It is frequent to hear that everybody drives because public transportation is not appropriate, and that if the government condescended to put money in there we would all be able to leave our cars in the garage. Unfortunately, reality is not that simple : whoever looks at the available figures realizes that it is no longer possible, at the present level of mobility, to consider that train is a valid alternative to cars and trucks. It could only absorb a marginal part of the car trafic.

In 2001, the passenger trafic by car, in France, totalled roughly 700 billion passengers.kilometre, and the rail passenger trafic amounted to a little less than 100 billion passengers.kilometre. The loading factor of trains is 33% on average. It may seem low, but it includes commuting trains at 10h30 in the morning and 13 h on sundays, the night train going from Paris to Bordeaux on week days, etc.

Let’s suppose that we manage, through a clever organization, to entirely fill all the existing trains. This would withdraw only 200 “small” billion passengers.kilometre from cars, that is 25% of the present trafic in rough figures. Even going from 33% to 50% for the loading factor of trains, that would probably represent an outstanding performance, would allow “only” a less than 5% decrease of the car passenger trafic.

Actually, better filling the trains than today would require heavy reorganizations of our present world. Here’s an example : in order to have loading factors for the commuting trains that remain constant (and high) thoughout the day, it would require that the starting hours for the working population be evenly distributed between 7 am and 12 or 13 pm. Otherwise, the operator has to dimension the means according to the peak hours, and then the infrastructures are only partially loaded for the rest of the day. The same reasoning applies to main train lines, used at full capacity only at some periods of the year or hours of the day, etc.

Let’s now assume that we wish to build new capacities to substitue 100% of the passenger car trafic, that takes mostly place in low density urban areas (suburbs and rural areas). A loading factor of 33% would then be a maximum, as the loading factor of the commuting train averaged on the whole day is closer to 20%. It means that, to meet this objective, it would be necessary to multiply the number of circulating trains by 4 at least, and in my opinion by 10, with a fivefold to tenfold increase of the infrastructures (because the new infrastructures would serve zones less dense than the ones presently served).

This quick calculation shows that, on a global scale, assuming that an increase of railways is a prerequisite for giving up cars is equivalent to considering that we will never give up cars on a voluntary basis. Still, the individual gasoline powered car will have an end : fossil fuels are not eternal, and the “solutions” sometimes put forward – electric car, fuel cells – actually only constitute a displacement of the problem (generating electricity or hydrogen without fossil fuels).

Declaring that we will give up cars at the only condition that there exists a satisfying offer of railway public transportation is therefore getting ready to give up cars for…nothing. Sticking to such a point of view will never allow us to envision with serenity – and time in front of us – an ineluctable decrease of the individual mobility, and will never allow us to adapt accordingly our urbanism (have numerous but dense cities, allowing to be supplied in food and from the close neighbourhood) and our conomic activities (produce locally, work close to home, etc).

Of course, all this doesn’t mean that trains are uninteresting. But thinking that we may let a civilization “based on car” develop without limits because, when the day comes, we will be able to substitute all this road trafic by railway transportation is alas an illusion.

Then what about buses?

That’s fine, some will say, we just have to put buses everywhere ! Actually, a large part of the previous reasoning applies also to buses : they are frequently loaded all year long at a small fraction of their capacity, and it is just during some rare peak hours that they are full up.

Let’s take the example of a housing lot in the suburbs. To justify a bus passing by every 15 minutes, it is necessary that 5 to 10 passengers get in the bus at the stop, in average. If the bus operates 16 hours a day (7 to 23 hours, for example), this represents a minimum of 16*4*5 = 320 passengers. If several directions have to be served, and if there is a bus stop every couple hundred metres (what is probably required to fit the “minimal public transportation” definition of most people using cars that would lead them to take the bus instead), it supposes so many times 320 passengers coming from several hectares (reminder : an hectare is a square 100 m wide).

Well, in the suburbs, where most people live in houses, there are about 20 houses per hectare (if the average land for each house is 500 m2, that is 5000 sq acres). If there are 5 people on average per house, this means that the population density in the suburbs is around 100 people per hectare. Where on earth will we find the several hundred passengers required to operate a bus service with a minimal density ?

Besides 20% only of the car trafic (in France) corresponds to commuting to work : the rest is for driving kids to shools, shopping, going on holidays or to places of leisure, etc. Coming back home after shopping, or with the kids, by bus is definitely possible, but the rate of substitution on the existing bus lines surely not amounts to 50% of the existing car trafic.

We find here also a “dead end” linked to the fact that we have adapted everything, or almost, to an abundant car based mobility, and the impossibility to switch quickly all the car trafic to public transportation is not only the consequence of a supposed bad will : it also proceeds from basic mathematics. Does it mean that cars will remain “forever” ? No : “oil mathematics” (and “electricity mathematics“) also forbid that one or two billion cars circulate around for eternity. It just means that “one day” people is low-density susburbs will pay higher and higher prices for their daily transportation, and that hoping that “convenient” public transportation will appear outside the dense heart of cities is just like waiting for Santa Claus in most cases. Spreading suburbs didn’t exist before cheap and abundant energy, and will slowly disappear – as satellite of inner cities – when energy prices rise. We might choose to provoke this evolution voluntarily, through taxes, or do it unvoluntarily, as a consequence of the laws of physics applying to a limited world, the latter bearing all all the risks linked to social “going down” happening rapidly and unwillingly.

Could we put all trucks on trains?

As frequently as for cars, some individuals affirm that if “companies” also condescended to it, we would be done with trucks that stink and make too much noise. Then what ? In 2001, goods transported by trucks totalled 200 billion of tonnes.km (source : statistical service of the Ministère de l’Equipement), when trains realized 50 (source : SNCF).

Shifting all road trafic to trains is here as much of an illusion than it is for passenger trafic as long as the present flow of goods is constant. The first observation, indeed, is that most goods that are on trucks don’t travel very far : 3/4ths of the tonnes charged travel less than 150 km.

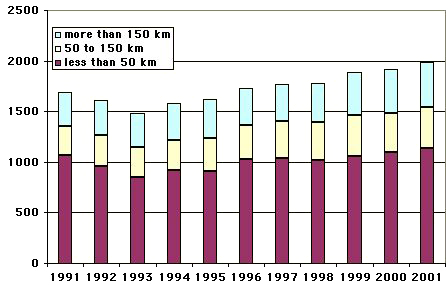

Millions of tonnes transported per year (in France) depending on the distance travelled.

Source : Ministère des Transports, DAEI-SES

Knowing that places where goods are charged (for example a plant, or a farm) or delivered (a supermarket, another plant, a slaughterhouse or…your home) won’t be close to a railway very often, using trains for most of the short distances seems difficult to implement.

This being said, if we examine trafic and not weights charged (knowing that trafic = weight x distance), there is a “large chunk” consisting in long distance transportation, where substuting trucks by trains is not necessarily a stupid idea.

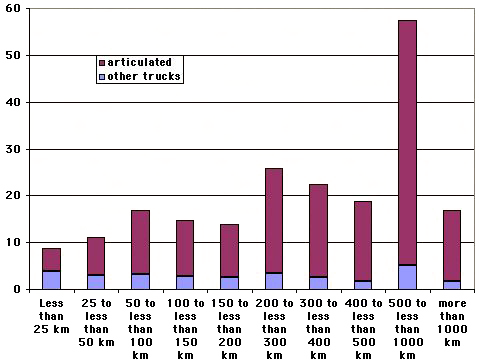

Billions of tonnes.km in 2001 depending on the distance travelled and on trucks used.

Source : Ministère des Transports, DAEI-SES

On the above graph, a large part of the trafic for distances over 500 km (which represents 25% of the total) is probably switchable to trains, and to river boats for a small part (see below), but there it stops in the world that we know.

In other words, 20 à 25% of the truck trafic can be substituted by trains, provided we increase the existing capacities by 50 to 100% (including railways dedicated to freight trains), according to the SNCF. But to divide the number of trucks on the roads by 10, we must shorten the distances travelled and the diminish the flow of goods, hence the flow of products of all nature that we are today delighted to find in supermarkets : it’s maths !

And why not load everything on river boats?

River boats represented, in France, 7 billion tonnes.km in 2001 chen trucks amounted to 200. Is an additionnal comment required ? As long s the flow of goods is what it is today, there is not much to hope from there.

Conclusion

It seems likely that the present truck and car trafic will decrease “one day” in the coming decades, as no alternative exists that would allow to substitute a large part of this trafic by “something else”, and as maintaining the present situation forever is not compatible with what we know of the world today :

- fossil fuel reserves are not eternal, hence the consumption of road fuels will decrease in the long run even after a transcient phase of increase,

- the fuel cell and the electric engine only consist in displacements of the problem,

- biofuels are totally unable to replace oil at the present level of consumption,

and at last CO2 emissions will necessarily decrease enough “one day” so that the atmospheric CO2 concentration stops rising (because the amount of CO2 in the air can’t rise indefinitely),

Therefore, if a decrease of the present flow of goods does not result from a voluntary decrease of the tonnes.km (shortening of the distances, decrease of the weights transported), it will result from a unwanted event (recession, war, or whatever consequence of climate change), as the option “everything goes on as today for an illimited duration” isn’t available.