Why do I feel like advertising this tool ?

Because I am one of the authors, and that no-one is better served than by oneself ! Of course, in addition to the informations that are featured on this page, you can (and even should, if you read French…) take a look at the website of ADEME dedicated to the Carbon Inventory.

Should any company bother about its greenhouse gases emissions ?

It is quite frequent to consider that greenhouse gases emissions have only two causes, and hence that only two categories of activities should bother: industries and transportation companies. From there, a butcher, a bank, a travel agent, a hotel, or a police station would not generate significant emissions, and any action plan might as well forget these actors of the economic or social life.

Alas, reality is much more complex. Today, any human activity, whatever it is, generates direct greenhouse gases emissions, even an insurance company or a kindergarten. There are in addition “indirect” emissions, linked to the production of the goods or services required to “run the business”, and that can be much more important than the direct emissions.

Let’s start by the main greenhouse gas, the carbon dioxide. Some is sent into the atmosphere as soon as we burn a product containing carbon: coal, oil, natural gas….or plastics, which is nothing else than transformed oil. Hence we will find greenhouse gases emissions:

- as soon as a fossil fuel (coal, natural gas, or any oil product) is burnt, be it to move (by car, place, train if applicable, or boat) or to heat a place (in France, heating houses and offices lead to larger emissions than those of cars),

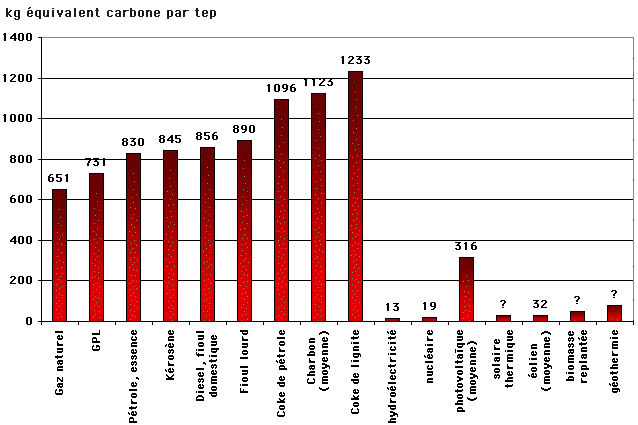

Kg carbon equivalent emitted by tonne oil equivalent when using various energies (1 tonne oil equivalent = 11.600 kWh = 42 billion Joules).

Fossil fuels are all on the left, starting from natural gas to lignite coke. When the primary energy yields only electricity (hydroelectricity, wind power, nuclear energy) the figures correspond to the consumption of 11.600 electric kWh (final energy basis).

At last the question marks mean that I have a vague idea of the rough figures (corresponding to the height of the bar) but no precise figures.

- when one burns waste containing plastics,

- to “produce” electricity from fossil fuels (which represents only 5% of the electricity generation in France, but 70% in the US, 50% in Europe, and more than 80% in Poland or Denmark),

| Energy source | CO2 Emissions in grams per kWh |

|---|---|

| coal | 800 to 1050 |

| Natural gas (combines cycle) | 430 (average) |

| nuclear | 6 |

| hydroelectric | 4 |

| wood | 1500 without replantation |

| photovoltaïc solar | 60 to 150 |

| wind power | 3 to 22 |

Source : Jean-Pierre BOURDIER, La Jaune et La Rouge of May 2000

- to produce raw materials (a lot of fossil fuel is required to produce steel and metals, plastics, glass, concrete…)

| Material | kg carbon equivalent per tonne produced (european values) |

|---|---|

| Steel | 300 to 850 depending on % scrap steel |

| Aluminium | 600 to 3.000 depending on % scrap aluminium |

| Flat glass (window glass) | 400 |

| Bottle glass | 120 |

| Plastics (polyethylene, polystyrene, PET...) | 500 à 1.600 |

| Paper-card | 300 à 500 |

| Cement | 250 |

Source : ADEME, 2003

- in agriculture, that uses energy (for machinery), and that generates emissions of other greenhouse gases than carbon dioxide, through cattle raising (cows, goats, sheep), and fertilizer use.

- wherever there is putrefaction (for example when food waste is dumped in a landfill),

We can infer from this list that any human activity, whatever it is, generates direct and indirect greenhouse gases emissions. The indirect ones, that are “included” in the goods or services that are necessary for the activity, even for an office one, are frequently much more important than the direct ones.

For example:

- it is necessary to heat the office, and that generates direct greenhouse gases emissions (if coal, fuel oil or natural gas are used) or indirect ones (if electricity is used,because of the above mentionned reason),

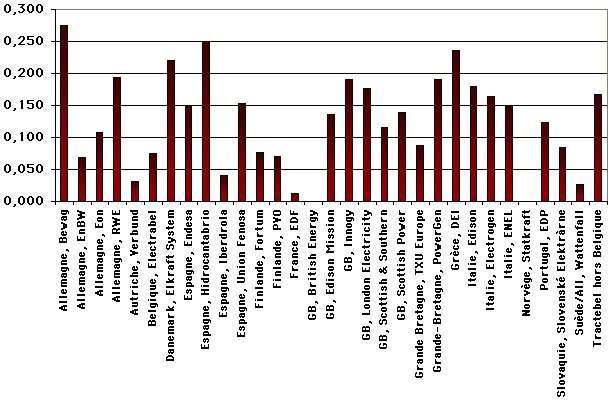

- any activity consumes electricity, that has to be generated ; however depending on the producer the emissions linked to electricity generation can widely vary,

CO2 emissions caused by electric generation, in kg carbon equivalent per electric kWh, depending on the producing company.

Source : ADEME, 2003

- The transportation means that are necessary, either for employees commuting and travel, or for goods delivery and shipping, all emit greenhouse gases (actually mainly CO2), because they mostly run on fossil fuels (even trains mostly run on fossil fuels if the electricity generation is mostly made with fossil fuels !),

- The premises used by the activity had to be built, hence raw materials had to be produced, transported, and assembled, and these processes (mostly raw material production) reuire significant fossil fuel consumptions, and therefore greenhouse gases emissions,

- As the case may be, some raw materials had to be produced to feed the activity, and this production generated greenhouse gases emissions,

- As the case may be, machines and tools had to be manifactured, and that also generated greenhouse gases emissions, to produce, transport then assemble the corresponding materials,

- there might be some leaks of the air con circuitry, that generally contains some potent greenhouse gases,

- waste, or packaging of the products sold, when landfilled or incinerated, generate greenhouse gases emissions….

As there is not a single company that does not use transportation means for the commuting of its employees, or never consumes any manufactured product, be it paper sheets, that lead to greenhouse gases emissions when produced, there is not a single company that doesn’t exert, directely or indirectely, a pressure on the future climate.

Any company or office activity (even not for profit) can therefore have a legitimate interest in the greenhouse gases emissions that it generates, directely or indirectely. As the place where the greenhouse gases emissions occur are of no importance, any decrease, be it on the direct emissions, or the indirect emissions, is a “profit” in the present case.

And, of course, it is not possible to establish priorities for action without measuring the respective contributions of the various sources of greenhouse gases, direct or indirect. Anyone can contribute, and it is only through measurement that it is possible to know where are the reduction possibilities, and what they consist of.

That is why I contributed to setting up, from mid-2000 to present, for the french energy and environment agency, ADEME, and the french Mission Interministérielle pour l’Effet de Serre, a methodology – and an associated tool – that allows to estimate both the direct and indirect emissions for any industrial or office activity, the “Carbon Inventory”. . This name designates both:

- a method to estimate the greenhouse gases emissions, compatible with the GHGprotocol initiative,

- an Excel worksheet ready to use to make the calculations, compare the emissions from one year to another, and evaluate the reduction potential of various possible actions,

- the worksheet user’s guide,

- the document describing the setting up of the tool, the general rules followed, the calculation of the default emission factors, and the sources used.

The general idea is to use easily accessible data in the entity examined, while still coming to an acceptable evaluation of the direct and indirect emissions.

General principle of the methodology

The basic idea of the methodology is to take into account all the physical flows that are necessary for your activity (flows of people, goods, energy) and to associate to them the greenhouse gases emissions they generate. However, most of the time, greenhouse gases emissions cannot be directely measured. What can be measured is the the atmospheric concentration of each greenhouse gas, but it is only exceptionnally that emissions can be directely measured.

Indeed, it would not be convenient to put a measuring device at the end of each tailpipe, each domestic boiler exhaust, or over each field…. It is thus necessary to proceed differently. The method consists in mixing calculations and observations.

Let’s take an example, regarding the combustion of natural gas, that can be used for heating or for industrial processes. Natural gas is mainly composed of methane, which has the chemical formula CH4, along with a little of other gaseous hydrocarbons and sulfur, the proportion of the latter varying depending on the origin of the gas.

But the gas operators know, for a given field, what is the exact composition of the gas, and even how it varies over time, hence what is the mass of carbon in a kg of gas. From this information, it is possible to know how much CO2 will the perfect combustion of a kg (or a cubic foot) of gas will produce. Then laboratory observations allow to correct a little the value, because any combustion is imperfect, and produces various trace gases, some of which are greenhouse gases, and other (typically sulfur dioxide) are aerosol precursors. The theoretical value is then “ameliorated” with exact lab measures, where true conditions of the use of the fuel are reproduced.

With these lab measures and the analysis of the gas that comes out from the various fields, we can calculate the average greenhouse gas emission (mostly CO2) that happens when burning a kg of natural gas.

This average greenhouse gas emission produced when burning a kg of gas will be called the emission factor of natural gas: each time we burn a kg of gas, we will assume that it is this average amount of greenhouse gases that will be released in the atmosphere, without bothering to check it with instrumental data. If we burn 25 kg of natural gas, we will just multiply this emission factor by 25. The whole interest of this way to proceed is of course that it is much more easier to know how much natural gas is burnt than to install an appropriate captor at the end of the chimney to measure the production of the various greenhouse gases, or to analyse in real time the exact composition of the gas burnt.

We will find this kind of approach everywhere in the “Carbon inventory”: for car trips, for example, it is possible to obtain average fuel consumptions per km for a given category of automobiles, and from there deduce average greenhouse gases emissions per km (with the appropriate emission factor for car fuel). This average value will then serve as an emission factor for the future trips with this category of cars, etc. The setting up of the tool therefore mainly consisted in calculating emissions factors for:

- Direct energy consumptions, be they known in litres, tonnes, kWh, or toe (tonnes oil equivalent). For example, for natural gas, the emission factor is 64 grams carbon equivalent par kWh “all included”: extraction from the gasfield, transportation, storage, distribution, and of course combustion.

- Transportation, whatever unit is available: number of trips per transportation means, passenger.km per transportation means, tonnes.km per transportation means, number of people commuting by car to the office…. For example, a tonne.km in an articulated truck generates 29 grams carbon equivalent on average,

- Nitrogen fertilizer use (that lead to N2O emissions), and leaks of fridge circuitry (that contain halocarbons). For example spreading a kg of nitrogen on a field generates, on average,1,4 kg of carbon equivalent worth of N2O,

- Raw material production. For example producing a tonne of steel out of iron ore generates 850 kg carbon equivalent of greenhouse gases,

- Direct waste arisings, depending on the waste management system (incinerator, landfill), which amounts known in tonnes. For example incinerating a kg of plastic without any heat use generates 0,8 kg carbon equivalent of greenhouse gases,

- Wastewater, provided their concentration in BOD is known (but this is a well known parameter). For example, 1 kg of BOD in the wastewater will, on average, generate 1,6 kg équivalent carbone of methane,

- emissions associated to the construction of the premises, expressed in kg carbon equivalent per m2 of office floor,

- etc.

How can the results be agregated ?

Once it is possible to associate emissions to the existence of any good, service, or energy flow that concurs to the activity, there still remains to know “where to stop” and how the results can be agregated, that is what sub-categories are appropriate to present the results in a meaningful way, and within what scope do the calculations take place.

Three possible scopes, that each correspond to a different approach, are “built in” in the worksheet, but the method allows to choose a different scope, as soon as it corresponds to a clear logic, and that the results are presented with an explicit recall of what was done.

1. In-company emissions inventory

One can decide to only take into account the emissions that take place “inside the company”, and only from static sources.

Though this approach will often leave aside the majority of the overall emissions associated with the production of a good or a service for the end user or the consumer, as we will easily see below, it allows to get more familiar with this particular accounting, and the implementation is extremely fast. Otherwise this scope is very close to the one that applies for the european directive on tradable permits, the only difference being that the european directive, for the time being, only deals with CO2, whereas the Carbon Inventory takes all greenhouse gases into account.

At last, the emission factors used in this scope, that only includes direct fossil fuel use, are derived from numerous international works, and allow a relatively precise reporting of the emissions.

In this “in-company” scope, the only sources taken into account are:

- direct combustion of fossil fuels (industrial processes or office heating),

- internal emissions not caused by combustion (evaporation and leaks, any chemical reactions other than combustion) that happen within the boundaries of the activity examined

Emissions linked to electricity generation are not taken into account in this scope, what can lead to side effects:

- if a company buys its electricity, the corresponding emissions are not included in the “in-company” scope, whatever way this electricity is generated,

- if the same company produces its electricity “on the spot” and uses coal, oil or gas to do so, then the corresponding emissions will be taken into account.

Let’s suppose that a company stops to buy coal generated electricty, which has the highest greenhouse gas content per kWh, to produce its own electricity with gas, that leads to emissions half as high (as coal) per kWh. If we look only inside the “in-company” scope, our company will increase its emissions, since it will have to take into account the emissions associated with the gas burning that did not exist previously, when abandonning coal generated electricity produced “outside” has no effect on this scope. Though substituting coal generated electricity for gas generated electricity, seen as a whole, leads to an emissions savings, the net effect on our company is an increase.

It is thus strongly advised never to investigate only within this scope to have a broad view of the situation.

2. “Intermediate emissions” inventory

We can decide to enlarge the scope and include emissions that correspond to part of the processes that happens outside, but that are necessary if we want the activity to exist under its present form. Why only a part ? The idea here was to design a notion that would be the equivalent of the “added value” in economy, that is “something” that can be summed up all along the chain of companies concurring to the production of a product or a service (excluding energy industries and transportation companies), while being sure not to forget anything without taking the same thing into account twice.

In this “intermediate emissions” approach, the following processes will be taken into account:

- direct combustion of fossil fuels (industrial processes or office heating),

- internal emissions not caused by combustion (evaporation and leaks, any chemical reactions other than combustion) that happen within the boundaries of the activity examined

- generation of the electricity and steam purchased (emissions that will thus occur within the internal boundaries of the power plants),

- trips of employees in the course of their work,

- home-office commuting of the employees,

- road, air or sea freight to the customers or, for a store, emissions arising from the transportation of the clients to the store (a significant source for suburb supermarkets, for example).

This approach is suited for future agregates: it is pretty easy to sum up the emissions obtained with this scope to get the emissions of a wider ensemble (a city, a group of companies, a vertically intergrated production chain, etc, as long as the ensemble does not inclure an energy industry or a transportation company. There is no possibility that the emissions corresponding to the above items can be counted twice while calculating the “intermediate emissions” of another company.

In addition, this scope allows to compare companies without wondering whether they posess their own transportation means or not, and without wondering whether they self-produce part of their electricity or not.

Here is a practical example of the possible use of this scope: to get the agregated emissions of chair manufacturing, hence the “average amount of greenhouse gases associated with the manufacturing of a chair”, all we have to do is sum up the intermediate emissions of the steel manufacturer (pro-rata the steel used, of course !), those of the plastic manufacturer, and so on for the other raw material producers that contribute, then the intermediate emissions of the company that “makes” the chairs from steel and plastic, then those of the retailer that will sell them. Doing this, we will have converted in greenhouse gases emissions all the physical flows associated with chair manufacturing without converting the same flow twice.

By dividing this total by the number of chair produced, we will get the “greenhouse gas content per chair”. This is one of the interesting information that will derive from the methodology once couting one’s emissions will become of common use.

But, as we will see below, for a given company the “intermediate approach” might still highlight only a small fraction of what is happening “elsewhere and is necessary for the activity.

3. Overall inventory

Finally, an activity may want to assess the overall pressure that it exerts on the environment in terms of greenhouse gases. If a company needs steel to make its products, that steel has to be manufactured. A company’s need for steel translates into emissions elsewhere, and these emissions can legitimately be imputed to the purchasing company. The company may eventually have the option of choosing another less “GHG-rich” material for its manufacturing process, or of reducing the amount of material used.

More generally, in the overall inventory any incoming or outgoing material or energy stream is accounted for, just as in financial bookkeeping the counterpart of any flow is wrtitten down.

In a balance sheet, indeed, everything that concerns a company is translated into figures, even if production occurs elsewhere. The purchase of a photocopier is entered, even if there is little chance that the machine was produced by your company, if it is a bank or a tool-and-die business.

Likewise, a company may want to inventory all GHG emissions that occur on the company’s behalf, even if they do not occur locally, but are linked to production of goods or services that the company uses.

Returning to the example of the photocopier, the manufacture of the photocopy machine causes GHG emissions. If the photocopier is ultimately used by your company, the corresponding emissions can reasonably be imputed to your company, just as depreciation or rental of the photocopier are entered in your company’s accounts.

This is the reasoning behind the “overall” perimeter, which includes all physical processes, wherever they are located, that enable your company to pursue its activity.

This approach aims to give the widest possible view of emissions, and to suggest the greatest number of steps for reducing them. You may realize, for example, that your in-company or intermediate emissions are minor in comparison to those due to the manufacture of the raw materials transformed or processed by your company.

You will then understand that, in order to lower overall emissions, it will be more useful to sharply cut purchases of materials, or stop buying materials that are heavy “polluters” in terms of GHG and replace them with other materials, rather than to make a big effort to immediately try to put any employee on a bicycle for home to work commuting.

For example, if your company makes garden furniture, you will realize that shifting from plastic to european wood (tropical wood might be associated to deforestation, so the result is unclear) will yield much greater gains than eventually cutting back a bit on the amount of plastic used.

In this “overall inventory” approach, the following processes will be taken into account:

- direct combustion of fossil fuels (industrial processes or office heating),

- internal emissions not caused by combustion (evaporation and leaks, any chemical reactions other than combustion) that happen within the boundaries of the activity examined

- generation of the electricity and steam purchased,

- trips of employees in the course of their work,

- home-office commuting of the employees,

- road, air or sea freight to the customers or, for a store, emissions arising from the transportation of the clients to the store,

- suppliers deliveries to your company’s premises,

- manufacture of products and materials incorporated into your company’s production (including materials for packaging),

- construction of the building(s) your company occupies, even if rented,

- manufacture/construction of machinery used,

- disposal of waste produced by your company, directly (waste in company rubbish bins) or indirectly (packaging used for your company’s products, that is destined to become waste).

This approach allows the broader vision on all the necessary processes on which action is possible (even transportation for suppliers’ deliveries: it is sometimes possible to choose a closer one, to change the unitary weight of the delivery…). It is necessary, still, to conclude by an important remark: we are only discussing greenhouse gases emissions here, and no other impact of your activity on the environment.

In a limited number of cases, minimizing GHG emissions may lead to increases in other pollutant emissions. One well-known example involves vehicle fuels. Eliminating catalytic converters (or even tailpipes altogether) would increase engine power, and hence save fuel, for an equivalent output of mechanical power. In other words, eliminating catalytic converters is a positive step in terms of GHG emissions, but increases other negative effects – local pollutants, and noise (if the tailpipe is removed).

It is therefore a good idea to keep in mind the limits of this exercise. However this sort of antagonistic outcome is not systematic, on the contrary; in many instances reducing GHG emissions will also afford other advantages (called associated dividends).

For example, shifting from car travel to train travel for passengers (or from plane to train) can yield significant emissions savings without negative or contradictory side effects, that is that there is no associated increase of another pollution.

4. Comparing the different scopes

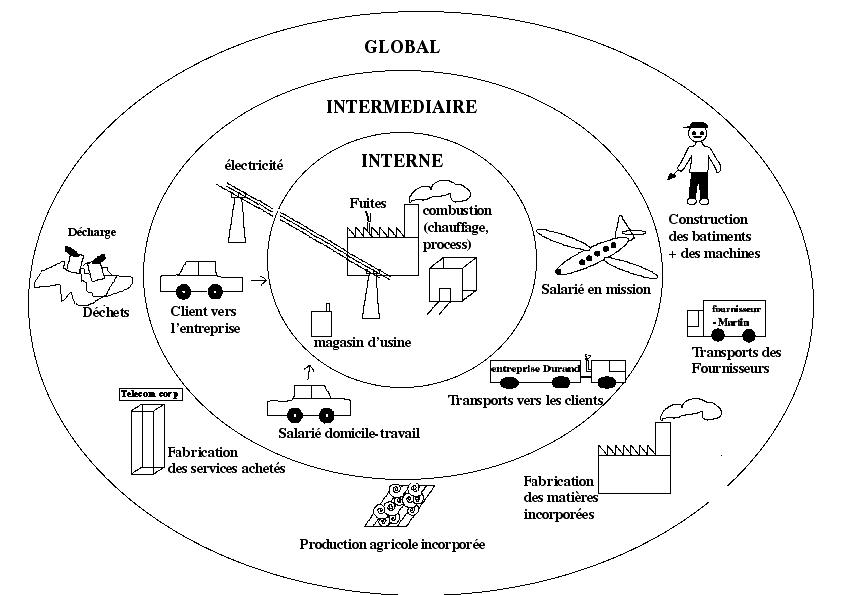

The graph below summarizes “visually” the different possible scopes.

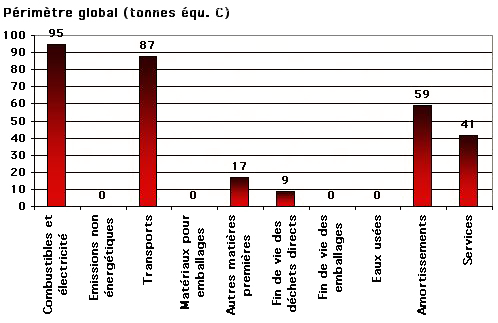

After the investigation is completed, we get a presentation of the emissions by subtotal that resembles this:

An example of the breakdown of the overall emissions of a manufacturing activity (2nd transformation), in tonnes carbon equivalent.

An example of the breakdown of the overall emissions of an office activity, in tonnes carbon equivalent.

What can be done with the results ?

1. Publish

The first thing that the company or office activity may want to do is to publish these figures, either in an environmental report, or in an in-house publication. This might correspond to an obligation, or a simple “demand” of the “civil society”, for whom the “environment report” is generally designed. Publishing such figures should not be restricted to industrial companies: let’s remember that every job in an office activity requires between 1 and 1,5 tonne oil equivalent of energy each year, which is just 30% to 40% more than the global energy consumption of an average French person in 1960.

Ideally, the presentation of the figures should resemble every aspect of what can be found in a financial report, which gives at the same time:

- the methods and rules,

- the quantitative values obtained,

- the changes in the methods used and their incidence on the acounting when figures are published on a regular basis (what is a good idea to assess the evolution).

Publishing such information might become useful, pretty soon, for customers that consider environment preservation as an important issue (and that might link their purchases to this aspect, particularly if it has an incidence on the costs !), investors (for ethical investment, or just wise guys that associate a high risk of cost increase to high greenhouse gases emissions), the state administration (voluntary reduction agreements), environmental defense associations, graduates that apply for jobs, and other stakeholders….

In France, a bill passed in may 2001 creates the obligation, for public companies, to publish information pertaining to the impact of their activities on the environment. It remains unclear who exactely should do what exactely, but the direction is clear, and more precise rules could be set up almost any moment. Better be ready, then !

Juste the same, the european directive on tradable permits, that will enter into force in january 2005, already compells many large industries to take a very close look at their emissions, and, just as for many other innovations, this “interest in greenhouse gases” will probably spread from there in the whole of economic activities.

Let’s also mention the sustainable development rating of companies, that might well start to include a “global climate footprint”, or the behaviour of banks, that might adapt their interest rates depending on the overall emissions, since the higher these emissions, the higher the risks on the medium and long run.

At last, public service office or tertiary activities are not forgotten (in France) : there is a clear instruction given to all state administrations to measure then reduce their greenhouse gases emissions. Even though it will probably not be fully applied, “something” will probably remain of this instruction.

2. Set up a voluntary action to reduce the global emissions

When a company has assessed its emissions, it will be able to establish – at least that is the idea ! – an action plan to voluntarily reduce its emissions.

Before doing so, however, it is strongly advised to assess the overall emissions at least once. Indeed, before considering any reduction whatsoever, it is indispensable to know where are the main sources of emissions in the whole production process of the product or service, because:

- better spend one’s time – that is not infinite – on an external source that is worth 100, rather than on an internal source which is worth 1,

- the important thing is to obtain the larger possible reduction, wherever it is, since the place of emission of greenhouse gases is of no importance for the future climate.

This methodology then allows to avoid a well known bias when just part of the processes are in the scope: somes unassessed emissions might increase as a result of the decrease of the sources that are assessed. Wishing the spreading of electric cars in a country that uses mostly coal produced electricity is typical of this biased conslusion we will come to if we just assess the direct emissions of transportation.

3. Include a reduction objective in a ISO14001 or EMAS environment management system

Assessing the greenhouse gases emissions, and seeking their reduction, will of course be possible (and even highly desirable !) in the course of the setting up of a environment management system, such as those concerned by the ISO 14001 or EMAS standards.

4. Ask the suppliers to do the same, and also commit to reductions (or change suppliers !)

Once the overall carbon inventory is done, part of the possible reductions will directly concern suppliers. It might be relevant to ask the suppliers to assess their greenhouse gases emissions, try (hard) to reduce them, and in he end it will even be possible to change suppliers to decrase the “greenhouse cost” of the production, just as decreasing the financial cost is often a reason to do the same (including the climate change problem into the economy does not include more “injustice” than what already exists in the name of the value of the share !).

In a way, changing suppliers to reduce one’s overall emissions is anticipating future savings when a “carbon tax” comes into force, what will probably eventually happen, or reducing the exposition to an increase – unavoidable in the long run – of fossil fuels.

5. Modelling and anticipating

5.1. Modelling

The method allows not only to calculate present emissions, but also to estimate what they would be in a different situation. For example, if a company changes supplier for its electricity, depending on the “carbon content” of the kWh for the new supplier and that for the old one, it will be easy to model how this will impact the overall emissions.

If a company decides to send its goods by train rather than by road, or by boat rather than by plane, or to replace aluminium by steel, or ammoniac rather than R22 for the air con, etc, it will be possible to evaluate the savings, both in absolute figures and relatively to the rest of the emissions.

5.2. Anticipating

The “carbon inventory” allows, once completed, to know where the cost increases would be if a carbon tax came into force.

For example, the company “Smith and sons” sells biscuits. It realizes that for every ton of biscuits sold, there is roughly one ton of carbon equivalent of greenhouse gases that go into the atmosphere, corresponding to :

- wheat culture (the main source in this process pertains to fertilizers, both for their manufacture and their use)

- gas use in the ovens of the company

- methane emitted by the paper packaging of the biscuits after it is landfilled,

- etc.

This means that if greenhouse gases are subject to a tax, let’s say 100 euros per tonne of carbon equivalent, the biscuits sold by Smith and sons will cost an extra 0,1 euro per kg. If the carbon tax jumps to 1 500 euros per tonne (what would lead to a doubling of the price of car gas in France), the biscuits sold by Smith and sons will cost an extra 1,5 euro per kg

We see on this example that the assessment of the “overall” emissions allows to quantify, in rough figures, the extra cost paid by the consumer if a carbon tax was to be set up. This methodology hence allows to anticipate.

A couple of practical examples

Exemple 1: A chemical plant

In the case of a company that makes chemical products, using the “In-company” emissions inventory perimeter, you will report :

- fuels used in production facilities,

- fossil fuels used to heat company premises,

- eventually emissions due to losses and leakage (gases, refrigerant fluids) and gases flared for purposes other than energy production.

But your company also uses electricity, its employees travel to work, sales staff visit customers and products are shipped. To obtain an “Intermediate emissions” inventory the following are added:

- emissions linked to generation of the purchased electricity or steam

- home-to-work travel by employees

- emissions due to employee travel in the course of their work

- transport for delivery of merchandise to customers.

Lastly, you may want to consider the following:

- production of raw or primary materials used by your company causes emissions, and these should be reported

- transport of these products to your company’s premises causes emissions, that should be reported

- your company’s waste (whether incinerated or landfilled) causes emissions that should be reported

- the products and services purchased by your company (telecommunications, machinery, buildings, office equipment) also cause emissions when they are produced, and should be reported

- etc.

Hence the Overall carbon inventory adds in:

- emissions linked to manufacture of basic products

- emissions linked to construction of your company’s buildings and machinery

- emissions linked to transport of supplies to your company’s premises

- emissions related to end-of-life treatment of waste and discarded material.

Example 2 – Finishing trades in building construction

Suppose now that your company installs windows (bought outside). It therefore has no industrial process. Under the In-company emissions inventory you will report:

- natural gas or fuel oil for heating company premises

- solvent fumes emitted during certain gluing operations, etc.

In addition, employees come to work, then take vehicles to work sites, while the boss visits customers, and some electricity is consumed as well. To obtain an Intermediate emissions inventory the following are added:

- emissions linked to generation of the electrical power the company purchases

- fuel used by work-site vehicles

- home-to-work travel by employees,

- emissions during travel by the owner, even if s/he uses his/her own vehicle(s).

Lastly, you may want to consider the following:

- the aluminium and plastic frames, and the glass in the windows your company installs were produced using energy, hence with greenhouse gases emissions, and this should be reported

- transport of these frames and glass to your company’s premises causes emissions, that should be reported

- your company’s waste (scraps of construction materials, paper etc.) whether burned in an incinerator or sent to landfill, causes emissions that should be reported

- the products and services purchased by your company (telecommunications, machinery, buildings, office equipment) also cause emissions when they are produced, and should be reported

- etc.

Hence the Overall carbon inventory adds in:

- emissions linked to manufacture of the windows your company installs

- emissions linked to transport of these windows from the manufacturer to your company’s premises

- emissions linked to construction of your company’s offices, workshops and tools

- emissions linked to incineration of plastic scrap

- emissions related to landfilling of a portion of your company’s waste (paper for example).

Example 3 – A hardware and “do-it-yourself” store

Suppose now your company is a mass-distribution “do-it-yourself” retail store located in the suburbs. The In-company emissions inventory will cover only:

- all direct fuel consumption for heating

- all leakage of refrigerant fluid from air-conditioning systems (if any).

The Intermediate emissions inventory will also include:

- emissions linked to generation of the electrical power the company purchases

- fuel consumption for company vehicles

- home-to-work travel by employees

- travel by customers to the company’s retail stores

- work-related travel by employees using their own cars.

The Overall carbon inventory will include, in addition:

- emissions that occur during manufacture of products sold by the reporting company

- emissions related to manufacture and end-of-life treatment of items destined to become waste (packaging of products sold)

- emissions related to end-of-life treatment of waste directly discarded by the retailer

- emissions linked to transport of manufacturers’ products to the retailer’s premises

- emissions linked to construction of the retailer’s buildings and machinery

- emissions linked to manufacture of office and computer equipment used

- emissions incorporated in purchased products or services (for example, paper used for advertising flyers distributed in letter boxes, etc.).

With this example it is easy to see that there will be a major difference between the In-company emissions inventory and the Overall carbon inventory: emissions induced by the reporting company’s activity but not generated directly on-site will be preponderant over those that occur locally.

Example 4 – A bank

Suppose your company is a bank branch office: for the In-company emissions inventory you will take into account

- fuel(s) used for heating (fuel oil or natural gas, or coal as the case may be)

- leakage of refrigerant fluid from the air-conditioning system (if any).

The Intermediate emissions inventory will also include:

- emissions linked to generation of the electrical power the office uses

- work-related travel by staff

- home-to-work travel by employees

- travel by customers to the branch office.

For the Overall carbon inventory the following are added:

- emissions linked to manufacture of office supplies, notably paper

- emissions linked to manufacture of office and computer equipment used

- emissions linked to construction of the building occupied

- postal services for mail (including junk mail !) to customers, etc.

Example 5 – Regional government offices

Suppose the reporting entity is a government office: this tool is by all means applicable to public agencies.

For the In-company emissions inventory you will take into account:

- fuel(s) used for heating (fuel oil or natural gas, or coal as the case may be)

- leakage of refrigerant fluid from the air-conditioning system (if any).

Then, for the Intermediate emissions inventory:

- emissions linked to generation of the electrical power the company uses

- work-related travel by staff

- home-to-work travel by employees

- travel by users to the premises designated for receiving the public.

For the Overall carbon inventory the following are added:

- emissions linked to manufacture and end-of-life treatment of office supplies, notably paper (even if it is archived)

- emissions linked to manufacture of office and computer equipment used

- emissions linked to construction of the building occupied

- postal services for mail to constituents, users, etc.