Unfortunately the answer to this crucial question is no.

Indeed, we have seen that the lifetime (or more exactely the residence time) of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is very long, particularly for the principal among them, the carbon dioxide (CO2), which remains for a century in the air.

If we totally stop the emissions tomorrow morning (including respiration !), it would only lead to stabilization of the atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases at the present level, before a slow decrease of these concentrations.

Well, these gases still enhance the greenhouse effect as long as they are present, that is for centuries. Wathever we do today, the “heating” derived from the gases that man has already put in the atmosphere since 1750 will go on for centuries.

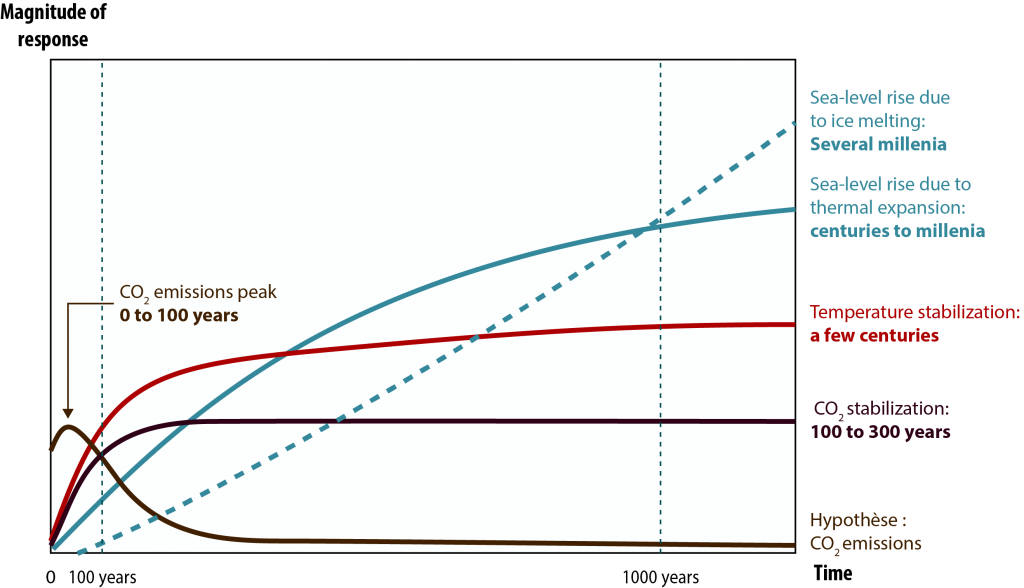

And if we look at the consequences of this additionnal heating, they may even take several millenia (diagram below).

Illustration of the non compressible delay that takes place between the peak of CO2 emission (brown curve at the bottom of the figure, that cuminates in 2050 on this example) and the peak of the consequences : temperature rise goes on for centuries after CO2 emissions have decreased, and the sea level continues to rise for millenia thereafter.

Should the CO2 emissions peak later, all the curves would be shifted to the right, but the general train remains the same. And of course the magnitude of the responses of the climate system (vertical axis) is strongly linked to the level at which CO2 stabilizes, and therefore the time at which CO2 emissions peak and the magnitude of the peak.

Source: IPCC, 2001

Because of this considerable inertia of the climate system, the evolution that we have put in motion will have consequences for millenia from now on whatever we do in the future.

Nevertheless, it is still in our hands to choose between a stronger or a weaker perturbation, a change of climatic era or maybe a “simple” and manageable change within the present era. In other terms, the moment at which we start to decrease the emissions and the rate of decrease have a very significant impact on the maximum average temperature that we will experience, and the rate of temperature increase.

And, at last, there is no known – or even conceivable – process that would allow to remove quickly the surplus of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. The natural carbon sinks (terrestrial ecosystems, ocean) operate at low speed (and are accounted for in the climate models), and it is not thinkable to “filter the whole atmosphere” to remove gases that are present, for some of them, at the concentration of 0,000000001% !

There is a first conclusion that may be drawn from the graph above : as the world is finite, it is absolutely certain that the atmospheric CO2 concentration will eventually stabilize, whatever level will be reached then. Indeed, supposing that it will never go through a maximum is equivalent to supposing that it will indefinitely rise, what is not compatible with a finite world.

So as it is certain that this CO2 concentration will stabilize “some day”, it means that it is also certain that the emissions will go through a peak “some day”. And if there is a peak, there is a decrease after the peak, that’s mathematical ! In other terms, wish it or not, CO2 emissions will eventually decrease “some day”, because the world is finite, and our choice is not between “painfully restrict ourselves” and “have all we want forever”, but between “choose the moment and rate of decrease” and “wait until the decrease happens anyway”, with the risk, in the latter case, that the decrease is caused by a catastropha whatsoever. History tells that the sooner we undergo – or prepare for – a change that will happen anyway, and the better we are.

What if we do nothing ?

But there is another conclusion that may be drawn from the graph above : let’s imagine that the decrease of the CO2 emissions is not a consequence of our wisdom, that is the consequence of a voluntary limitation of our consumption, but the simple reflection of a shortage of fossil fuels, because we will not have been able of stopping before.

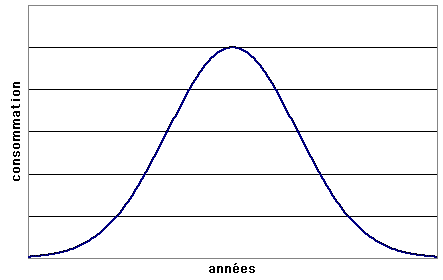

Indeed, the CO2 emission curve (in brown) of the above figure looks exactely like the curve of the consumption of a limited natural resource, rising then falling under the effect of a progressive shortage (below).

General aspect of the consumption of a non renewable resource with time.

At first it rises fast (discovery of new deposits, fast amelioration of the techniques, demand growing quickly…) then the rise slows down under the effects of a price also rising, as a result of a progressively increased difficulty to recover the resource (deposits with a lower content of the resource) and then comes the day of decline, under the effect of the rarefaction of the resource, in spite of always improving techniques.

Any ore extraction in a given country corresponds to that curve (not always that smooth and perfect, of course, but the general aspect remains). Oil production in the US, for example, rose, then went through a maximum 30 years ago, and now declines, the whole curve being well bell-shaped.

If this curve is applied to the fossil fuel consumption of the whole planet, the CO2 emissions will look alike, of course.

What happens then ? The figure on the top of this page can then be interpreted the following way :

- first we undergo the effects of the shortage, that is the effects of a non wished decrease of the consumption when we were not prepared for (otherwise it is not a shortage !), what is likely to generate a couple of unpleasant starts,

- in spite of this decrease of the emissions resulting from the shortage, the atmospheric CO2 concentration goes on rising for a century, more or less,

- and most of all the average temperature goes on rising quickly for more than a century after we pass the CO2 emission peak. In other terms, the magnitude of the consequences keeps increasing, while our possibilities to adapt, in first approximation proportional to the amount of available energy, might decrease, because of the shortage in fossil fuels (the unknown parameter is non fossil energy, of course).

Clearly, if we wait for a shortage in fossil fuels to limitate our emissions, we take a serious option to find ourselves in a situation where the problems will increase on and on (because the climate will be more and more perturbated) with less and less possibilities to face them. Here’s a situation we might want to avoid…