The general press seldom quantifies the impact of “politically correct” individual actions regarding the fight against climate change : how much is saved if you throw away a classical light bulb for a low consumption one, and what does it represent compared to the ultimate reduction we should achieve ? I therefore found interesting to suggest my own hierarchy, based on a couple of rough figures easy to calculate. I ranked the various actions by increasing difficulty to “get started”.

For each action I indicated the benefits regarding climate with a number of crosses (+ to ++++) and the financial impact with dollar signs ($$$ to $$$ ; red when it represents an extra cost for the consumer, green when it induces a saving, when nothing is indicated it means that the financial impact is null or not calculable).

Some important things that the reader should keep in mind:

- in France the electricity generation is mostly CO2 free (80% nuclear and 15 hydroelectric). Therefore savings on electricity have a much lower impact on CO2 emissions than savings on direct combustion of fossil fuels. This is not at all the case in most european countries, and even less in the USA, where electricity savings will mean important CO2 savings

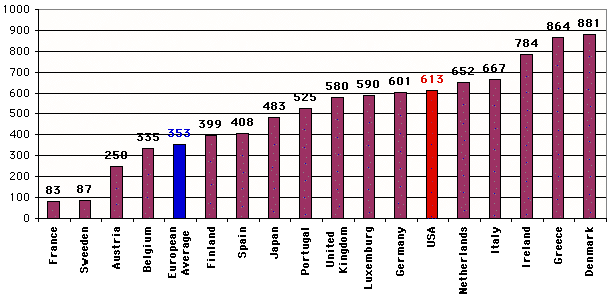

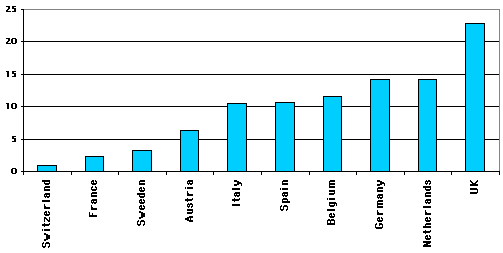

Number of grams of CO2 freed in the atmosphere for the production of one kWh of electricity in 2001, for the various countries of the EC, USA and Japan.

France emits “only” 83 grams of CO2 – in average – to put 1 kWh on the grid, when Denmark or Greece must emit nearly one kg of CO2 to get to the same result.

Therefore the suggested hierarchy that follows is only applicable to France, or to Switzerland (not shown on the figure, but that is at the same level than France for electricity generation) and Sweeden (these 3 countries produce most of their electricity with nuclear plants and dams). For any other country, an important electricity saving will be synonymous of an important saving on CO2 emissions.

- a Frenchmen emits roughly 2,2 tonnes carbon equivalent per year, all greenhouse gases agregated and sinks deducted from the raw emissions.

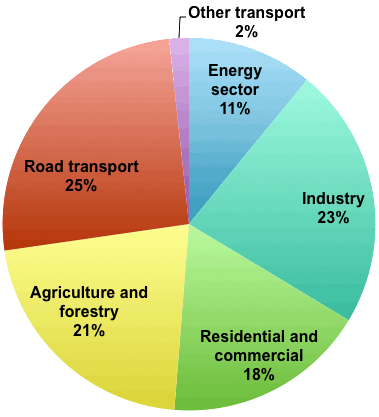

- And at last it is useful to keep in mind the breakdown by sector of greenhouse gases emissions in France (below).

Breakdown by sector of the greenhouse gas emissions in France in 2001.

NB: international air or sea transportation is not included in the figures.

Source : CITEPA, 2012

For the french case, I did not mention the savings that are almost negligible, for example……low consumption light bulbs.

And at last one will easily realize that saving CO2 emissions generally means :

- saving energy,

- saving money ! In addition, if the price of hydrocarbons suddently rises, what is very probable “one day”, the less we consume and the less we suffer…

Very easy

In the winter, lower the temperature by 1°C in any heated place ++ $

If one uses 2.000 liters (that is 520 US gallons, roughly) of fuel oil to heat a house during the winter, the corresponding CO2 emission is 1,25 tonne carbon equivalent. If natural gas is used, for the same energy spending, the CO2 emission still amounts to 1 tonne carbon equivalent

If the inner temperature is 1°C lower, the saving can amount to 10% of the energy spending for heating (the average value is more around 7%). If one uses 2.000 liters of fuel oil during the winter (average value for a small european house), a 10% saving represents 125 kg carbon equivalent (5% of the global emission of a French). If fuel oil costs 0,5 euro per liter, a 10% saving in this case generates an economy of 100 euros.

Avoid using the air con in cars ++ $

When using air con in a car, the consumption can increase by 20%.

If one drives 15.000 km per year in urban trafic, and if one third is done using the air con of the car, not using it represents a saving of 100 to 200 kg carbon equivalent per year (for a european car, probably 50% more to twice as much for an american car)

Avoid watching ads on TV (and most of all prevent kids from watching them !) + to +++ / $ to $$$

If we ad up the emissions of industrial processes, services, transportation of goods and heating of commercial buildings (in short all that is necessary to produce the goods and services that we buy) we get, in France, 50% of the total emissions of the country

The less one consumes manufactured goods or energy intensive services (such as transportation services), and the more “vertuous” one is regarding greenhouse gases emissions. Well, consuming less is probably easier if one is not influenced by advertising (that is particularly true for kids and teenagers).

Easy

Thinking about the possibilities to move around before moving house ++++ $$

Driving 15.000 km per year in urban cycle generates at least 1 tonne carbon equivalent in a very small european car ; twice that amount in very large car or a SUV.

Transportation has become the first source of CO2 emissions in France (35 to 40% the total CO2 emissions, including the associated emissions of refineries, but excluding all the emissions associated to the manufacturing of cars), and is probably either the first or the second ranking item in most occidental countries. But transportation is also something that ranks first or second in the spendings of an average French. When moving house, avoiding to go to a new place that is badly served by public transportation is being virtuous twice:

- driving less has a strong impact to lower one’s greenhouse gases emissions (see below),

- investing less in a car is beneficial for the bank acount ! Furthermore driving can only cost more and more on the long term, as fossil fuels are subject to depletion (and biofuels have a very low potential). Avoiding to be totally dependant on cars in the new house is therefore a kind of wise insurance…

Eating as little meat as possible, and, among the meats you eat, as little beef as possible ++++ $$

Agriculture is responsible of 25% of the greenhouse gases emissions in France, more than industrial processes, and this essentially results – directly or indirectly – from cattle raising.

If we take all the peripheric processes into account (food processing, transportation, cooking, packaging manufacturing, etc) the simple fact of eating generates almost a third of the french greenhouse gases emissions.

Producing a kg of red meat generates 50 to 100 more emissions than producing a kg of cereals !

Eating a lot of meat requires the existence of an intensive agriculture (because it is necessary to grow a lot of plants to feed the animals !), which consumes directly or indirectly fossil fuels (for the manufacturing of fertilizers and pesticides, and operating the tractor), therefore leading to CO2 emissions, and generates also emissions of other greenhouse gases: when decaying, nitrogenous fertilizers cause N2O emissions, 300 times more “powerful” than CO2, and ruminants emit methane, which is 23 times more “powerful” than CO2, because of the fermentation of the plants they eat in their digestive sysem.

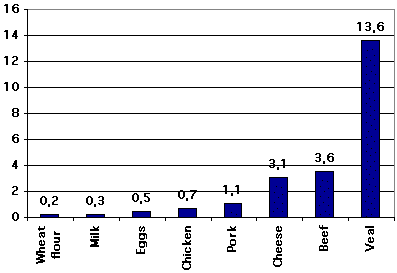

As a result of all this producing a kg of beef (with bones) leads to the emission of 3 to 4 kg of carbon equivalent. A kg of poultry “costs” only 0,5 to 1 kg carbone equivalent and pork a little over 1. All these figures are for non processed foods (otherwise it is necessary to add the emissions induced by the processing).

Carbon content of a selection of foods, in kg carbon equivalent per kg of food (non processed).

Source : Jancovici, Demichelis, 2003

Avoiding 2 steacks per week (that is 300 g per week) represents a 50 kg carbon equivalent saving at the end of the year.

All what preceeds remains valid, in a lesser way, for all that comes from cattle: veal (over 10 kg carbon equivalent per kg), milk and dairy products, ice-creams, butter, etc…

Without becoming vegetarian (!), it is rather easy (I’ve done it) to divide one’s consumption of meat and dairy products by 2, what, in addition to providing important benefits for greenhouse gases emissions, also allows some associated dividends:

- lesser pressure on water resources (it is necessary to use 500 liters of water to produce 1 kg of potatoes, but 20,000 to 100,000 liters to produce 1 kg of beef with cereals coming from irrigated cultures),

- a better health, mostly if the diminution primarily concerns “fatty” products (fat beef meat like steak, butter, ice-creams, etc)

- diminution of the use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers, as the necessity of a very productive agriculture (that, once again, is mostly necessary to feed cattle) disappears,

- freeing of land surfaces for other uses (wood production, or energetic cultures).

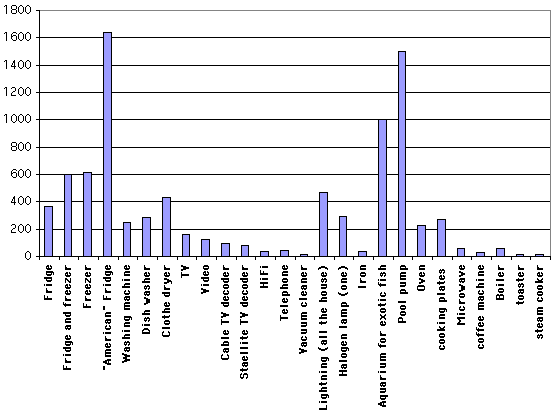

Choosing low consuming household appliances, and avoiding devices that are not really indispensable +/+++ $

In Germany, UK, or the US consuming 1000 kWh of electricity leads to the emission of 0,6 tonne carbon equivalent

Average measured electric consumption in France of various electric devices, in kWh per year (probably applicable to any european countries, given that manufacturers are european at least).

Source : Olivier Sidler, 2003

An average electric dryer (for clothes) consumes 400 kWh per year (when clothes generally dry if just hung somewhere…) ; an average fridge consumes 400 kWh per year but what we call an “american” fridge (with an ice machine) consumes, on average, 1600 kWh per year: 0,8 tonne of extra carbon equivalent just to have ice all year round !!

Being as sober as possible regarding the equipment of the basement and the kitchen will lead to significant savings. Unfortunately I don’t have the figures for air con, but I would bet they are rather high: not using air con in one’s house is probably a very significant act regarding greenhouse gases emissions.

Buying a car with no air con + $

the gases used as frigorific fluids in the air con (PFC, HCFC) are very potent greenhouse gases (several thousand times more potent than CO2) that always leak a little (leaks after several years are supposed to represent 33% of the initial load) and that are not collected when then air con is thrown away.

The emissions resulting from these leaks are additionnal to the emissions resulting from the extra fuel consumption of the car.

Avoiding to buy a car with air con therefore allows a double saving:

- while driving, on the fuel consumption,

- when the car is discarded, on halocarbons emissions.

Buying a small car +++ $$

If driving 15.000 km per year in urban trafic, one emits around 1 tonne carbon equivalent with a small subcompact car (e. g. a Smart, or a Twingo) but up to 2 tonnes with a large car or a SUV (average value, for specific vehicles it can go well above).

Between a small car and an SUV the consumption ratio can represent 1 to 5, depending on the conditions of trafic and the type of circuit (trafic jams and frequent accelerations are fatal to sobriety).

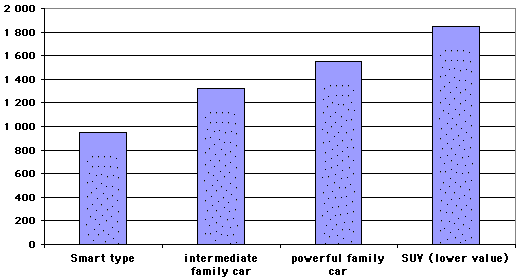

CO2 emissions (in kg carbon equivalent) corresponding to 15.000 km in urban trafic for various types of vehicles.

Emissions are linked to the manufacturing of the car and petrol refining included.

The SUV value is based on 15 miles to the US gallon, roughly.

Source : Jancovici/ADEME, 2003

If doing without a car is really not possible, just changing it for the smallest possible one (even if it supposes that part of the family rides by train when going on holidays) may lead to considerable savings on CO2 emissions: with15.000 km per year (average distance covered annually by cars in France) the difference between a small and large car is around 1 tonne carbone equivalent per year !

In addition, transportation being the first or second item in the spendings of an average French, having a small car has a significant impact on the content of the purse !

Buying a hybrid car ++ $$

if driving 15.000 km per year in urban trafic, switching to a hybrid car can save 30 to 50% of the fuel consumption, that is 0,5 tonne carbon equivalent at least.

Hybrid cars have an engine which is more efficient than that of “classical” cars”, and among other innovations they convert kinetic energy into electricity while braking. Such a vehicle needs 30 to 50% less gas than a “normal” car. On the grounds of 15.000 km per year, it allows to save 700 to 1.000 liters of gas (roughly 200 to 250 gallons) par year, that is around 500 kg carbon equivalent.

On the other hand buying an electric car is not necessarily a good way to save greenhouse gases emissions: it all depends on the way to produce electricity ! In France, it will yield a benefit, but in most other countries it will be even with petrol cars, or worse, because 66% of electricity in the world is produced with coal or gas fired power plants, that produce CO2 emissions.

Medium difficulty

Not flying +++ $

a plane roughly represents as many small cars as there are passenger seats (even empty). A person flying emits about the same as if he (she) was driving the same distance alone in a small car.

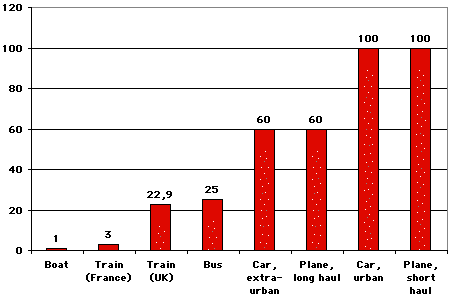

Greenhouse gases emissions in grams carbon equivalent per km done, depending on the transportation mode. Car values are for european automobiles.

Source : Jancovici, 2001

In France, a return trip from Paris to Marseilles corresponds to 150 kg carbon equivalent (all greenhouse gases taken into account, including water vapour injected in the stratosphere), when only 3 kgs are emitted for the same trip by train.

A return trip from Paris to New York corresponds to 900 kg carbon equivalent in average (much more in business or first class), that is one third of the annual emission of a French person all greenhouse gases taken into account. Flying three times to New York from Paris in a year is therefore equivalent to the whole annual emission of a French person.

Being “virtuous” regarding greenhouse gases is therefore not compatible with flying to the caribbeans in the winter (from Europe), organizing international meetings all the time, or occupying one’s retirement time with trips all around the world (it’s sad, but that’s reality !).

Not buying american products ++++

Emissions per person in the US are twice what they are in Europe. This will also be the case for emissions GNP unit, even with the difference of productivity between USA and Europe.

This is the consequence of an energy efficiency much lower in the USA for almost anything : industrial processes, building heating (houses are not well insulated), electricity generation is much more “carbon intensive” because of coal (see chart on top of this page), transportation (larger engines, more planes), etc.

Here’s something which is not at all politically correct, but so be it ! Figures are what they are…. The american economy being twice as intensive in greenhouse gases than the european economy, and almost threefold compared to France, it means that each time one buys a product manufactured in the US instead of a product manufactured in Europe, one doubles the emissions corresponding to the production of the given good or service.

Buying european in general (and french, swiss or sweedish in particular !) is a very good start to fight against climate change.

In addition, the US being much more sensible to the good steadiness of their exports than to loud protests of political leaders in international meetings, “acting with one’s wallet” is probably much more efficient than anything else to exert a pressure on the politicial orientations of their leaders (criticizing them in the paper probably doesn’t bother them much as long as we go on buying their computers and visiting Disneyland).

This means that a good start for fighting against climate change includes (but the list is much longer…):

- invest at the Paris stock market rather than at Wall Street,

- visit Austria or Italy (by train, of course !) rather than Boulder (Colorado),

- see “The Full Monty” rather than the latest Bruce Willis,

- buy Adidas rather than Nike,

- avoid renewing one’s computer too often,

- and basically carfully look at the “made in” on the labels !

Lowering as much as possible the temperature in homes +++ $$

If one consumes 2.000 liters (roughly 520 US gallons) of fuel oil in the winter,saving 30% represents 0,5 tonne carbon equivalent.

By lowering the inner temperature by a couple degrees, (from 22 to 19 °C for example), it is possible to save up to 30 or 40% on the emissions corresponding to heating. Manufacturing sweaters and blankets is negligible compared to the savings on heating !

Organizing car-sharing to commute to work + $

5.000 km per year (which corresponds to a distance between house and work of 10 km) in a subcompact car leads to an emission of 0,35 tonne carbon equivalent. By increasing the number of passengers, the individual emission can be divided by the corresponding figure.

If the return trip to work is 30 km long (20 miles roughly) the corresponding emission is close to 450 kg carbon equivalent (european cars), and therefore the economy is of 0,2 tonne carbon equivalent per person for a sharing at two, and 0,3 tonne for a sharing at three.

Insulating one’s house the best possible way +++ $

If one consumes 2.000 liters (roughly 520 US gallons) of fuel oil in the winter,saving 50% represents 0,8 tonne carbon equivalent.

A good thermal insulation allows an important decrease of the emissions linked to heating. Between a well insulated house, and one that has holes everywhere, the energy spending – and therefore the emissions, if the energy used is the same – can go from simple to double with a constant inner temperature. If in addition the thermostat is put at the lowest possible value (19 °C for example) the consumption can be cut by as much as 70% (an engineer specialized in energy savings that I know boasts 90% with a combination of solar heating, insulation, and temperature regulation).

With 2000 liters of fuel oil that leads to 0,8 tonne carbon equivalent per year.

Buying as much products as possible from open markets and little local retailers ++ $/$

Going to local stores divides by two the energy spending linked to shopping.

A study of the french institute INRETS showed that, for the same turnover, hypermarkets in the suburbs generated an emission twice more important than intown small supermarkets (and the turnover of hypermarkets has a “job content” twice lower ; in other words the creation of one job in a large suburb hypermarket “kills” two jobs among local retailers). Other studies that I heard of are qualitatively consistent.

This “virtue” of local retailers is basically the consequence of shorter trips to go shopping: customers don’t need to to a long trip when going to the local store, and part of the trips is done on feet (well at least in european cities…), when hypermarkets require a car no matter what.

As buying local diminishes the transportation spending, it is difficult to say what is the net result in financial terms. If buying local avoids to have a second car, the financiel gain is obvious. If it avoids to buy all unecessary stuff at the hypermarket (and some mothers can probably testify that the list can be long…) the financial gain may also be potentially important.

Not ordering overnight deliveries + $

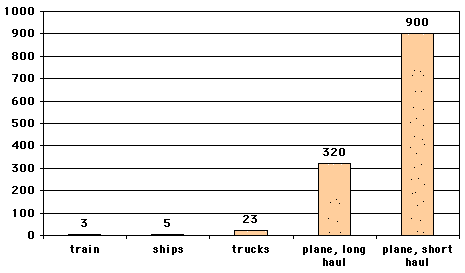

moving 1 tonne of goods over 1.000 km corresponds to an emission of almost 1.000 kg carbon if it is transported by plane (short haul), 25 kg by an european large truck, and 3 km in a french train , r, 25 kg en gros camion, 3 kg en train.

Greenhouse gases emissions by tonne.km depending on the transportation means.

Source : Jancovici/ADEME, 2003

Wishing a fast delivery requires the use of planes for long distances (trains don’t go as fast) and the use of trucks only for shorter ones (handling goods when using trains requires time, apart from the fact that everybody does not live off a train station).

The objective of having logistics chains as short as possible has a strong share in the soaring of the number of trucks worldwide ; in the US, where the trend started earlier than in France truck sales jumped from 2,5 millions to 7,2 millions per year from 1980 to 1997 !! (Data from Comité Français des Constructeurs d’Automobiles)

Drinking tap water + $

That avoids to manufacture then throw away plastic bottles and to transport water by truck instead of transporting it in a pipe (much more efficient).

Eating season products, grown locally ++ $

Eating cherries in winter, tomatoes in March, New Zealand lamb or magoes all year round (in Europe, where it is not specially a local product), induces a quadruple energy spending that leads to greenhouse gases emissions:

- out of season fruits or vegetables such as strawberries or tomatoes in winter are cultivated in heated greenhouses, and heating is often done with fuel oil,

- transportation over a long distance for that is grown or raised far away,

- some goods travel frozen, well freezing units generally leak a little, letting go halocarbons (refrigerating fluids) that are extremely potent greenhouse gases, in addition to the fact that freezing goods require energy,

- a large fraction of what comes from remote places is (over)packed (more than in-season tomatoes bought from the local farmer at the local open market), what requires energy for producing the packaging then generates additionnal emissions when the packaging is thrown away.

Difficult

Taking public transportation to commute to work ++/+++ $$$

6.000 km per year (what corresponds to a return trip to work of roughly 30 km) in a european car generates roughly 0,5 tonne carbon equivalent.

If the trip is made using public transportation, the benefit varies from almost the above figure (switching from car to metro in France) to 2/3rds of the above figure (switching from car to bus, or from car to train in most european countries.

If this allows to avoid a second car in the household there will be induced savings for other trips, not mentionning a financial gain of 2000 to 3000 euros per year (public transportation generally costs half of what a car costs when being driven alone).

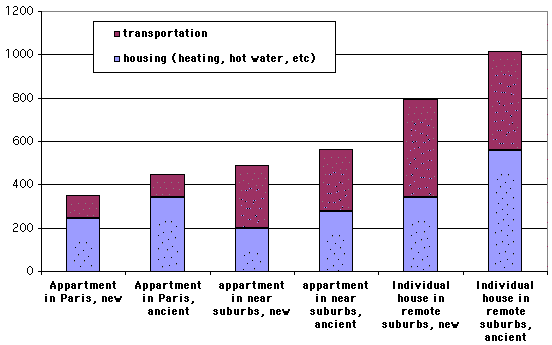

Living in a flat when living in a city (even a small one) ++++ $$

For the same living space, appartments require less heating energy than individual homes (up to half only)., beause the surface in contact with the outside is proportionnally smaller (the rest is in contact with another flat, generally also heated). They are also, in general, located in dense urban zones, therefore close to many services (shops, jobs, etc) that become accessible without using a car (in Paris, 1 person out of 2 doesn’t drive).

Annual greenhouse gases emissions per person, in kg carbon equivalent, for the agregate of housing plus transportation, for three zones in or around Paris.

“New” and “ancient” refer to the construction period of the housing: ancient is before 1974, new is after.

Source : Jancovici, on data from J.-P. Traisnel, les cahiers du CLIP, april 2001

One should note that, at least in France, living in the suburbs does not necessarily allows to save money on the total “housing plus non avoidable transportation” : most certainly housing costs less (in the suburbs), but people there spend more on thansportation, because they can’t use public transportation and travel more important distances (see below).

| Zone | Hyper-centre | Centre | Near suburbs | Remote suburbs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average income of the household (euros) | 3.156 | 2.951 | 3.005 | 2.647 |

| Tenants : housing + transportation budget of the household | 1.041 | 1.033 | 1.202 | 1.191 |

| Owners : housing + transportation budget of the household (mortage included) | NS | 1.092 | 1.382 | 1.403 |

Incomes and housing + transportation budgets depending on the residence zone.

Source : INRETS, 1998

In short, living in the suburbs means driving more and the available income after deduction of housing and transportation is about the same as what it is downtown. Most certainly downtown is not such a pleasant place to be in an american city, but in Europe it’s not exactely the same !

Leaving one’s car in the garage and taking the train for medium trips ++ $

1.000 km in car in extra urban cycle generates 60 kg carbon equivalent, in a french train only 3 kg carbon equivalen

The net benefit of substituting road by rail is around 200 grams of CO2 (that is 57grams carbon equivalent) per km. On a return trip of 500 km in total (for example going from Paris to Lille) the saving amounts to almost 30 kg carbon equivalent. If such a trip is done 10 to 20 times per year (week ends, visiting family, etc) the total at the end of the year is 0,25 to 0,5 tonne carbon equivalent.

With variable amounts depending on the country, switching from car to train remains a “good deed” in any place in Europe (and elsewhere also !).

Greenhouse gases emissions in grams carbon equivalent per passenger.km (that is one person traveling one km), in train, depending on the country. Reminder: traveling one km alone in a car generates 65 grams carbon equivgalent (in Europe).

The differences among the countries come from the various ways to produce electricity, the various proportions of trains running on fuel oil, and the different loading performance (swiss trains are among the most full in Europe).

Source : INFRAS, 1998

What about financial aspects ? Well, if we calculate the “whole cost” of driving, including not only the cost of fuel, but also the money spent to buy the car, insurance, highway fares, etc (which is the normal way to proceed), travelling by train costs much less than travelling alone in a car, and even for a couple the train will often be cheaper (in France at least).

Walking or cycling for small trips ++ $

As soon as the trip is less than 5 to 10 km (depending on your motivation and the time you have !) one can :

- use rollers or a bike if one doesn’t need to carry anything,

- buy a carriage otherwise…

Switching from fuel to natural gas for heating ++ $

For the same energy, natural gas is 25% less emitting than fuel oil. For someone that would use 2.000 liters (520 US gallons) of fuel oil in the winter, such a substitution would allow a saving of 0,25 tonne carbone equivalent.

The lower emission per energy unit of natural gas is linked to the fact that molecules of methane (the main component of natural gas) have the highest possible ratio of hydrogen on carbon. When burning, only carbon produces CO2, hydrogen produces only water.

Let’s note, though, that such a substitution can only be transient: natural gas is no more eternal than oil ! Hence we have here only a short term adaptation margin.

Installing a solar water heater +++ $ ?

An average household emits half a tonne carbon equivalent for hot water. A solar water heater allows to divide these emissions by two in the majority of cases.

A solar heating hence allows to divide the bill by two, even in northern places. The easiest installation concerns sanitary hot water. To convert to solar heating, heavy plumbing is necessary (the floor must be adapted, also).

A photovoltaïc panel allows to save on electricity, but is rather exepensive, and the impact on saving (for greenhouse gases) is limited by the fact that the manufacturing of this panel is very energy intensive. In addition, if the electricity is generated with a large part of “CO2 free” production means, as in France, the benefit will be null or negative.

Buy the least possible amount of products with a packaging +

Producing 1 kg of steel or a kg of glass generates 500 g to 1 kg carbone equivalent, producing 1 kg of aluminium (from bauxite) generates 3 to 5 kg of carbon equivalent.

Producing plastics, glass, cardboard, steel or aluminium, etc, consumes a lot of energy: in France, for example, 4/5th of the total energy used by industrial processes corresponds to the production of basic materials (metals, glass, plastics and basic chemical products, etc).

Any time one buys loose goods and hence avoids to buy a packaging, one generates de facto a saving of the emissions corresponding to the production of the materials.

One will notice that avoiding to buy products in supermarkets (where they are already packed, and often over-packed) buy rather buy them in open markets often allows to get to the same result (less packaging) as a by-product.

Buying the least possible quantity of manufactured goods ++++ $$$

A kg of manufactured goods “contains” from several hundred grams to several kg carbon equivalent (and probably more for very expensive products). For example, a car weighting 1 tonne “contains” 1,5 to 2 tonnes carbone equivalent (meaning that 2 tonnes carbon equivalent were sent in the atmosphere for its production, even if it is never used after), a computer “contains” several tenths kg carbon equivalent, etc.

As soon as we don’t buy a manufactured good, we save the energy that was necessary for its production.

One can start by not buying things that will be used once a year at most or that are not really necessary, but to “go further” the ideal situation is also to reduce one’s concumption of “normal” manifactured goods: cars, computers, toys, clothes, etc.

This means, alas for industries, that in the present context the least factories produce and the most virtuous we are for greenhouse gases: economic growth “makes” greenhouse effect. This also means that, as consumers, we bear a resposibility that we can’t ignore : we can’t at the same time ask to our elected representatives to reduce the greenhouse gases emissions and wish for ourselves the growth of our individual consumptions.

This is also valid for services : apart from flying (see above), do you know, for example, that a phone bill of 150 euros “contains” at least 4 kg carbon equivalent ?

Not having a dog (especially in urban areas) + $

Having a dog generally means:

- the consumption of meat products, well cattle raising is a major source of greenhouse gases (see above)

- a bigger car to go on holidays (because the dog must fit in), and therefore an increased daily consumption,

- more generally speaking a certain number of fittings or services that require energy.

Very difficult

Moving house to move around less +++ $$$

Becoming a home worker ++++

In certain conditions (working at home full time, without having an office elsewhere, without increasing the driving for non professionnal motives, and without flying more, it is possible to save up to 50% of the annual emissions of an average citizen (in France)

Dumping the car for good +++ $$$

For the same distance, a car emits 30 times more greenhouse gases tran a french train (and still 3 times more than an english train), and an european car requires 40 times more energy than a bicycle to go forward.

And what about the state ?

It is possible to find elsewhere on this website a couple of reflexions on the way the state can concur to a decrease of greenhouse gases emissions (but the political power is far from being able to do all the job alone).