The IPCC published as soon as 1996 the following statement: in order to stabilize the CO2 level in the atmosphere, that is to halt the increase of the quantity of CO2 in the atmosphere, whatever the stabilization level is, and whenever we achieve stabilization, human emissions must necessarily be cut by two at least compared to the 1990 level.

Why is that ? It’s arithmetics, stupid: in 1990, the world emissions amounted to 6 billion tonnes of carbone per year (that is 22 billion tonnes of CO2), and Mother Nature knew how to take 3 back (each year also), through what is called “sinks” (oceans, terrestrial ecosystems). If the carbon cycle manages to remove only 3 GtC per year from the atmosphere while we put 6 in there, it’s no big deal to understand that the other 3 remain above our heads. In order to stop the increase of the atmospheric CO2, we must cut our emissions by two.

Actually it’s a little more complicated – and the ultimate goal is even lower – but let’s say that that dividing the 1990 emissions by two gives the magnitude of the challenge.

A more ambitious ultimate goal

To stop the atmospheric CO2 increase, the principle is very simple: the human induced emissions must remain below what the “carbon sinks” (oceans for one part, continental ecosystems for the remainder) can take back.

But this uptake is not constant. Today, in absolute figures (that is in billion tonnes of carbon), this uptake evolves the following way :

- it increases with the amount of CO2 in the air for continental sinks : an atmosphere that contains more CO2 favours, in the short term, the growth of plants,

- it increases with the amount of CO2 in the air for the ocean: the amount of CO2 that dissolves in sea water increases if the air contains more CO2 (physicists say that the partial pressures of CO2 in the air and in the water come to an equilibrium: if it increases in the air, it increases in the ocean also),

- but, for continental sinks as for oceanic sinks, this absorption decreases with temperature: a warmer water dissolves less CO2, and in a warmer climate the surplus of growth of the plants (if it remains) compensates less and less an accelerated decomposition of the soil carbon, that puts CO2 in the atmosphere. As the temperature is bound to rise in the future wathever we do (but it will increase more or less depending what we will do, which is not a minor difference !), sinks will weaken with time, even when our emissions are stabilized.

The consequence of the latter is that dividing our present emissions (world emissions, of course) by two would allow to equal the present absorption capacity of natural sinks, but we will have to go even lower afterwards, because sinks will weaken with time (a possible catastropha being that sinks turn into sources if we did not decrease our emissions fast enough).

But to simplify we will say that a first step objective that is meaningful for the physicists is to divide the 1990 world emissions by 2.

Caution ! When the CO2 concentration stops to increase, it does mean an immediate decrease of the additional greenhouse effect (compared to the preindustrial situation, in 1750) and even less a fast decrease of the world average temperature. It just means that this additional greenhouse effect stops to increase, but the atmosphere will remain for millenias at least with a stronger greenhouse effect than in 1750. To avoid as fast as possible a significant future change, a division by two of our emissions is more a minimum than a sufficient objective.

Let’s get back to figures: in 1990, our CO2 emissions amounted to 6 to 7 billion tons of carbon (often noted 6 to 7 GtC, G standing for the prefix “giga” that means a billion in the scientific notation). So independently of what was decided in Kyoto, a goal that has a “physical” meaning for the world is to get down to 3 Gt per year at most. 3 GtC for 6,5 billion human beings (about to become 7 to 9 in 2050) means, if we equitably allocate the “emission right”, 460 kg of carbon (that is 1,7 tonne of CO2) per person and per year

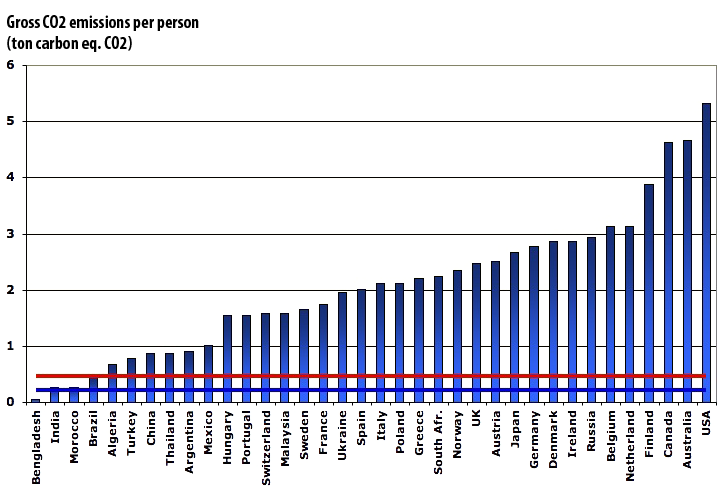

As this figure of 460 kg of carbon or 1,7 tonne of CO2 won’t mean much to most people (!), to make it meaningful we must compare it to present emissions – actually those of 2003 – for a number of nationalities on the planet. Indeed, this 460 kg carbon equivalent “quota” per person and per year represents :

- less that 10% of the emissions of an American, an Australian, or a Canadian, that should therefore divide their emissions by more than 10 to achieve their share to stabilize the atmospheric CO2,

- Between 15 and 20% of the emissions of a German or a Dane (Danish are among the highest CO2 emitters per inhabitant in the EEC), that should therefore divide their emissions by 5 to 6 to achieve their share of stabilization,

- 20% of the emissions of a Briton, individual emissions in Great Britain shoud therefore be divided by 5,

- about 25% of the emissions of a French or a Swiss (or a Swede), which means that a division by 4 is required here,

- roughly 30% of the emissions of a Portuguese, for whom a division by 3 is then the objective,

- roughly 50% of the emissions of a Mexicain, a Chinese or an Argentinian, which means that these countries, as “poor” as they may be considered, are already way too “rich” as far as CO2 emissions are concerned…

- But 1,5 times the emissions of an Indian or 4 times that of a Nigerian: some countries would still have the possibility to emit a little more…

CO2 emissions per person from fuel combustion in 2003(in blue getting darker to the top)

The “maximum allowance” of 460 kg of carbon per person and per year, which is the goal if we want to divide the CO2 emissions by two, assuming we remain 6,5 billion people on earth (in dark red)

The same “maximum allowance” per person and per year if the goal is to divide the CO2 emissions by three, assuming we become 9 billion people on earth (in dark blue)

Even the Chinese are already over both limits, and we can summarize the problem by saying that “sustainable development” is about the present level of an Indian.

It is obvious that the present “carbon economy” is not compatible with the preservation of climate.

Sources : WRI, from AIE and UN, 2009

With the technologies currently in use, the limit comes fast, since this “maximum allowance to emit without harming the climate” (of 460 kg of carbon or 1,7 tonne of CO2) reached as soon as we have done just one of the following:

- make a return trip from New York to Paris (by plane, not sailing !),

- or consume 3,700 kWh of electricity in Great Britain (or 3,000 kWh in the US), but as much as 24.000 kWh in France (thanks to nuclear energy, but shhh, it is not politically correct to say so…), knowing that each French consumes around 8.000 kWh per year today (of which 50% is “invisible”, because it is electricity “embedded” in the manufacturing of the various goods – including food – that we buy).

- or buy 50 to 500 kg of manufactured products (that is the third of a subcompact car, less if there is a lot of electronics or rare materials).

- or use 2 tons of cement (a modern house of 100 m2 – roughly 1000 square feet – requires 10 tons),

- or drive 6.000 km – that is 3100 miles, roughly – in jammed urban trafic in a small subcompact car, that is 6 months of driving – on average – of a Paris inhabitant,

- or drive, still in jammed urban trafic, only 2,500 km – less that 2,000 miles ! – in a SUV or 4×4 or Hummer or any gas-guzzler alike,

- or use 7.200 kWh (that is roughly 20,000 cubic feet) of natural gas (that it a couple months of heating of a house).

If we take into account the other greenhouse gases, 460 kg carbon equivalent is emitted as soon as we have:

- fled from Paris to New-York without coming back,

- or eaten 90 kg of beef (meat with bones) or drank 1.400 liters (that is roughly 3.000 pints) of milk (that we mainly consume…through ice cream, cakes, cheese, butter, etc…). The mad cow disease was excellent news for climate change !

We need to go back to stone age, then ? Well, there is some room between nowadays and the stone age…. It must be noted that the often heard speech on the “right to development” ignores a basic fact: even a modest Indian of the 21st century lives considerably better than an Occidental of the 10th century. A french peasant of that time had only his two arms and a little wood to heat his – one room, sometimes two – house, when a modern Indian has, through his even modest energy consumption, the equivalent of 10 to 20 slaves at his disposal, not to mention that he lives 2 to 3 times longer (in Europe our energy consumption equals to 100 to 200 slaves each: not bad !).

Anyway, this level of 50% of the emissions of 1990 is “not negociable”, because it is the consequence of a basic fact: extractible fossil fuel is in finite amounts. The only good question is therefore : do we do it voluntarily, or do we wait for non wished events to do it for us, probably in much worse conditions ? Whatever way we will get there, the delay that will be taken to divide emissions by two just conditions:

- the level at which we will stabilize (1,5 to …. 4 times the preindustrial CO2 concentration, if not more), and therefore the ultimate temperature rise (over 10 °C cannot be excluded today),

- the delay required to achieve stabilization (less than a century to several centuries).

It is also interesting to note that this “low carbon” goal has also advocates in “developping” countries. It was the case, for example, of the late Anil Agarwal, Head of the Center for Science and the Environment, in an interesting article that I put online here.

Actually, not only is this maximum of 50% of the 1990 emissions non negociable, but it is probably still too high: the conclusions of the IPCC present this division by two as a minimum requirement, but to achieve quickly a “low” level of stabilization (say 450 ppm) it is even more that is required..

Suppose now we need to divide by 3 the world emissions, what will be a goal some day anyway. If, in the same time, the world population has risen to 9 billion people, it means that each of us will be entitled not any more 500 kg but 2/9th of ton per person, or roughly 250 kg of carbon equivalent per person and per year. That is 10% of the present emissions of a French, and 3% of those of an American. We have plenty of work on hand !