the oil demand (or gas, or coal) in the world remains at least constant “forever”, the supply is bound to become progressively insufficient, and thus prices will increase (and increase enough so that the demand doesn’t remain constant, but fits the lowering production at most). The only way to avoid that a declining supply curbs the demand through tensions on prices is to curb the demand voluntarily faster than the limits of the physical world would do it for us. The only point that can be debated (but it is not a minor one, indeed !) is to know whether the unwanted decrease of the production will happen in 10 years or in 250. As for oil, technical papers suggest rather 15 years than 250, and for fossil fuels as a whole it seems that “something” will happen before the end of the 21st century.

- The story of the last decades tells that the main driver of the global energy consumption is not the efficiency of the device that use some, but energy prices, or more exactely the portion of our income that it is necessary to devote to energy spendings (or in other words still the main driver is the time that it is necessary to work to buy a gallon of gas or a kWh of electricity). When devices that use energy become more efficient, if in the same time energy prices get lower, expressed as a fraction of the purchasing power, a same object costs less and less to operate. The result is an increase in usage that goes faster than the efficiency gain ; it can be witnessed everywhere in the world in general, and in France in particular with cars (we have now 30 million road vehicles when we had only half that amount in 1974), heated surfaces (that doubled during the last 30 years), or domestic appliances (electricity consumed by domestic and office appliances has been multiplied fourfold between 1974 and today, though each fridge taken individually consumes less).

- History has taught us that energy price increases sometimes happen in a brutal way, as “shocks”, which is pretty logical when a large share of the transactions are done through financial markets, which are volatile by nature. There is no element, today, that would allow to conclude that the price increases that would result from declining oil production will be progressive, without any more or less violent hiccup from time to time. Actually, it’s even the opposite that seems highly likely : as long as we remain heavily dependant on oil, and that a significant share of the supply is done through short-term contracts, a future oil shock seems unavoidable ; it’s just a matter of time. And as long as the gas consumption is rising, future gas shocks are equally unavoidable, for exactely the same reasons.

A logical conclusion of all that has been exposed above is that the more we try to keep low prices for fossil fuels in the short term, the more the consumption rises in the short term, and the more a regulation through shortage – that will translate into one or several shock(s), with potentially unpleasant consequences such as unemployement – is likely and close.

The price of fossil fuels is therefore bound to increase in the long run, except if a major regulation (fall of an asteroïd, massive outbreak, or any other event suppressing a large part of the population and/or the consumption per person) happens first, without even allowing, as a matter of fact, to get rid of climate change later on. From there, the alternative to an increase of taxes on fossil fuels is not evercheap oil (or gas, or coal), but just the choice of letting oil (or gas, and later coal) prices rise as a result of tensions on markets, probably with sharp increases from time to time, and the choice of letting the price of climate change increase in the long run, here also with a much higher probability that it gets felt through brutal evolutions than smoothly. Clearly, refusing a progressive increase of taxes today is equivalent to paying damages happening in a much less progressive, and that will cost much more, “later” ; “later” might well be in less than a decade.

If we summarize all this with a question, do we prefer to see the price of domestic fuel oil, gasoline, diesel oil, jet fuel, natural gas and coal rise a little every year, or should we seek to let prices low “as long as possible”, and quietly wait for future oil shocks or climate shocks to do the job for us, more brutally, and most probably (much) before the end of the century on the basis of available data?

Are fishermen, truckers, farmers, and other gasoline-intensive jobs cursed by fate?

It is perfectly legitimate, when one spends one’s whole day driving a tractor under the rain, or working on the deck of a fishing boat in december (in the Northern Hemisphere !), for a salary generally lower to that of someone comfortably sitting in a heated office, to consider that the government “must do something” to help these jobs, that use a lot of fuels, when the prices increase.But knowing that these fuels will become more and more expensive in the course of a generation or two, and thus that it will be necessary to adapt whatsoever, should we help these professions otherwise than through lowering taxes on fuels, which is clearly choosing aenesthesy without cure, allowing these professions to temporarily forget that fossil fuels will be costlier one day anyway ?

Rather than lowering the price of fuels they use, which does not encourage them to anticipate an undavoidable evolution because of oil and gas (and coal, later) depletion or mitigation of climate change through a carbon tax, and thus progressively modify their actitivies to rely less on fossil fuels (which, let’s not dream, will lead to a lower production and higher prices, but it’s the kind of little inconvenient we should accept if we do not want major trouble otherwise), we’d rather oblige the clients (that is you and me !) to accept price increases that come from fuel prices increases. Why not index the prices of agricultural products, fish, or road transport on fuel prices, just as rents are indexed on the construction costs (in France), making it a legal obligation to include energy prices increases in the selling price ?

If production costs increase, isn’t it normal that the end-user consumer pays for it, since (s)he is the final beneficiary of production ? Professions that heavily rely on fossil fuels could thus include, in an homogeneous way, all energy price increases, without distorting the competition, since everybody would raise the prices the same way, and it’s the market that will regulate the global consumption, what will definitely have an impact on the production, but a more progressive one, letting more time to adapt. Of course, this requires to modify a little the standard demagogic position, which asserts that cheaper prices and consumption increases are evolutions that would be granted for eternity, when the laws of physics are aginst it. All it does it just leading to the common belief that the world is infinite, what clearly makes the energy and climate change problems harder to solve.

Shouldn’t we give subsidies to renewable energies rather than increasing taxes on fossil fuels?

The production price of fossil fuels, today, is considerably lower than that of renewable energies. Let’s take the example of oil, that represents about 40% of the world energy supply in this early 21st century : in Saudi Arabia, it just requires a couple of dollars to exact a barrel of oil, that is 3 cents per litre, or 0,3 cent per kWh ! (there are about 10 kWh in a litre of oil). It’s much cheaper than mineral water, and much cheaper than any litre of biofuel, if we only consider production prices, of course, because oil has to be transported, refined, and is subject to fees paid to producing countries and taxes paid to consuming countries. It is also 20 times cheaper than wind power, that today costs 5 cents per kWh in rough figures.

To lower the market price difference between fossil fuels, so cheap to produce today, but whith heavy future costs associated to their use, and renewable energies that often have higher production costs, or that require more investments, there are two solutions :

- Grant subsidies to renewable energies, to encourage their production and/or consumption, within the limits of their physical possibilities, of course, because these latter are – in the short run – much lower than that of fossil fuels,

- Increase taxes on fossil fuels, to discourage their consumption, what then makes energy savings, renewables, and… nuclear (but it doesn’t bother me !) more and more competitive.

The most commonly heard opinion is of course the first, because of this “confiscation” feeling that is always associated to a tax increase, and because we would like to believe that it is possible to increase subsidies without raising taxes and without decreasing other budgets. Of course, this is wrong :

- Subsidies increase a little more the federal budget’s expenses, and thus the possible deficit, when taxes increase the revenues,

- Increasing taxes requires a human intervention only to manage exceptions, when subsisdies require a human action prior to any money giving (it’s therefore much more time consuming for equivalent sums managed) ; in other terms with a higher tax discussing a particular case is an exception when with subsidies it is the general rule,

- without changing the tax wedge on fossil fuels, subsidies to renewables do not grant at all that there will be no consumption transfers. For example, if we subsidize solar heaters, and that the plumber uses the extra revenue to fly more, it is not exactely fitting the general purpose !

- it is more generally speaking much easier to subsidize renewables if we have first extra revenues to do so, by increasing… taxes on fossil fuels !

What could be done with the extra money obtained with an increase of taxes on fossil fuels?

People often forget a major difference between an increase of the market price of oil, and a tax increase, because from their end-user consumer point of view it has similar effects in the short run : tax is a national redistribution, with money that doesn’t leave the country, when a market price increase of oil is a net impoverishment for a consuming contry, since money is leaving for abroad. As we have seen above, letting oil market prices increase sharply creates unemployement, when there is no evidence that raising taxes has a negative effect on the economy of the country as a whole. We should not forget that if fossil fuel prices are voluntarily increased, it provides additional resources for the federal budget, that, as we have seen above, desperately needs it in most occidental countries, and will spend the additional money in the country, creating national activity “elsewhere”.

We can even say more : without an increase on fossil fuels, the federal budget will never have the necessary resources to finance ambitious plans to change production and consumption related infrastructures. With the money resulting from an increase of taxes on fossil fuels (all fossil fuels ! gasoline indeed, but also natural gas, domestic fuel oil, diesel oil, heavy fuel oil, jet fuel, coal…) we could precisely finance investments that would help to lower the fuel consumption :

- a massive insulation plan for homes and offices, that use 25% of fossil fuels in France (heating and sanitary hot water for the most), without forgetting a preventive insulation against future summer temperature increase, otherwise the summer electricity consumption will sharply increase. As long as the opinion is “mild” – or cold ! – on nuclear electricity, it means more gas fired power plants, necessarily vulnerable to the unavoidable gas depletion, and contributing to an increase of CO2 emissions, CO2 being the main greenhouse gas emitted by man. Let’s recall that wind power won’t produce enough, and by far, in front of such an evolution.

- Financing a number of “small” training or information initiatives, that are not sufficient to generate large savings, but allow to make the effective measures – which are economical – socially acceptable : improvement of the training of journalists to make them attentive to the physical limits of the world, financing a better training for engineers to allow them to evaluate the energy consumption generated by any project or infrastructure, financing a better training for the future high ranking civil servants so that they know what it is about regarding energy instead of considering the world as infinite, financing general information for the public through energy labels on anything that uses some (including buildings), financing studies so that the local economy doesn’t get based on airborne tourism or any other activity highly dependant on fossil fuels, etc ; finding ideas is not a problem!

- helping a change in the transportation infrastructures and habits :

- helping productive activities to shorten their supply chains and produce as close to the markets as they can, knowing that with the present good flows it is out of question to replace trucks by trains (or cars by buses), and that the present mobility, oil-dependant for more than 90%, is probably not sustainable,

- increase of railways to put on trains, still, what can be drafted from road transport,

- helping truck drivers to progressively find another job,

- helping to “de-megapolize” major cities, in order to get anew numerous but small and dense cities, what allows to decrease the amount of energy used for daily trips, and allows also to decrease long distance road transport for supplying these large cities,

- progressively modify cities to include bike lanes, better buses or underground, larger sidewalks, and… less moving !

- helping the development of some kind of telework (not going by place once a week to the office, obviously), to decrease heated – and air-con – offices, and daily commuting,

- etc.

- a selective help to some industrial sectors to help them to change (without luring ourselves : our level of material consumption, given the energy it requires, is probably not sustainable), to help them shift from fossil fuels to other forms of energy whenever possible (for example iron ore could be transformed in iron with hydrogen, produced by a small nuclear plant next to the steel mill, but it will be more exxpensive – and more capitalistic – than using coal).

More generally, is the name of the game is really to cut the French greenhouse gases emissions by 4 by 2050, as our Prime Minister declared in a speech given in 2003 (and many other occidental leaders, european heads of governments or, believe it or not, governors of US states), it means that the oil and gas consumption must follow a 2,7% per year decrease from now on. It is totally impossible to get there voluntarily without any action on prices, and not achieving voluntarily a strong decrease of our fossil fuel consumption before 2050 os most probably signing for an unwanted decrease, most certainly before 2100, and most certainly much more unpleasant than a progressive raise of taxes…..

Is it possible to increase taxes in fossil fuels without increasing the tax wedge?

Let’s first recall that there is no direct link between a high tax wedge and a weak economy (see above). Still, as the population does like to hear about tax increases, sometimes wrongly as we have seen, some economists favourable to higher taxes on energy have written that the good thing to do would be to raise taxes on energy while decreasing taxes on work, to keep a constant tax wedge. It is of course theoretically possible, though social charges are affected (they can be used for only one thing : social security contributions to pay for health spendings, pension contributions for retired people, unemployement contributions for jobless people, etc), when taxes on energy (VAT or TIPP) go into the federal budget where they can be used for “anything”.

If we lower social charges, it will create a deficit for the corresponding organisms (health, retirement, unemployement) that the federal budget will have to compensate. If we lower social charges for exactely the same amount that we raise taxes on energy, in order to favor manual work and deter energy use (and therefore machine use), we will get the desired effect on hydrocarbon consumption, but without getting the additional resources required to subsidize alternative solutions if necessary, except if the general hierarchy of the federal action is changed (for example bulding less roads will spare money otherwise devoted to road construction), which is of course always possible.

So three directions can be investigated :

- increase taxes on fossil fuels to progressively decrease itss usage (let’s recall that to keep a favourable climate, we need to leave underground most of coal, and possibly a significant fraction of oil and gas) ; the proper way to do so being, in my opinion, to increase these taxes by a couple % per year, indefinitely, from now on,

- lower social charges, but at most for the amount of the extra taxes on energy, the ideal being to share the extra revenues between a lowering of social charges and a diminution of the long term debt (and secondarily we must imagine the mechanism allowing to transfer part of these revenues from the federal budget to the social organisms), and without forgetting that the more the energy consumption lowers, and the more the fiscal revenues associated to this consumption lower,

- modify the spendings allocated to each ministry, to get ready for a more sober society, and not the opposite, for example by decreasing the budget allocated to road construction (which is not illogical if we intend to have less road transport…) and increasing the budget allocated to insulating buildings.

Is it possible to “do this” to modest people?

This is a question for those that did not read what is above ! Because the alternative is not : either we raise taxes, and gasoline becomes more expensive, or we do not raise taxes, and gasoline remains cheap forever for “modest” people. If we do not voluntarily deter fossil fuel consumption, can we plead that “modest people” will be spared by the above mentionned consequences ? When the next oil shock happens, won’t it be the “modests” that will suffer first from a raise of unemployement, that has always followed an increase in the market price of oil for the last 20 years ? If “modests” have remained heavily oil consuming, where is the solution when it is geology that will lead to price increases ? If climate change becomes major, won’t they be more vulnerable than “riches” that will have the means to adapt or move elsewhere ?

Future oil or gas shocks, unavoidable if we do not undergo a “cure” to decrease our consumption faster than geology will do it for us, can certainly generate major social destabilization. Well, when a society is brutally destabilized, for example when experiencing a major recession, aren’t the “modests” the first to suffer ? Where is the argument allowing to consider that an unwanted decrease “later” will do no more harm – and will do it later – than a voluntary decrease today ? Isn’t it preferable, for “modests”, to undergo a progressive rise of the price of fossil fuels today, that leaves time to adapt without much suffering (but most certainly with much protestation !), rather than becoming unemployed, stangled by a brutal increase of everything (since there is fossil fuels in anything, including food !) or having to pay for the consequences of climate change, later on, with an upper limit of damages no one can set ?

In many aspects, the debate on taxes on energy is much alike that on tobacco : it would be injust to raise prices because it would harm the purchasing power of “modest” smokers. But the name of the game was also to deter “modest” people from smoking ! Incidentally, just as for oil, it will precisely be “modest” people that will suffer the most, afterwards, of the consequences of tobacco, because thay have a lesser access to high quality medical care.

At last, even if it is not politically correct to say so (but I don’t care : I don’t intend to run for whatever office !), one should recall that “modesty” doesn’t exist any more when we consider physics. The sad truth is that, given the limited possibilities of our planet to supply resources, including non renewable ones, and its equally limited ability to process our waste or cope with the consequences of our activity in the long run (such as climate change), it is not only the lifestyle of a Rockfeller which is not sustainable, but also, alas, that of “Mr. – or Mrs. – everybody” in any occidental country. Any factory worker, cashier, or city employee has a standard of living way over what our planet will be able to stand for a very long time. No ideology or morals here, just facts, and facts are stubborn : when we choose to ignore them, what we get is generally worse than when we accept them.

What about the competitivity of companies?

That’s another question for those that didn’t read the upper part of the page ! Who can reasonably argue that the economy will not suffer in case of a brutal increase of energy prices (which is exactely the case for oil), and that a progressive price increase will not be much easier to manage for productive activities ? That expensive energy is a bar for human activity is another common idea that no evidence supports : the effective result is “something different”. High energy prices do not harm the economy if it has always been so or if it happens progressively, but a brutal increase definitely has a negative effect if the economy is used to low prices. Is the automotive industry in a bad shape in France because we have important (though not sufficient !) taxes on gasoline ? No : it just manufactures smaller cars (that sell very well abroad). The “delocalization” threat, though perfectly real in a restricted number of cases, is globally not a problem : most of the economic activity is perfectly “localized” in France and unable to be moved elsewhere..

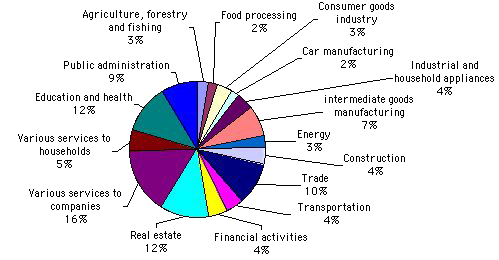

Share of each activity in the french GDP in 2003.

It seems hard to delocalize a major share of agriculture, public spendings (administration, education, health), the vast majority of services to individuals (child keeping, cleaning…) and to companies, real estate (selling estate in France, still !), most of transportation, most of retail and distribution, most of energy (gasoline pumps and power plants are not to be moved outside France very soon !), construction, and actually most of the industry.

Source : INSEE/Comptes de la Nation, 2004

Besides, changing the rules generates loosers, but also winners, which is coherent with something stated above : there is no link between the tax wedge and the GNP per capita in the OECD countries. The GNP is the classical indicator to measure wealth, even though there would be much to say on it. Taxes are a redistribution, not a confiscation, and the more taxes people pay, the more companies will supply the state and the more families will get their income from it, afterwards spending it in goods and services. The suppliers of the state and of the civil servants certainly contribute to “fueling the economy”.

If we raise taxes on hydrocarbons, domestic fuel oil suppliers and gas suppliers will sell less, but construction companies will sell more insulation panels and double glazing, with materials that will have to be manufactured by industrial companies. Are we sure that the economy as a whole will suffer from such a change ? Probably much less than from an oil shock if the prices were previously low ! We should also recall a major advantage of taxes when they are based on volumes and not on prices without taxes (such as the french TIPP) : it considerably softens the market price variations for the end user. It therefore remains constant – by litre – whatever the price of the gasoline without taxes. As it represents about 65% of the price without taxes (gasoline also supports VAT, which is proportional to the price with all the other taxes), here is what happens for the end-used if the price of gasoline “out of the refinery” (that is without taxes) doubles (the inital price has been set to 1 euro per litre) :

| Gasoline price (€) | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| Price without taxes - out of refinery | 0,20 | 0,40 |

| TIPP | 0,63 | 0,63 |

| TVA | 0,17 | 0,20 |

| Price at the pump | 1,00 | 1,23 |

What happens for the end-used if the price of gasoline “out of the refinery” doubles?

Clearly, if the price out of the refinery doubles, the car user seens only a 23% increase. In other words, the higher the rate of TIPP, and the more we are “unharmed” by market price increases for gasoline. Of course, this reasoning also applies to gas (that will experience brutal increases of market prices for sure), and even to coal !

What seems “heretic” in the short run, since it increases production costs, is actually an excellent warranty in the long run, as soon as we accept the hypothesis of a supply that will decrease whatever way we look at the problem.

A small conclusion…

As a result of all what preceeds, the best thing that any occidental government could do for us, to avoid (very) unpleasant evolutions in the future, particularly for “modest” households, would precisely be to raise progressively the prices of non renewable energies through a tax increase, to get progressively “unaccustomed” to oil that will anyway be less abundant one day, and to avoid that coal is used as a substitution, what would generate a “climate shock”. I personnally will vote for the first candidate that promises to raise the taxes on fossil fuels by 3% every year, starting when he enters the office, and lasting forever !